So far this week I have written about studies that have looked at foot strike patterns in in minimally shod or barefoot runners. A study of the Tarahumara in Mexico showed that even among individuals who habitually wear minimal footwear, foot strike patterns are variable during running. A study of the Hadza in Tanzania suggested that development of a midfoot strike pattern might be associated with running experience, as adult males who run more frequently while hunting tended to MFS, whereas adult females and children tended to rearfoot strike.

So far this week I have written about studies that have looked at foot strike patterns in in minimally shod or barefoot runners. A study of the Tarahumara in Mexico showed that even among individuals who habitually wear minimal footwear, foot strike patterns are variable during running. A study of the Hadza in Tanzania suggested that development of a midfoot strike pattern might be associated with running experience, as adult males who run more frequently while hunting tended to MFS, whereas adult females and children tended to rearfoot strike.

In this post we’ll take a look at another study on foot strike, in this case the influence of surface hardness on foot strike type in habitually shod runners who were asked to run barefoot in the lab. The study, led by Allison Gruber, was published in 2013 in the journal Footwear Science. They were interested in trying to determine whether pain associated with a barefoot heel strike on a hard surface might trigger a shift to a midfoot or forefoot strike.

Here is the abstract (full text is available here):

Footfall patterns during barefoot running on harder and softer surfaces

Allison H. Grubera, Julia Freedman Silvernaila, Peter Brueggemannb, Eric Rohrc & Joseph Hamilla*

Footwear Science, Volume 5, Issue 1, 2013, pg 39-44

Abstract

It has been suggested that the development of a thick, soft midsole of running shoes over the past 30 years has been primarily responsible for the majority of runners adopting a rearfoot or heel-toe footfall pattern thus deviating from a more ‘natural’ forefoot pattern. The purpose of this study was to determine the freely chosen footfall pattern when running barefoot on a harder versus a softer surface. Forty habitual rearfoot runners performed two running conditions: barefoot over a harder surface and barefoot over a softer surface. Three-dimensional motion analysis and ground reaction force data were collected to measure the ankle angle, vertical impact peak and strike index. The kinematic and kinetic parameters were used to confirm the footfall pattern in each condition. Only 20% per cent of the participants ran with a midfoot or forefoot pattern on the soft surface whereas 65% of the participants ran with a midfoot or forefoot pattern when running on the hard surface. Out of the 80% of participants that maintained a rearfoot pattern on the soft surface, 43% of these participants ran with a midfoot or forefoot pattern on the hard surface. These results suggest that, while running barefoot, the hardness of the running surface may be a significant factor causing an alteration in a runner’s footfall pattern.

Methods

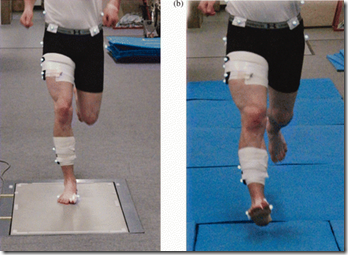

The researchers recruited 40 habitually shod runners who were confirmed to be rearfoot strikers in their typical training shoes. They had each runner run trials in the lab along a 25 m runway equipped with a force platform. Trials included two conditions: 1) concrete runway with no cushioning (the hard surface); 2) runway covered with 20mm EVA foam mats to simulate characteristics of a shoe midsole (the soft surface). Foot strike patterns and a variety of other biomechanical measurements were recorded for each subject in both conditions.

Results

On the soft surface 80% of the runners ran with their usual heel-striking pattern, 17.5% ran with a midfoot strike, and one person ran with a forefoot strike. On the hard surface, 35% of subjects ran with a heel strike, 27.5% ran with a midfoot strike, and 37.5% ran with a forefoot strike. Statistical analysis confirmed that there was a significant shift in foot strike patterns between the hard and soft surfaces.

Commentary

What I liked about this study was that it asked and tested a simple question: What happens if habitually shod heel strikers run barefoot on a hard vs. a soft surface? What they found is that runners tended to shift to a midfoot or forefoot strike on concrete, but most continued to heel strike on the cushioned surface. This suggests that the presence of cushioning allows runners to heel strike comfortably and could indicate why heel striking is commonly observed in shod runners on hard surfaces, whereas barefoot runners tend to shift to a midfoot or forefoot strike on hard surfaces. Moving to a midfoot or forefoot strike allows the Achilles tendon and calf muscles to assist in attenuation of impact forces and could make running on hard surfaces more comfortable.

The results here could also explain why habitually barefoot or minimally shod people like the Daasanach, Tarahumara, or Hadza children and adult women have been observed to heel strike while running slowly on natural sand/dirt surfaces, whereas experienced Kalenjin runners moving fast tend to midfoot or forefoot strike on such surfaces. It might also explain why approximately 50% of runners in Vibram Fivefingers have been observed to contact on the heel when running on asphalt – there may be just enough cushion present in minimal shoes to allow this to be done comfortably if the pace is not too fast.

One interesting finding here was that 20% of the runners switched from their typical heel strike in shoes to a midfoot or forefoot strike even on the soft surface. The authors reported in their Discussion section that some of these subjects had previous experience with barefoot running, and that they indicated that they were more comfortable with the MFS/FFS when running barefoot. In other words, previous experience running barefoot could have led to development of modified form in this condition (similar to the role of experience in the Hadza runners). I would also suggest that even though cushion is present in both conditions, plantar sensation when running barefoot on a mat vs. with a shoe on the foot might differ and could explain some of these changes.

One other interesting finding was that 35% of subjects continued to heel strike when running barefoot on concrete. The authors suggest that the lab runway may not have been long enough to induce discomfort necessary to trigger a change in foot strike. However, I have observed a similar proportion of barefoot runners heel striking on asphalt during a race, so length of the runway may not have been the only factor. It may be that a move to a less prominent heel strike could make barefoot heel striking comfortable enough for some runners, or it could be that some runners need more experience before adopting a different foot strike when barefoot on a hard surface.

As with most studies, this one provides some answers but also raises new questions. For example, I wonder if there is an individually specific threshold combination of speed and surface hardness that triggers a shift in foot strike to attenuate the impact forces associated with a heel strike? Also, why do some people shift but others do not? How much experience is required for a shift to occur, and are there some people who will never shift their foot strike? What role does plantar sensation or abrasions with the ground surface play in determining foot strike? To me, the continual search for answers to questions like these is what makes science so much fun.

Maybe those who remain heel strikers when barefoot are able to withstand impact forces and such better than those who ff or mf strike. Some of us tend to be a little more sensitive, and it seems like we’re the kind of people who tend to gravitate toward the barefoot/minimalist stuff. I’ll just simply tear my feet up when barefoot if I don’t remain mindful and slow my pace. The skill I gain running barefoot makes my shod running better and more satisfying.

I’d be curious to know how variable the width of the heel fat pad can be and if that might play a role here.

Gracovetsky (2001) discusses initial contact as a compression energy ‘pulse’ that is required to help stabilise the spine during locomotion (walking and running). The pulse is reshaped and delayed (or filtered) via numerous soft tissue structures as it travels proximally.

“this filtering process is essential to provide a perfectly matched pulse to the spine kinematics regardless of ground surface hardness so that a maximum transfer of energy occurs”

This is interesting, but I think missing a major part of the story. Everyone concentrates on the foot strike, however to use a man-made suspension analogy, the foot and where it lands (FFS or HS) is the damper and the leg and all its joints are the actual spring. Therefore to concentrate on only how the foot lands is to miss out most of the picture. You can land on what appears to be your heal barefoot as long as you are bending your legs correctly, using them as suspension.

Another feature never mentioned is that the human foot is always striving for stability. Therefore your gait will adjust to softer services by adopting more of a HS than a FFS when landing on surfaces like sand. This is by design and not the runner’s preference for landing on the heal.

Everyone is so caught up in FFS vs HS they are forgetting the basic bio-mechanics happening here.

Great study and I’m surprised that 35% of the runners continued to heel strike on concrete! I don’t think you can eliminate pace though and a sister study that just studied the effects of pace on heel striking would be interesting. My prediction is that a high percentage of runners would heel strike at a slow (11 min mile) pace while a low percentage would heel strike at a fast (6 min mile) pace. I’d expect that at some transition points the foot landing pattern would switch from heel to mid to forefoot landing. But I do agree that the transition points vary according to surface or shoes.

Speed will have an influence, wrote about one study here: link to runblogger.com

Great Post! Foot strike angle and type can be variable both within and between individuals, especially among habitually barefoot individuals. Finally, what do these results mean for habitually shod individuals who run mostly on pavement and treadmills, and wonder how to make sense of diverse arguments about minimal shoes, cushioning, and strike type? First, the restricted variation in strike type among habitually shod runners today may be a recent phenomenon, and it would be useful to test if runners adopt more variation when running on trails rather than on pavement or treadmills.