A new study was just published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology that showed that adopting a midfoot strike is an effective way to reduce the impact loading rate during running. The study was conducted by a group from France and Canada (including my friend Blaise Dubois) and is titled “Impact reduction during running: efficiency of simple acute interventions in recreational runners.”

A new study was just published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology that showed that adopting a midfoot strike is an effective way to reduce the impact loading rate during running. The study was conducted by a group from France and Canada (including my friend Blaise Dubois) and is titled “Impact reduction during running: efficiency of simple acute interventions in recreational runners.”

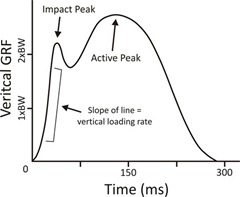

Impact loading rate is essentially the speed at which ground impact is applied to the foot and leg at initial ground contact in running (for more in-depth discussion of this, read my “Facts on Foot Strike” article in Running Times), and it is of interest because previous research has suggested that high loading rates may increase the risk of stress fractures. What is interesting about this study is that they looked at the comparative effectiveness of several methods for reducing impact loading rate: 1) adopting a midfoot strike, 2) increasing stride rate by 10%, and 3) wearing racing flat shoes.

The authors took nine habitually heel striking runners and had them run trials on an instrumented treadmill in both typical running shoes at their normal cadence with their normal footstrike, and then compared impact results to those obtained under each of the three conditions mentioned above, or when all three were combined at the same time.

Results indicated that adopting a midfoot strike or a combination of all three experimental modifications together resulted in complete absence of an impact peak and a significantly reduced impact loading rate (by approximately 50%). Increasing cadence by 10% or switching to racing flats in isolation did not significantly alter impact variables. They also found that pre-contact muscular activity in the gastrocnemius (calf) was higher, and activity in the tibialis anterior was lower in the midfoot strike and combined treatments.

Based on these results, the authors conclude the following:

“Our results show that the most efficient solution for acutely reducing LR is to run with a MFS pattern ….The reduced LR observed in habitual forefoot strikers or resulting from a shift from a rearfoot strike to the MFS pattern in habitual rearfoot strikers as observed in the present study may be associated with a lower risk of running-related injuries, and especially tibial stress fractures (Daoud et al. 2012). However, it may also cause collateral noxious effects such as metatarsal stress injuries, shin splints, and muscular and tendon injuries if not carefully and progressively conducted (Lohman et al. 2011). Further studies should determine whether the transition towards a consistent MFS pattern in the long-term is possible and not associated with other risks of injuries such as Achilles tendinopathy.”

A couple of points warrant mention about the results. First, the authors point out that the racing flat they used for all subjects was lighter and less structured than the training shoe employed for the “normal” condition, but it actually had a 2mm greater heel-forefoot drop than the training shoe. As such, it was not “flatter” and thus may not be representative of how a racing flat with a lower ramp angle might affect the variables under consideration. Second, even though increasing cadence did not significantly reduce loading rate in this study, previous research has shown that increased cadence can reduce loading of the knee and hip joints. It’s important to keep in mind that loading rate is just one variable to consider when it comes to injuries, and it has been most closely linked to stress fracture risk. Thus, different injury types may respond best to different types of intervention.

I am left with a few questions, and I hope that I can get Blaise Dubois to drop by and answer them in the comments.

1) I’m curious, as I always am, how much inter-individual variation there was in response the the various treatments. In other words, did some people experienced markedly reduced loading rate via an increased cadence or a change in shoes?

2) Unlike this study, Chumanov et al. found significant changes in muscle activity when runners increased cadence by 10%. I’m wondering if the lack of change in the study discussed here might be related to the smaller sample size (9 vs. 45 runners).

The take home message would be that if you have a history of stress fractures, foot-strike modification might be one method to try, but any change must be gradual as altering foot strike can stress other tissues in new ways that they are not used to (e.g., foot, Achilles tendon.)

With respect to your question #1, with a study size of n=9, it wouldn’t be overwhelming to see a longitudinal data plot of loading rates under the various conditions. Example is here

link to wiki.stdout.org…

I really like seeing the raw data myself since I’m fascinated by the individual responses to various interventions. I think Blaise is going to address some of the questions I had.

—-

Pete Larson’s Web Links:

My book: Tread Lightly – link to ow.ly

Work: link to anselm.edu…

Blog: https://runblogger.com

Dailymile Profile: link to dailymile.com…

Twitter: link to twitter.com

I wonder what the rear foot inversion moment graphs look like.

Hi Pete,

It’s a pleasure to comment (with my horrible English). Will try to be brief.

1. The average VLR of all participants together was lower when increase cadence, but not significant… so yes it’s possible that the small sample size was the reason.

2. The average cadence was 172. (hight for recreational runners)… so it’s possible that the VLR didn’t change as much when cadence increase to 189 (10%) than someone starting to 150 and changing for 165 (more common with my patient)

3. In my practice (not nine but thousands of patients) there is a lot of inter-individual answers to biomechanical interventions. I don’t have a sophisticate plat form integrate to my treadmill but I use various very simple things to quantify the impact force, like the noise at the impact (suggest by Dr Davis to be a valid intervention) and an accelerometer place on the treadmill.

My clinical point : every runner is different and prescription/advices to

different individuals have to be personalized. Indeed, it is possible to

decrease the impact force of runners (mostly the VLR) by modifying running

form. However, strategies which cause significant reduction in heard impact may

be different from one runner to another, and have to be recommended

accordingly. Most durable (automatic instead of voluntary) and most simple

interventions will be preferred.

Most of the time, I use these four interventions with

runners when trying to decrease the impact force, number 1 being my most

frequent and effective intervention.

1. Minimize shoe interference (decrease cushioning and ramp)

2. Increase step frequency / shorter stride (170 to 190 steps

per minute)

3. Voluntary reduction of impact noise

4. Midfoot strike

Hi Blaise,

I’m curious about one of your intervention. In your practice, do you sometimes use only the first intervention (minimize shoe interference) ? If so, does that intervention alone is enough to increase stride frequency / shorter stride?

Yes…

Yes for most of runners…

The average increase of cadence to our clinic (hundreds of patients calculated specifically for that) from their usual shoes to barefoot is 10 (0 to 20 depending of the client). For minimalist shoes (compare to traditional-maximalist shoes) is very variable. Some have the same result than barefoot, some no difference. It’s depends the client and how much minimalist is the shoes.

In my short experience with transitioning to a midfoot strike, I have also noticed an increase in gastrocnemius (calf) usage (sore after running) compared to when I ran heel striking. This was in conjunction with switching to a zero drop shoe. While the evidence is anecdotal, I can tell there is less stress on lower body joints, suggesting a decrease in loading rate. My wife experienced similar results when she switched to a zero drop shoe and midfoot strike. So my “seat of the pants” results are similar to those found in the study. Thanks for sharing.

http://www.barefootbrett.com

Hi Pete and Blaise. I can consider myself a mid foot striker: I tend to land with both heel and ball of the feet; I land with the whole outside of my feet, in other words. This happens when I run on a standard shoe (Saucony Ride 4, Muzuno Wave Elixir 7) or even a shoe with slyly less offset, as the Saucony Triumph 9. Thing is, as sonn as I wear a flatter shoe (Inov8 195; 2mm drop) I become a forefoot striker and land with the ball of the feet first. I chaged to Invo8 and I first love the feeling of the terrain; but, after some running seasons I experinced calf pain and, unfortunatelly, develop difficult-to-cure plantar fascitis after stepping on an acurate stone (I am totally recover by at this point). Question is: is it woth another try in more minimalitic shoes? Or shoud I stay the way I am with more or less “normal” shoes? P.S: I am really enjoying Pete`s book at the moment. Very interesting :D

I’d say stick with what works that allows you to run pain free and accomplish the goals that you have for your running. The end goal need not be zero drop for every runner, just what works best for each individual. Thanks for reading my book!

—-

Pete Larson’s Web Links:

My book: Tread Lightly – link to ow.ly

Blog: https://runblogger.com

Twitter: link to twitter.com

Facebook: link to facebook.com…

Thaks Peter. I think I will stay more or less the same way, but the researcher in me will try to seek new shoes to run with…I guess you will undestand. At some point I will try something like Kinvaras, which does not look as “dangerous” to me. And probably combine them with some barefoot running in the beach near my home; running on sand is something I have always donde in my youth with no trouble at all.

Yep, our curiosity gets the better of us :) Happened to me and glad I started to experiment. And yes, the Kinvara is a great and pretty safe choice for an experiment – you may actually find you don’t want to go back!

—-

Pete Larson’s Web Links:

My book: Tread Lightly – link to ow.ly

Blog: https://runblogger.com

Twitter: link to twitter.com

Facebook: link to facebook.com…