Earlier today I was doing a phone interview with a reporter from the Chronicle of Higher Education and she asked me a question that I have been asked a lot lately: “How would you describe good running form?”

This is a question that a lot of people have opinions about (sometimes very strong opinions), but I still find it to be a really difficult question to answer. There are a lot of things I can point to that I consider to be aspects of bad form, such as overstriding, excessive side-to-side movement, etc., but really nailing down what represents “good form” can be tough, for reasons that I will outline below.

Whenever I think about the concept of “good” form, the evolutionary biologist in me perks up and turns the question around a bit and asks instead: “How are humans supposed to run?” I’m a firm believer that just like every other animal on this planet, we humans evolved to run in a certain way. The problem is that in modern society, the vast majority of us don’t run that way because we wear shoes. We did not evolve to run with shoes on our feet. I’m not passing judgment or trying to say that shoes are good or bad (I am a shod runner after all), I‘m merely pointing out the fact that wearing shoes changes our biomechanics in some fundamental ways.

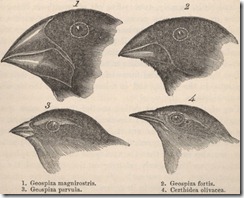

So, if I were to attempt to answer the question of how we humans are supposed to run, I would say you simply need to look to people who have never worn shoes and figure out what the majority pattern is. Turns out, Daniel Lieberman did this work for us, and found that the typical running form exhibited by habitually unshod runners looks more-or-less like this:

This child is forefoot striking and landing with a bent knee and a roughly vertically oriented lower leg – many suggest these days that these are the elements of good form, and I would not disagree. Just because Lieberman found that most habitually unshod individuals run with form like this does not mean that habitually unshod runners forefoot strike with every footstep (he observed a few habitually unshod heel strikers, and I have seen my kids do the same on occasion when running barefoot). Rather Lieberman demonstrated that most habitually unshod runners seem to forefoot strike most of the time. However, they also probably land on their midfoot sometimes, and on their heels sometimes as well.

Shoes are a game changer when it comes to our running mechanics because they alter the sensory information that comes in from our feet. I witnessed this firsthand a few months back when I ran a little experiment with some students in my Exercise Physiology class. We had been talking about running mechanics, and I decided to take them down to the lab for a little experiment. I had four students run on a treadmill in their shoes, then had them take their shoes off and run in their socks. All the while, I was filming them in slow motion at 300 frames/second. As the students were running, I asked the other students who were watching to tell me what they saw. In particular, I asked them how the runner’s foot was hitting the treadmill surface (note: this is a much softer surface than asphalt or concrete).

Upon reviewing the video with them, it turned out that all four students were heel strikers with their shoes on (one was asymmetrical with a midfoot strike on one side), and all switched to forefoot striking when they took their shoes off. No fancy analysis was needed – the kinematic change was as clear as day. One of the students who had participated claimed that it was “like magic,” and many were surprised to realize that their initial thoughts about what the runners were doing based on observations from just a few feet away were completely wrong.

The above anecdote demonstrates two things. First, removing their shoes fundamentally changed how each of these students ran. The reality is that there was no magic involved – removing their shoes altered the sensory feedback coming in from their feet, and they adapted accordingly. Second, form analysis is really hard to do with the naked eye – high-speed video is really necessary to accurately determine foot strike.

Our body is remarkably good at figuring out what to do in a given situation, and it’s for this reason that our form changes from what I consider to be “natural” when we put shoes on. It therefore comes as no surprise to me that the vast majority of runners in modern running shoes are heel strikers, and a substantial number of them are horrific overstriders (I’ve watched more than enough slow-motion race video to be pretty certain about this). There aren’t a whole lot of good data linking mechanics or footwear to specific injury risk, but I continually come back to the question of whether wearing shoes that dramatically change our form from what might be deemed “natural” might have some unintended or even possibly deleterious consequences. The human body seems to have evolved to move in a certain way when we allow it to run in its natural state, and monkeying around with that might not be such a good idea. Or maybe it is, as other human inventions have allowed us to do things in ways that we couldn’t otherwise. For example, my glasses/contact lenses allow me to read, and maybe cushioned shoes improve my ability to run on asphalt.

I’m not saying everyone should run barefoot or even necessarily in minimalist shoes, or that these are even necessarily better, but rather asking the question: Are modern running shoes and the biomechanical changes they allow/cause a good thing? What is the empirical evidence that a 12mm lifted heel and extensive cushioning are positives for our feet and legs? I for one don’t believe this question has been answered, though others involved in the shoe industry would appear to disagree. Take these responses by ASICS International Research Coordinator Simon Bartold to questions posed by Sneaker Freaker Magazine:

Do we really need shoes? There’s plenty of dudes running around the Kalahari in barefeet!

I think we do, especially in Western societies. We have been wearing shoes for thousands of years and have actually evolved to adapt to a ‘shod’ situation. There’d be many people who argue with that, but I think that we’ve now pretty much established that it’s good to have the heel raised in shoes. About 12mm is a good thing biomechanically, because you’re in a more efficient position. If you’re running around the Kalahari Desert you develop a lot of calluses, but it’s probably still desirable to have a decent pair of shoes rather than doing that barefoot.

You mentioned before about a 12mm heel height being ideal? Why is that the standard?

Well, that’s a very interesting question because it hasn’t been settled on at all. With ASICS we’ve always worked on a 10mm gradient. That’s the difference between the height of the forefoot and the height of the rear foot, so if you’ve got a cushion type shoe it might be 24mm and 14mm off the ground. A racing flat might be slimmer at 10mm and 20mm. We’ve done a lot of research on this and we understand that it actually puts your foot in a mechanically better position, makes it more stable, takes a load off the Achilles tendon… so there’s a lot of positives. There’s a lot of myths and all that sort of crap and the problem is that every time you add a little raise, people are going to say ‘oh but you’re removing the foot from the ground therefore you’re going to make it more unstable and you’re more likely to sprain an ankle’, which is complete nonsense. That’s scientifically unsustainable. There’s no evidence to say that happens at all.Ok. Myth #2. Running in barefoot is the best.

Instantaneous bullshit detection going on! This is very popular at the moment and there’s a lot of companies that have websites saying that barefoot running is the way to go. But I think if we look at everything that science tells us, which is what we have to place our belief in, then that statement would not ever be supported because of the ability of shoes to help improve biomechanics.

I agree with Bartold that shoes are generally a good thing, and I genuinely don’t think that barefoot running is going to be the answer for the vast majority of runners (myself included). However, I’m not so sure that there is a lot of published empirical evidence demonstrating that a 12mm lifted heel is ideal. Does a 12mm lifted heel make you faster, more efficient, or less likely to get injured? Why not 10mm, or 8mm, or 6mm, or 4mm, or 2mm? Do shoes really “improve biomechanics” as Bartold suggests? How do you define “improved biomechanics” anyway – what is the measure of improvement? Bartold even goes on to say in the interview that “…the thing about kids these days is that hopefully they’re pretty active, which means they will need some sort of meaningful midsole and elevated heel.” Does one really follow from the other? Have studies been published in peer reviewed journals that active kids are better off in shoes with thick midsoles and elevated heels? Seems that many of the kids that grow up running barefoot in Africa like the one in the video above turn out just fine when they compete at the international level as adults…

Another point to consider here from the above interview is that although I don’t think we have evolved to be shod, most of us who have been wearing shoes our entire lives have certainly adapted to them in ways that might make running unshod difficult, at least initially. Shoes can not only change our biomechanics the moment we put them on, long term shoe use can actually alter the anatomy of our feet and legs (e.g., hallux valgus due to wearing of shoes with highly tapered toeboxes, weakened bones in the feet, weakened calf muscles due to continued use of heel lifts). The consequences of this might be manifesting themselves in the form of injuries like metatarsal stress fractures in people who jump into barefoot or barefoot-style running too quickly. This is a whole different topic for discussion…

So, when I think about all of this in relation to the question “What is good form?”, I find myself thinking that good form in the shod condition might not be the same thing as good form in the unshod condition. Good form in a shoe with a 12mm heel lift might be different than good form in a zero drop shoe. Good form might be different on a track vs. a trail vs. a road. Good form might be different for a 4:00 miler vs. a 12:00 miler. Maybe trying to forefoot strike in a 12mm lifted shoe is a bad thing – maybe your body is heel striking because that’s what’s best in that condition. When you attempt to forefoot strike in a 12mm lifted shoe your foot is likely plantarflexed way more than it would be when barefoot so that you can land on the forefoot before the heel touches down, and perhaps that has deleterious consequences as well. Maybe a 12mm heel lift is good for your Achilles, but bad for your knees. We have tons of open questions, and hopefully answers will come with time. For now we are each left to experiment and find what works best for us on an individual level – maybe this is the best we’ll ever be able to do.

These are the reasons why I have trouble answering the question of what is good form. The logical answer to me as an evolutionary biologist is to run how we evolved to run. Is barefoot running form “good form?” I’d say yes, if you are barefoot, and perhaps in some kinds of shoes (for me up to about a 4mm heel lift I think). Is barefoot running form “good form” when wearing a pair of Brooks Beasts or Asics Kayanos? Maybe, but my gut tells me that you may be forcing your body to do something it doesn’t want to do in those shoes, and maybe that’s just as bad as heel striking when running barefoot on asphalt.

So, at the end of this giant brain dump, what have I concluded? Basically, I’m pretty convinced that we know how humans evolved to run (mostly, but not necessarily exclusively, like the Kenyan child in the above video), but translating that into the shod world is where things get difficult. I suspect that there is a point at which attempting to run barefoot-style in shoes might become counterproductive, but I’m not sure I know where that threshold is, or if it might be the same for every person. I have a gut feeling that trying to forefoot strike in a motion control shoe is ill-advised, just as transitioning too fast into zero drop shoes is a bad idea. Ultimately, I’m starting to feel like I should just defer to the wisdom of my own body – I feel like it knows what to do given the conditions I present it, and I’m finally starting to get a handle on which conditions it likes best (a benefit of having run in so many pairs of shoes the past few years). For me, those conditions don’t involve a 12mm lifted heel. Maybe your ideal conditions are different – your job is to experiment and find your comfort zone. Maybe that will look like the video above, maybe it won’t, but the journey can sure be a lot of fun.

Good post…speaks to me for sure.

What do I know? I know that reducing the drop on my running shoes and running with a more flexible sole has let me avoid Achilles Tendinitis. I think the optimal foot/leg strengthening is with minimalist shoes, but racing in shoes with a bit more protection lets you harvest this to maximum effect.

I strengthen in Nike Frees and race in Kinvaras..the latter if used every day would take me back to problems and the former if used for 26.2 miles would knock the snot out of my legs.

It’s a fascinating mystery ..I suspect every runner is quite different.

Thanks for sharing your story – I agree that we all are a bit different.

Strangely enough, my preferences tend toward either a softish shoe like the

Kinvara, or bare minimum like the Fivefingers or Merrell Barefoot. I’ve

found that I really don’t like shoes that have thick, firm soles – this

would include things like the Saucony Fastwitch 5 and New Balance Minimus

Road, or most anything with a heel lift above 5-6mm.

Pete

Great article! Thanks for the continued balanced research on barefoot and minimalist running. I enjoy your blog immensely.

Pete-Brilliant post. It did get me to thinking that the constant in this conversation is the importance of natural running form and technique. I think we are seeing more and more data identifies that there some key movements you body is engineered to do very efficiently, particularly with regards to running.

My understanding of unshod populations is that we see very consistent patters of movement. My understanding of a shod populations is where a wide spectrum of running styles are introduced, particularly movements that are nearly impossible to do in a more natural state or barefoot. Perhaps the most effective way to empower athletes is to deviate as little as possible from the movement your body is designed to do most effectively. If you can develop and rely and the things your body is designed to do, it may shift the role of shoes from crutch to tool.

Great post – I appreciate your insights and method of delivery, in particular how you are always willing to look at both sides of the coin. Keep up the good work!

Another epic post from the pen/keyboard of Pete Larson.

If nothing else, all this discussion promotes humans to experience more powerful connections with their bodies and the world around them. I believe this is a crucial part of figuring out what works best for us.

As you recommend, ‘experiment and find your comfort zone’. Let the masterpiece that is the human body guide us in our quest for ‘good running form’ enlightenment.

I just watched a quick video with author/coach Jack Daniels and he was talking about the variability of foot landing patterns. He agreed that everybody is different and no one foot stride (forefoot, midfoot, heel strike) is ideal because the “best” running form is the most efficient. Some runners are more efficient (as measured during a VO2 Max test) with a heel strike as opposed to a midfoot stride. Videos of Meb Keflizighi winning the NY Marathon show a heel strike, actually. So a particular runner’s best running form is what is most efficient for them in terms of oxygen consumption. You’ll never know without measuring it.

Jason – I definitely agree with you. It seems that to improve running economy and efficiency, runners must not focus so much on “proper form” since there are so many variations of human form in running motion. To get faster and fitter, we simply can train harder – improve our VO2 Max, get stronger and results will come.

I run with a group out in Spokane, WA called the Spokane Distance Project. Many of the guys are some of the fastest runners in the city, yet they are not sporting minimalist shoes. They wear your standard 12mm heel lift, stable running shoe. A few of the guys heel strike too. But despite all this, they are very fast and are getting faster. Just goes to show you that there are so many more factors involved in becoming a better runner, aside from form and footwear (not to say that they aren’t important).

Yet the more I think about it, these guys all share a “general standard running form” that is seen among elite/fast runners. While there are variations among each individual runner, all seem to run with a slight forward lean, little upper body/arm movement and a smooth, flowing stride. So who really knows for sure.

I think the whole “evolved” argument falls apart in modern society. When we don’t starve because we can’t run fast enough, there’s no weeding out of the weaker, lesser-evolved part of the population. To say we evolved to wear shoes is the biggest bucket of BS I see bandied about in the whole subject.

So the frustrating thing about Simon Bartold is that he speaks with such assurance and such authority. Of course he has to say that since the underpinnings of his compnay are in question. It would be nice to hear someone in his position admit to the questions that exist and that much research is required. I guess he thinks it is better to put down the rebellion rather than say it might have merit and that his company will evolve with new findings. We are committed to exploring. After all, he is still going to sell shoes. In my mind he lost all credibility by stating that this is “instanteous bullshit”. He lost all credibilty because he is afraid to admit we don’t have all the answers and he is acting only out of self preservation. I guess he is compelled too. Thank goodness for researchers like Pete, who are independent!!

Yet another shoe company rep poo-pooing the minimalist/barefoot movement! Well poo-poo to him too! The paranoid conspiracy nut in me is starting to think there’s a conspiracy afoot where the big shoe companies are trying to keep our feet imprisoned in unreasonbly lifted/cushioned shoes (there’s an idea for a movie there, I just know it!). :-)

I really liked your analysis Pete and your advice for everybody to just experiment for ourselves is the best out there. After all, everyone is different. I’ve tried running in a variety of shoes, trying both a heel-strike form and a forefoot/midfoot strike. I have found that my feet, and entire body for that matter, are much happier and stronger when I forefoot-midfoot strike in a shoe with a 0-4mm heel-toe drop. Also, using this “barefoot” style of running has really increased the enjoyment of my runs which has made ALL the difference in the world. Plus my calves have never been stronger or more ripped! Thanks for keeping up such an informative blog.

Right, Simon Bartold, this is why I switched to minimal running as a chronic heel striker with horrible form and bad injuries and am now injury free while simultaneously increasing my mileage. What Bartold says simply epitomizes the whole running shoe issue as exposed by Born to Run and Runblogger. Asics isn’t going to make any money selling less shoe. The shoes we wore thousands of years ago were not 12 mm lifts; they were thin sandals and such. Great post Pete, as always. Always good to get emotionally involved.

Pete, great post. I call instantaneous BS detection when Bartold says we have actually now evolved to run shod.

But I think the one thing that is getting missed in the whole running form discussion is that form is only one element of what makes a good, healthy runner. If we look at the majority of the running population (not just the elites who are probably outliers on the curve) many runners run poorly because they move poorly in general. We live in a very sedentary culture. Many runners get into the sport as adults in their 30s, 40s, 50s or older. Aging and years of abuse or underuse have made them weak, their joints restricted and their muscles are full of knots (trigger points).

Primitive man may have not run in shoes but he was also probably a lot

stronger and more agile than modern, industrialized man. With no cars or

machines to do heavy labour we had to move more. Living day to day was a workout. So to me the solution isn’t as simple as running barefoot or in minimialist shoes (though both can be great tools if used properly).

Trying to change form without also working on any strength and mobility deficits will at best limit the benefits or more likely, increase the risk of injury. Form work needs to be part of a comprehensive training program. Strength training, joint mobilization and trigger point release need to accompany any technique work. After working with hundreds of runners over the past decade I can say the majority had restricted ankle and hip mobility which will affect their form. If they simply tried to alter form without improving the joint and muscle function in these areas it probably wouldn’t have worked well.

(A reduction in running volume is also prudent during the initial period of change.)

That was an amazing post. I don’t know how he can justify saying we “evolved” to run in shoes when the modern cushioned running shoes have only been around for less than a hundred years! Great post. Thank you for spending your time writing about all of this stuff.

I call shenanigans on the comments that there is no evidence that being higher off the ground leads to instability and sprained ankles. I very rarely wear anything with a heel because I constantly roll my ankles the farther away from the ground I am. I have discovered that I am a klutz with shoes on, but my coordination and balance improve exponentially with shoes off. Unfortunately I am easing back into running after a long break, plus I am overweight, so for the moment I need some cushion for the asphalt. Looking forward to start easing some minimalism into my training when I am ready.

Great post.

I think that some things that we need to consider about running barefoot.

When the human body evolved to run he didn’t run on asphalt or on concrete. And the life expectancy was much shorter. Our legs where not design to run more than 40 (?) years…

IMO shoes need to be cushioned. Heel hight is something else…

Here is food for thought…..Maybe we changed our stride anfd gait as an adaptation or as a response to our environment. Not our social/physical environment, but the foot’s environment – our shoes. We can blame our social environment in part for that, firstly – fashion for one and secondly; the ongoing technological quest initiated by the marketing departments of the shoe companies to reduce injury, that may be they were in part responsible for causing (Good strategy – create a problem – then market and sell a proposed solution to the problem).

The longer stride issue and it’s proposed link to injury comes naturally as we remove the biofeedback and proprioceptive input that puts our body into an injury prevention mode. For runners the injury prevention mode is notably a shorter stride and a midfoot strike. This style of posture and gait better utilizes the energy control capabilities of the muscles spring properties in eccentric contraction, reduces shearing and non-uniform compression on joints, and takes better advantage of the osseous matrix that makes up the core of our supporting long bones. There is a plethora of injury prevention advantages to making that change in stride. The one stimulus that may have been responsible for us originally adopting that shorter stride is biofeedback and proprioceptive feedback from our environment. Our footwear insulates against that and possibly then removes our body’s desire to move towards the less injury causing stride. The very a physics of footwear also tends to cause our stride to be lengthened, and the distal inertia caused by the swing foot and its added mass also may logically lead to the longer stride. Anyhow the move to lighter minimal shoes with some type of biofeedback interaction with the foot’s plantar surface may naturally lead to a change in stride length and a midfoot strike – thereby removing a runner needing to consciously re-train their gait – anyhow, just some food for thought. Get minimal and get some proprioceptive stimulation.

Epic, simply epic!

Still, like most articles on running, the “ground hypothesis” is that the runner is already running, and we simply want to figure out how to run “better”.

We first must agree about what “better running” means. Does it only mean faster? Or farther? Or maybe with fewer injuries or less pain? How about with greater comfort and joy? Clearly, depending on the person, the definition of “better” can change with time and circumstance.

Let’s instead look at the completely unsuccessful runners, the “broken” runners, folks who haven’t ever learned how to run without pain and injury, or with any comfort at all. What do we tell them? Where do we start?

I’m such a person. I quit running for 20 years before triathlon made me want to try again. And then I broke, just like I did 20 years before. Changed things and tried again. And broke again. Changed more things. Broke AGAIN!

I’m now running with more comfort and joy (yes, like the Christmas carol) than ever before in my life. And I didn’t stumble upon this until I turned 54 (my present age).

What is SAFE and COMFORTABLE running? What is the “minimal” stride we can teach to ALL non-runners to help them find success? (And comfort and joy, of course.)

I have my answer, and it also seems to work for a few other “miserable” runners with whom I’ve shared it.

Do you know what it is? What do you think are the most important components of a stride that can provide comfort and joy to ANYONE who is medically capable of running? And in a way where the surface and/or shoes just don’t matter so much?

Hint: That Kenyan kid in the video has the right idea.

-BobC

http://BobIsATriNewbie.blogspo…

I find it incredible that they talk about “evolution” that heel raise would be better. Certainly, if the western shoe tradition is to have heels in all shoes, the body will adapt, like shortening the Achilles tendon. Running with heavy heelstrike (which raised heel leads to) does not utilize the the calf muscle as much as forefoot/midfoot, and thus the body adapts, the calf muscle and achilles tendon gets weaker.

So what happens when you at grown up age suddenly remove heel lift and switch running technique from heelstriking to forefoot? Sure it will seem like forefoot running is poor because the load on calf is too high – the body has not been adapted to it! It probably takes 2 – 5 years before the body is *fully* adapted to the new running technique, and preferably you should use zero drop minimal shoes in your regular life too, not just in running.

For people who like western fashion with raised heels etc and are not prepared to get into running seriously and actually change shoe habits throughout, then heelstriking with heel lift shoes may very well be “the best” way to go. But if you are really into running and foot health, then I’m quite sure that zero drop and midfoot/forefoot is the way to go, although we cannot say it’s a scientific fact, at least not yet.

When you never feel pain, then your running form is good! LOL

Just one more comment, it is rather typical that shoe manufacturers only refer to barefoot running, rather than minimalism. They try to make the picture that either you run 100% barefoot, or you use their overly cushioned high-heeled shoe. I’ve seen this many times. The interview with Simon Bartold is just one of many examples.

By leaving minimalism out of the picture they don’t need to answer the question “maybe it would be better with a little less cushioning, heel lift etc?”.

Good point – it doesn’t have to be black and white, and it’s nice to

see big companies like New Balance and Saucony exploring that middle

ground in a meaningful way.

Hey Pete…you know you and i are in agreement on most things and i advocate running in minimal shoes as fervently as the next guy, but I do have a couple of thoughts just to play a little devil’s advocate…

1) Do you think running form involves other parts of the body besides the lower limbs? It seems like most, if not, all of the focus these days are on footstrike and shoe selection, but i would argue that other factors beyond foot placement and degree of heel lift contributes to “proper form” when running. Off the top of my head, i can think of hip angle/tilt, body posture, arm carry, etc as other contributing factors. Maybe because you’re mainly a shoe guy and this is a shoe blog so you’re concentrating on it here, but personally, I think proper running form doesn’t just involve feet and shoes or no shoes.

2. “Improvement in biomechanics” to the scientist in me involves energy expenditure, which can be objectively measured in laboratory setting. We do this all the time with lab animals when we study how motion affect different physiologic parameters. So if a particularly running form or running in a particular running shoe leads to improvement in biomechanics, that would mean that the runner running in one form or type of shoe vs another would expend less energy running for a particular time at a particular pace in an ideal setting. Of course these types of experiments would never be done, but that’s what improvement in biomechanics means to me.

3. One final point. Why do we always use Kenyans as the “ideal” that we should all strive for? I never quite understood that. Yes, they were born and raised running with no shoes and yes they are the fastest, most efficient runners in the world, but does that mean that their running style/form is ideal for US? We are not born with the same genetic makeup as they are. Anatomically, their bone structures, muscle composition, proportion of brown/white fat, etc, are slightly different and they are evolved to adapted running in their environment. We are simply not. Even if we run with exactly the same form as they, we will not harbor the same results. What works for them may not necessarily work for us, with our genetic makeup, in our environment. That’s why i’m always hesitant to draw conclusions based on observations about how Kenyans are brought up and how they run as the “model” upon which we should adopt. Perhaps that’s why running barefoot does not work for many of us and gets many people injured. It may not just have to do with speed of transition…there may be subtle biological differences which make it harder/impossible for some to adopt that style of running because of our genetics.

Just some food for thought. That’s all. Great post, as always Pete. I enjoyed it very much.

Lam,

Some thoughts:

1. I have discussed other aspects of form, in fact in my recent post on

elites at Boston I compared posture and arm carry among all of them. What I

find is that those factors vary a lot even among elites. I’m also less aware

of research on those factors as they relate to performance – it may be out

there, but I am not familiar with it, so I stick to what I know best.

2. Improvement could be interpreted in terms of efficiency, but you could

also think in terms of speed or injury risk. A sprinter for example doesn’t

need to be aerobically efficient like a marathon runner, they just need to

get from point A to point B as fast as possible. There have been many

studies looking at oxygen consumption of runners as you suggest, but many

are hard to interpret, and shoe companies rarely ever published “proprietary

data.” It’s also worth noting that the most aerobically efficient stride

might not be the best in terms of minimizing injury risk. Just because

something improves performance doesn’t mean it is good for you (think

steroids). For the runner who just wants to log miles and doesn’t care about

performance, improved biomechanics could simply mean the running form that

makes it least likely that they will get hurt while still enjoying what they

are doing.

3. Regarding Kenyans – easy answer is they are the only ones for whom we

have slow motion video of people running who have never worn shoes. As

children, they are probably adapted to running in an environment that

probably includes little cement or asphalt, yet they do quite well on those

surfaces as adults. We grow up running on cement and asphalt, so one would

think we should be better adapted to those surfaces. I agree that there are

biological differences among humans that can play a big role in our running,

and I don’t think there is such a thing as the one ideal form that every

runner should emulate. At the same time, I find it hard to believe that

forcing what seems to be a major biomechanical change via overbuilt modern

shoes doesn’t have some potential negative consequences. There have to be

some things that should be emulated by all human runners, we just need to

figure out what those things are.

Pete

Excellent article, I personally go for the Vibrams when running but it seems like good form is what matters most when it comes to improving and getting less injuries.

-Bill Lee

link to runfaster360.com

Thanks for this article! I just started the couch to 5K program and have been experiencing quite a few aches and pains…hopefully these tips will help!