I’ve written a lot about foot strike variability over the years, but I still see people make claims that heel striking is bad, or that barefoot and minimally shod runners don’t land on their heels.

I’ve written a lot about foot strike variability over the years, but I still see people make claims that heel striking is bad, or that barefoot and minimally shod runners don’t land on their heels.

Personally, I view foot strike as one aspect of running form that varies with a range of factors. These factors would include running speed, running experience, surface hardness, surface incline, fatigue, footwear type or the lack thereof, etc. For example, I think we tend to see a shift more toward the forefoot side of the spectrum when experienced runners run fast on hard surfaces, particularly if barefoot. We see a shift more toward the heel strike side when inexperienced runners run slowly on soft surfaces or in heavily cushioned footwear. Mix and match these factors and we can get a variety of different foot strike types, and it’s unlikely that any one set of conditions will yield identical responses in all runners exposed to them (because people are variable).

As an example of the influence of both external variables on running foot strike and individual variability within the same condition, I thought it might be interesting to take a look at a research study that was published last year. Authored by Daniel Lieberman, the study takes a look at foot strike patterns among traditionally shod and conventionally shod Tarahumara Native Americans from Mexico (full text is available here). The running prowess of the Tarahumara was made famous by Christopher McDougall in his book Born to Run. That book, published in 2009, was largely responsible for kicking off the form and footwear debates that ensued over the following years, and the Tarahumara thus make for a great running form case study.

Here’s the abstract of the study:

Strike type variation among Tarahumara Indians in minimal sandals versus conventional running shoes

Daniel Lieberman

Journal of Sport and Health Science, Volume 3, Issue 2, June 2014, Pages 86–94

Abstract

Purpose

This study examined variation in foot strike types, lower extremity kinematics, and arch height and stiffness among Tarahumara Indians from the Sierra Tarahumara, Mexico.

Methods

High speed video was used to study the kinematics of 23 individuals, 13 who habitually wear traditional minimal running sandals (huaraches), and 10 who habitually wear modern, conventional running shoes with elevated, cushioned heels and arch support. Measurements of foot shape and arch stiffness were taken on these individuals plus an additional sample of 12 individuals.

Results

Minimally shod Tarahumara exhibit much variation with 40% primarily using midfoot strikes, 30% primarily using forefoot strikes, and 30% primarily using rearfoot strikes. In contrast, 75% of the conventionally shod Tarahumara primarily used rearfoot strikes, and 25% primarily used midfoot strikes. Individuals who used forefoot or midfoot strikes landed with significantly more plantarflexed ankles, flexed knees, and flexed hips than runners who used rearfoot strikes. Foot measurements indicate that conventionally shod Tarahumara also have significantly less stiff arches than those wearing minimal shoes.

Conclusion

These data reinforce earlier studies that there is variation among foot strike patterns among minimally shod runners, but also support the hypothesis that foot stiffness and important aspects of running form, including foot strike, differ between runners who grow up using minimal versus modern, conventional footwear.

Methods

Lieberman traveled to Mexico and collected kinematic data from 20 Tarahumara. Twelve of these individuals wore only traditional huarache sandals (see photo at top of post for image of huaraches), and eight wore conventional running shoes. After a five minute warmup, subjects were filmed while running 15 meters along a flat, natural surface free of grass and rocks. Each subject ran the 15 m trials until three usable videos were recorded for each. A variety of biomechanical variables were measured from the video sequences.

Results

Minimally shod Tarahumara that ran their trials in huarache sandals exhibited the following foot strike patterns: 40% midfoot strike, 30% forefoot strike, 30% heel strike. In contrast, Tarahumara in conventional running shoes landed on the heel 75% of the time and on the midfoot 25% of the time. No forefoot strikes were observed in the conventionally shod runners. Of the other biomechanical variables measured, only overstride angle differed – minimally shod runners tended to land with the ankle in a position more underneath the knee at ground contact.

Commentary

These results demonstrate two things to me:

1. Footwear does have an influence on foot strike. Those Tarahumara who typically wear conventional shoes and ran their trials in this type of shoe tended to heel strike 75% of the time. This is consistent with other studies that have found that 75% or more of traditionally shod runners land first on the heel.

2. Foot strike patterns are variable in Tarahumara runners wearing huarache sandals. Almost a third of them heel strike, and there is no overwhelmingly predominant pattern exhibited by this group. Lieberman himself writes: “…minimally shod Tarahumara runners appear to be best characterized as midfoot strikers who also employ forefoot and rearfoot strikes. These data therefore partially support but also modify earlier anecdotal reports that Tarahumara runners who use huaraches primarily FFS (forefoot strike).” As the source of these anecdotal reports, Lieberman cites McDougall’s book Born to Run and Scott Jurek’s book Eat and Run.

So here we have two levels of variability. Variability among groups due to the type of footwear typically worn, and variability within groups wearing similar kinds of footwear. It’s not as simple as saying that all huarache-wearing Tarahumara forefoot strike, and this suggests that there is no “perfect” or “natural” running form or foot strike that is or should be used under all circumstances by all people. Rather, running foot strike is dictated both by external influences (footwear here) and individual variation in response to a given set of conditions.

To me, this combo of adaptability and variability is what makes the study of human running form so fascinating – we are amazing and complex animals, and this is exhibited by both our incredible running ability as well as how we run.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like this one on foot strike patterns in Hadza hunter-gatherers.

Thanks Pete! … I find particularly interesting the similar and reasonably high step frequencies of ~175 steps/min in both groups … consistent with Lieberman’s advice (link to youtube.com) to not land hard on one’s heels and title of your book, “Tread Lightly”. Seems that is more important than what part of one’s foot strikes first or what kind of shoe (if any) one wears.

Interesting article. Well everyone needs to find his own way. Mine is the xero sandal 4mm way. Been running painfree forefoot and run my 10k’s in 36m

I’d be interested to know how the shoes influenced where they landed in relation to their center of gravity.

Thanks for the commentary!

Overstride angle did differ (less in sandals), but no differences in hip, knee, or ankle angles at contact between footwear.

But if those angles are the same on someone in flat-soled sandals and someone in shoes with elevated heels the only reason the latter is heel striking is the elevated heel of his shoe. Surely this can’t be the only difference?

That crossed my mind as well, Sean.

Thanks for sharing this Pete! I agree with you, humans are the biggest variable, there’s no all or nothing in running or really anything with us.

Hi Peter!

Sorry for the irrelevant question but are you going to write a review for the 1500V1?

Thanks.

Yep, should be soon, been running in them the past few weeks.

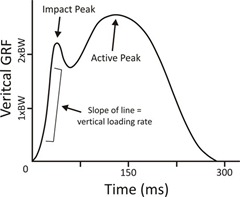

Would have been interesting if Lieberman looked at his ‘collision forces’ in the hurache wearing runners, since his main conclusion in the 09 Nature article is that FF running lowered these compared to shod RF strikers.

What do you think, Pete?

It would be interesting, but hard to do in the field.

agreed. Difficult…but not impossible :)

Sorry, Pete, but I have to disagree that the results (or at least my quick perusal of them) demonstrate that “[f]ootwear does have an influence on foot strike.” While the results are consistent with that inference, at least some of the causality almost certainly goes in the opposite direction, as heel strikers quite plausibly select out of minimal footwear into cushioned footwear.

That’s possible, but the minimally shod group were mostly rural Tarahumara whereas the conventionally shod were mostly westernized and lived in a town. I think the latter are more likely to wear shoes due to access and because they don’t live the traditional Tarahumara lifestyle. Furthermore, the observational data here are consistent with experimental studies on the effects of footwear and/or surface hardness on foot strike. For example, Squadrone and Gallozzi found that strike index is significantly lower when habitual barefoot runners wear conventional shoes: link to marchingbandwellness.com. Also, conventionally shod runners typically adopt a flatter foot strike or a forefoot strike when running barefoot.