There is a lot of misinformation out there regarding how the foot initially contacts the ground during running. For example, some people like to refer to themselves as “supinators,” as if it’s a diagnosis of something unique and bad. Some think that a midfoot landing involves the entire bottom of the foot contacting the ground at the same time.The reality is that we almost always make initial contact somewhere on the outside margin of the foot with the foot in a supinated position. I don’t think I have ever seen a runner not do this in all of the videos I have, and thus a midfoot strike does not equal a flat foot strike, and we are all in fact “supinators.”

There is a lot of misinformation out there regarding how the foot initially contacts the ground during running. For example, some people like to refer to themselves as “supinators,” as if it’s a diagnosis of something unique and bad. Some think that a midfoot landing involves the entire bottom of the foot contacting the ground at the same time.The reality is that we almost always make initial contact somewhere on the outside margin of the foot with the foot in a supinated position. I don’t think I have ever seen a runner not do this in all of the videos I have, and thus a midfoot strike does not equal a flat foot strike, and we are all in fact “supinators.”

After initial contact along the outside margin, the foot everts and rolls inward (what we commonly refer to as pronation). The amount of intial supination, the speed with which the foot pronates, and the amount that it pronates are largely what differ between runners.

To illustrate the initial contact point, I want to direct you to three great videos from Daniel Lieberman’s lab at Harvard. These videos are part of the supplementary information from his 2010 study in Nature and provide underfoot pressure tracings from barefoot runners exhibiting forefoot, midfoot, and rearfoot strikes. Watch how pressure migrates from outside to inside in all three – in no case is there any pressure under the ball behind the big toe at initial contact. I’ve had some trouble getting the videos to play in my browser, so if that doesn’t work you can right-click and save them to watch them on your computer.

Video 1: Pressure Tracing – Forefoot Strike

Video 2: Pressure Tracing – Midfoot Strike

Video 3: Pressure Tracing – Heel Strike

What you will also notice is that in all three videos the center of pressure marker passes right under the second metatarsal head toward the big tow at toe-off. Ever wonder why second metatarsal stress fractures are the most common type of foot fracture in runners? That’s why – it’s due to bending in late stance, not initial impact since the second met isn’t even touching the ground at contact!

So next time you hear someone call themselves a supinator, ask them exactly what they mean by that. My guess is most people don’t even know and were simply told that by someone else who watched them run. You can direct them to these videos because just as pronation is a completely normal part of the gait cycle, so is supination.

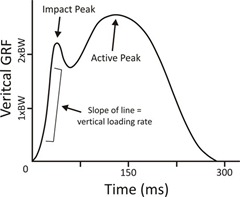

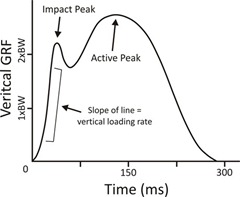

Interesting that the rearward migration of the center of pressure marker on the plot decreases as you go from fore, to mid, to heal strike. The heal strikers have no rearward movement of the the center of pressure. I guess this is one of those “duh” of course kinds of observations but still neat to see with real data rather than anecdote. What I’d like to see is how the movement of the center of pressure (along the two dimensions presented–sagittal and coronal) is related to peak loading. We already know that it is qualitatively right? Forefoot strikers tend to have lower peak loading, etc… But this approach would allow for a more quantitative investigation. So would be neat to see the mathematical relationship between the direction, shape of path, and rate of change of the center of pressure vector with that of the loading function.

There are some rare individuals who neither pronate nor supinate, usually after massive traumatic injury or rear foot fusions! Pronation and supination, as you’ve already stated, are normal motions in gait. It’s when, and how much, and how it relates to stress within tissues.

Good point on that exception :)

—-

Pete Larson’s Web Links:

My book: Tread Lightly – link to ow.ly

Blog: https://runblogger.com

Twitter: link to twitter.com

Facebook: link to facebook.com…

good post, pete. also worth noting on 2nd met stress fractures is their relationship to foot structure and stability/mobility of the runner.

both a forefoot varus and morton’s toe are examples of structures that limit the ability of the runner to get the big toe down to form a stable tripod. if you can’t get the big toe down, the 2nd met will be accepting greater forces at toe off…and it’s not hard to see how that can increase stress fracture risk

a person can also have strength or mobility deficits that basically cause the same issue.

examples:

*inadequate abductor strength can cause a cross over gait (running with feet on the same line rather than on separate tracks below the knees and hips)…limiting ability to get big toe down

*limited hallux ROM

Eric Johnson, Manager

Ultramax Sports

http://www.ultramaxsports.com

My personal feeling is you can add shoes with toe pockets that are difficult to flex and extend to the list of risk factors for 2nd met stress fractures – if the toes cn’t flex well to take the load off the met heads, more strain put on the mets. Vibrams are the only shoe that ever cause my mets to ache…

—-

Pete Larson’s Web Links:

My book: Tread Lightly – link to ow.ly

Blog: https://runblogger.com

Twitter: link to twitter.com

Facebook: link to facebook.com…

Quite obvious on videos taken on a treadmill too (he is a midfoot striker)

link to youtube.com…

It’s not that obvious on my own stride, but it’s still true.