I did a 5x400m track workout on Wednesday (was supposed to be 6×400, but lightning and torrential rain put an early end to the workout!). As usual I was wearing my Garmin 620, and one of the cool features of the watch is that it computes your cadence for you without any additional gadgets or equipment needed. The workout consisted of running 400m at about 20-30 seconds faster than 5K pace, walking about 100m for recovery, then jogging 700m or so to prep for the next 400.

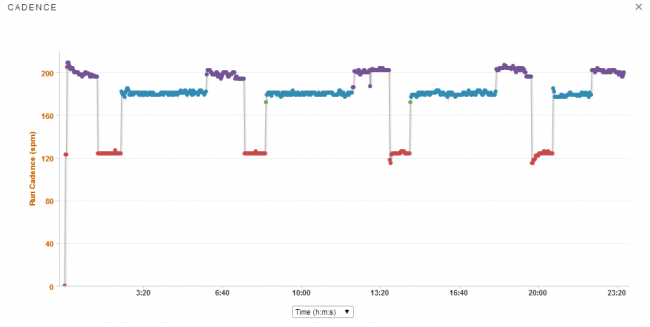

Every once in awhile I’ll check my stats out on Garmin Connect, and I happened to glance at the cadence graph for the workout – I always forget that the 620 does on-board cadence recording. Anyway, here’s what the graph looked like:

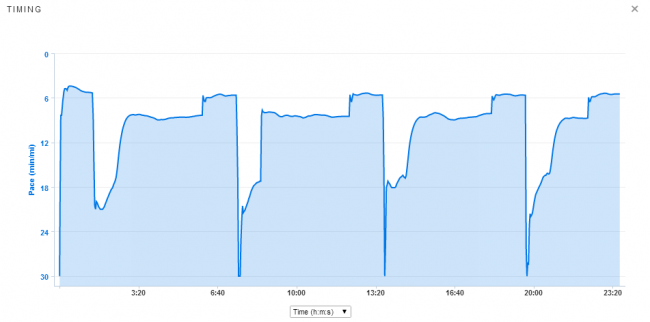

Here’s the corresponding pace graph:

I was struck by the regularity of the pattern – it’s almost like shifting gears. My walking cadence was around 125 steps/min, easy run cadence (8:00-8:30 min/mile) about 179-181 steps/min, and my fast running cadence (5:30-5:40 min/mile) was 200-203 steps/min. The pattern repeated almost perfectly with each cycle – my body settled into it’s preferred cadence for each speed/gait.

I’ve written before about the “myth of the 180 cadence,” which is basically the erroneous suggestion that everyone should aim to run at a cadence of 180, and I covered the topic extensively in my book. Though I do tend to run right at 180 at my easy pace, my cadence clearly changes with speed. Once I push the pace under 6:00/mile I’m up around 200 steps/min. 180 is not a magic number, and it’s not a number that every runner should aim for at all times.

Knowledge that cadence varies with speed influences my approach to dealing with runners as a coach and in the clinic. For example I’ve found that with my beginner 5K group cadences are often quite low – many are under 160 steps/min. But, I’m hesitant to change this since they are typically running 11:00/mile pace or slower when they first start out. Cadence will vary with pace, and this needs to be taken into account when assessing whether someone has a possible issue with overstriding (some beginning runners do, others do not).

In the clinic I often find that overstriding tends to be a bigger issue when runners increase speed. Since speed is a function of stride rate and stride length, some runners will increase speed by upping cadence, others will tend to try to reach out front with the leg and overstride (watch the final 0.10 of a local 5K and you will see a ton of this). Yet others can make use of good hip extension to increase stride length on the back side.

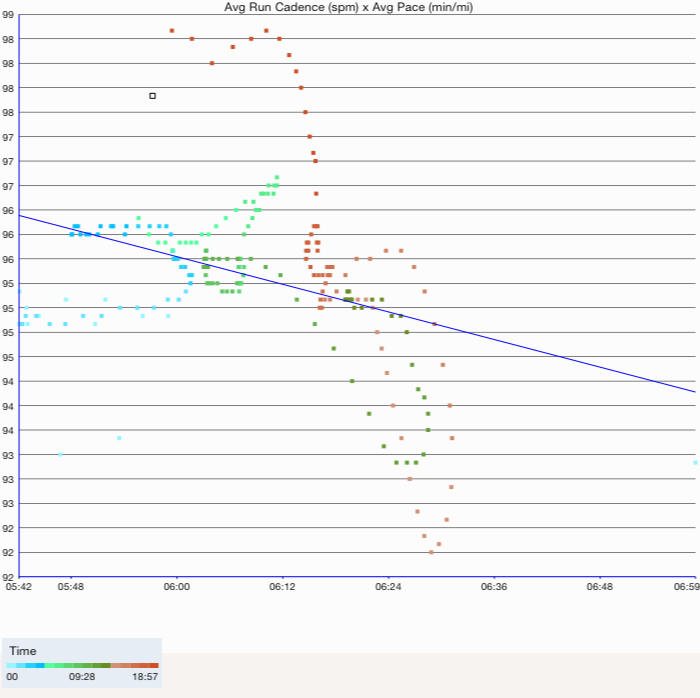

As an example of the latter, below are some data that I compiled from a video of the 5000m men’s final taken by physical therapist Jeff Moreno at the 2012 US Olympic Trials:

Based on the filming frame rate provided by Jeff, I was able to calculate cadence for each of the runners from the video (order is the order in which they pass the camera at this point of the race, not the final finishing order; details on the other measurements can be found here):

| Order | Name | Cadence | Contact Time 1 | Swing Time | Flight Time |

| 1 | Bernard Lagat | 195 | 0.143 | 0.471 | 0.167 |

| 2 | Galen Rupp | 187 | 0.138 | 0.505 | 0.176 |

| 3 | Lopez Lomong | 192 | 0.157 | 0.467 | 0.157 |

| 4 | Andrew Bumbalough | 202 | 0.148 | 0.448 | 0.143 |

| 5 | Mo Trafeh | 191 | 0.171 | 0.457 | 0.143 |

| 6 | Benjamin True | 192 | 0.162 | 0.462 | 0.148 |

| 7 | Elliott Heath | 205 | 0.162 | 0.424 | 0.138 |

| 8 | Hassan Mead | 191 | 0.171 | 0.457 | 0.143 |

| 9 | Scott Bauhs | 188 | 0.157 | na | 0.162 |

| 10 | Ryan Hill | 191 | 0.162 | 0.467 | 0.152 |

| 11 | Trevor Dunbar | 197 | 0.176 | 0.433 | 0.129 |

Aside from the fact that none of these elites were running with a cadence of 180, what I found interesting is that many have a cadence as many as 10 steps/minute or more lower than my fast running cadence at a pace that is well over a minute per mile faster (the winning time was 13:42, which translates to an average pace of 4:24 min/mile). I would likely attribute this to the elites having greater range of motion at the hip, with much greater hip extension than me. They can accomplish increased stride length through massive hip extension, whereas I, lacking that ability (I’m tight!), need to increase cadence to get to a higher speed.

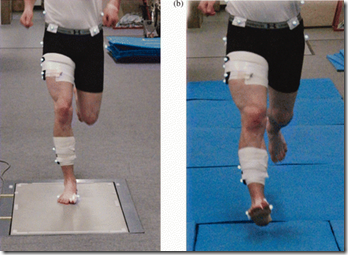

(Note: If you are unclear what hip extension is, it’s basically the extent to which the thigh swings backward toward the end of stance through toe-off – the picture below of Ryan Hall demonstrates hip extension well.)

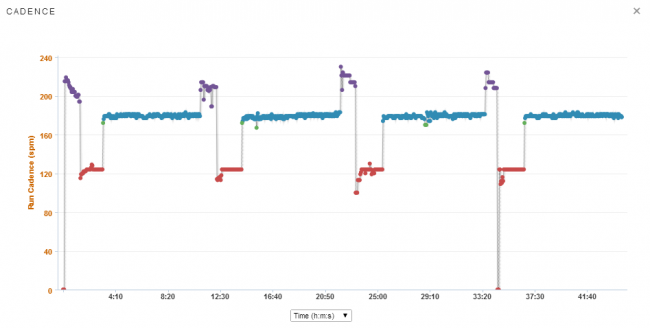

Supporting this, here’s another graph from a 4×400 workout I did last week in which I went near max effort on the run reps (which, sadly, is still 10-20 seconds per mile slower than the elites in the race above manged for a full 5k!):

At 4:40-4:50 min/mile my cadence shoots up to 210-220 steps/min. And you can also see the effect of fatigue coming in a bit in the purple dots above – on a few of the reps my cadence starts out high then trails downward as I slow down during the lap. I have some very interesting data from a 5K race I ran which I’ll share sometime as well – has some bearing on fatigue and gait change.

So what did I learn from all of this? For me, cadence is very consistent at a given pace on the track, and I seem to rely on cadence increase to accomplish faster speed than the elite 5000m runners do. Makes me wonder if I spent some time working on hip drive and hip mobility if that would benefit my speed…

Great insights Pete! This tells me what I have to work on, hip flexibility and mobility as you advised after my video analysis My cadence in the Market Square Day 10K was between 178-182 for average pace of 7:06. Do you think speedwork and what types of speedwork help the hips vs. doing no speedwork or little? Or are hip specific exercises the only way to move the needle…forward significantly

I feel like speedwork might be beneficial, if for no other reason than it’s a place where you can practice good form and work on developing those motor patterns.

For the life of me I can’t seem to get my cadence much above 160-165. There is very little difference in turnover between an easy jog (~10:30) and a fast cruise (~9:15), road or trail. It’s only when I’m flat out sprinting does my cadence really change. My Ambit2 hasn’t had onboard cadence for very long, so I’m not sure what it would look like at 5k speed, but I’d wager it would still be closer to 165 than 180. Not sure what that means, but there it is.

Corey, that sounds like a pretty reasonable cadence for that pace range. As long as you’re not overstriding (i.e., landing as close as possible to under your center of mass), you probably shouldn’t worry about your cadence. See Pete’s great post about the “myth of 180” that he linked to above.

For example, I run paces really close to Pete’s, but I achieve that with a much slower cadence (low 160s at easy pace, only just touching 180 at 5k pace). But I’m not overstriding – point being that decent form isn’t defined by cadence. It’s just easily measured, so it receives more attention than it probably should.

I would say at that pace probably not a huge worry. If you increase to 8:00/mile my guess is you are above 170. Would be an interesting experiment.

I would say that the elites have not only good hip extension, but are also probably getting good power from their glutes relative to body weight.

I would agree, I think one other possible explanation for my higher cadence is my heavier weight compared to the elites may reduce my flight time. I probably have 30-40 pounds on most of those guys.

Great analysis. Steve Magness did a similar analysis 3 elite 10k track runners as they kicked the final lap. One only increased cadence, one only increased stride length and the third increased both.

I remember that post, very interesting to see the different strategies.

I’m a very amateur runner, and only in the last few months did some research about cadence/turnover. I don’t know what my cadence was pre-research, but I started using an app (mobile metronome) to pace me at 180bpm. I noticed an immediate difference in speed and stamina though. Looking back, I can see that i was definitely loping originally, probably around 150bpm. Within 2 runs I had cut ~1 minute off my pace for 3 miles, from high 8s to high 7s. My hips are relatively inflexible as well (trying to work on that, but at 34, new flexibility doesn’t come easily); I can increase speed to an extent at the same cadence without over-striding, probably down to ~ 6:45 pace, but beyond that, I definitely have to move my feet faster. This stuff is all very interesting though, there are definitely lots of people who feel that 180 is the magic number, when, like you’ve shown, that’s going to depend significantly on your running style and flexibility.

Peter, forgive me if I am wrong but as I understand it the 180 cadence is the cadence at which one runs most efficiently. I agree that if running slower it might be lower and if running faster it might be higher but it wouldn’t be efficient at either. The slower cadence leads to a bouncy stride which is wasting energy and the faster pace is unsustainable for anything but short distances because it also costs too much energy. I do agree though that working on our hip mobility and perhaps strength would allow us to run faster by increasing our stride length (but still having our foot land underneath our centre of gravity) and keeping a more efficient cadence. Interesting topic and would be nice to see some research done on average runners.

There has been a lot of research on this topic actually, and the cadence at which a given individual is most efficient is variable from person to person, and most definitely not always 180. Wrote a lot about this in my book, in particular the Cavanagh references here: link to treadlightlybook.com. Not aware of any research showing that 180 is optimal.

Very interesting topic–I agree that cadence seems to be speed-dependent and not fixed for most runners. A couple of questions, if Pete or other experienced runners could weigh in:

If the problem is overstriding, will consciously increasing cadence fix the problem?

For a runner who is not overstriding, what would be the pros/cons of changing cadence at a given speed?

There has actually been research showing that increasing cadence by 5-10% reduces loading at the knee and hip, so it accomplishes the goal: link to runblogger.com

The difficulty is knowing what is contributing to your stride length at a given cadence – reaching out front, flight time, hip extension, etc. This is where video can be helpful. This is why it isn’t so simple to say everyone should run at 180 – every case really needs to be considered individually. I’d like to see studies that look at forces/efficiency as it relates to extension of the shin at contact for example, no sure of any off the top of my head.

Awesome post. Totally support the notion that cadence changes with pace and ROM.

Interesting.

I’ve always noticed that while my easy pace is about 180, when doing intervals I bump up to near 200.

I’ve wondered if somehow I need to work on my cadence at the fast pace to bring the cadence back to 180, but now I suspect not.

Nope, cadence change with speed is normal.

I Peter,

Congrats.once again for your blog. A huge source of usefull information. I’m a big fan and reader from Belgium, Europe.

I would suggest another hypothesis: considering your Garmin measures cadence without podometer I wonder if your cadence is not simply wrongly estimated by an algorithm calculating your cadence… from your pace.

Dr Cucuzella says cadence should not vary too much with pace. He demonstrates that in several videos.

That being said, I registered an increase of my cadence too when I approach my max speed.

I attribute that to the limit of my body/flexibility , not being able to lengthen my stride without altering my gait. From a certain cadence, we compensate by increasing cadence to an excessive level.

A beautiful counter example is to observe Mirinda Carfrae. The Aussie Ironwoman has one the most beautiful running technique on earth. She runs a marathon in 2h50 after 3.8km swim and 180km bike under heat with a nice 180 steps tempo and a forefoot strike. The length of her stride is tremendous … And all this giving the impression it is an easy job.

Thanks Yves! I’ve actually measured my cadence with the Garmin 620, my iPhone, and a foot pod in the past. All are very consistent at counting steps. Where they fail is converting that into a pace, but that is handled by GPS in the watch and on iPhone. I’d have to disagree with Mark if he says that cadence shouldn’t vary much with pace. Alex Hutchinson also wrote a nice post showing the same thing: link to sweatscience.com

Hi Pete,

Good observational article. I’ve read your book which is great, and as a running coach I would definitely like to see you work on greater drive and hip extension given your results, over a few months and see whether a reduced cadence with greater drive might achieve a better result, i.e. more efficient, speed over time, say in your 5km TT. Whilst I’d agree that 180 may not be the magic number, you will need extremely good co-ordination to maintain an efficient rate of 200+ as was posted, this requires alot of energy. As you’ve written I try to get my runners to increase their cadence by 5-10% through good technique application, but that is because they are all well under the 180 mark anyway. Further to that point & to respond to Chuck, increasing cadence can only be effective if practised correctly, as in each stage of the gait cycle is practised so that the foot picks up from the ground quickly, and glutes are activated early in the drive phase. I find Mark Cuccerella’s video very good for this explanation, and combined with many track nased running drills very good for developing these motor patterns.

Thanks Mark, definitely something I need to keep working at!

Peter,

Great post! I think when you look at the elites, you see above 180, closer to 190 for all. Light weight, years of training at a high level, and genetics. When I was 34 I set all my PRs after about 10 years of 40-50 a week with reg hills, and speed. (5K 16:11) I believe Hill work, (30-60 sec), up a moderate incline where you can get a good pace going will help your push off and extention. There is no better way I have found to increase both at the same time. Do 6 weeks of hills, then sharpen on the track keeping a lower rep hill workout once a week to maintain. It always worked for me, I found I had more power and extension when I hit the track. :)

Hills and speed are indeed a great combo. Been doing a lot of both the past few months, hoping it pays off this Fall!

Pete, nice post. I have been using Optogait for evals and almost everyone increases cadence as they decrease contact time with increase in speed. this is an objective tool that tells what it is

Best

Mark

I’ve looked at the Optogait a few times, pretty cool device!