I open this post with an illustration of the Galapagos Finches and their variable beak anatomy (illustration by John Gould) – my reason is to emphasize a point. As an evolutionary biologist, I’ve spent much of my life studying anatomical variation, and I think it’s sometimes easy to forget that we humans are animals just like any other. As such, we also exhibit anatomical and physiological variability just like any other species does. Variability is the raw material upon which natural selection acts, and without it these finch species would not have evolved variable beak anatomy to specialize in different food niches, and we humans would not be the exceptional distance running species that we currently are.

I open this post with an illustration of the Galapagos Finches and their variable beak anatomy (illustration by John Gould) – my reason is to emphasize a point. As an evolutionary biologist, I’ve spent much of my life studying anatomical variation, and I think it’s sometimes easy to forget that we humans are animals just like any other. As such, we also exhibit anatomical and physiological variability just like any other species does. Variability is the raw material upon which natural selection acts, and without it these finch species would not have evolved variable beak anatomy to specialize in different food niches, and we humans would not be the exceptional distance running species that we currently are.

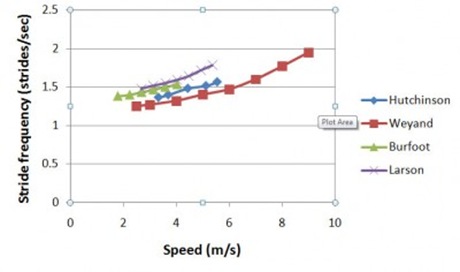

One of the points I consistently try to make here on Runblogger is that runners are highly variable. Even among elites, form is variable, as I attempted to point out in a post on gait variability in elites at the 2011 Boston Marathon (and also in this post on the 2010 Boston Marathon). As such, I don’t believe there is a one-size fits all “ideal” running form, nor do I think there will ever be one footwear option that will be best for all runners. I do believe that we evolved to run barefoot, and that barefoot is the human default, but some of us are so far removed from ancestral anatomy and physiology that running barefoot or in a barefoot-style shoe might not be a good solution. Genetics, history of past footwear use, dietary habits, and history of past physical activity (most of us didn’t grow up running 10k barefoot to school each day!) all conspire to make us the variable species that we are.

I’m constantly reminded of variability when I write shoe reviews. A shoe that I find too firm might be a favorite of a friend, and a shoe that I find plenty wide might be too tight for someone else. Any shoe review that I write is from my perspective, and should be considered with this in mind. What works for me may not work for you, and vice versa.

Another reminder about human variability comes when I read the scientific literature on running biomechanics. Non-systematic results are commonplace, meaning that different people respond in different ways to a given intervention (whether it be footwear type, a stride change, etc.). For the remainder of this post I want to give an example of variability that I think really emphasizes this point quite well.

Yesterday I was reading an article by Clarke et al. from a 1983 issue of the International Journal of Sports Medicine. The title of the article is “Effects of Shoe Cushioning Upon Ground Reaction Forces in Running.”

In a nutshell, the authors were attempting to determine the effects that running shoes of varying midsole hardness have on the forces that the body has to deal with during the stance phase of running. They had 10 runners run across a force plate a number of times in shoes with very firm and very soft midsoles (pace was 6 min/mile), and then compared the results between the two types of shoe – the goal was to compare extremes along the spectrum from firm to soft shoes since that would be expected to result in the maximum difference between the two conditions.

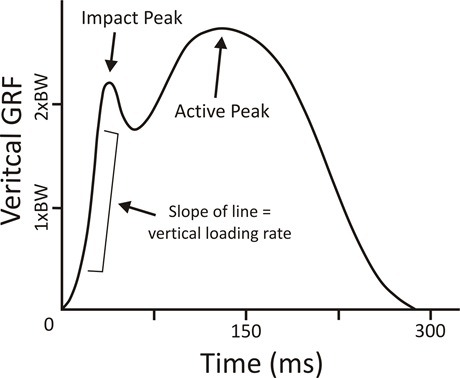

Before we dig into the results, here’s a quick reminder of what a vertical ground reaction force plot looks like for a heel-toe runner:

On the vertical (Y) axis is the value of the vertical ground reaction force as a function of body weight. You can think of this as how much force the ground is applying vertically through your foot as you run. The horizontal (X) axis shows time in milliseconds. The curve depicted on the graph shows how vertical GRF changes from the point of initial contact of the foot with the ground (time 0) to the point where the foot leaves the ground on toe-off (about 300 ms in this example). What you’ll notice in this graph is that there are two distinct force peaks. First, the impact peak is the initial force applied to the foot by the ground at initial heel contact (remember, this graph is for a heel-toe runner). Full body weight is not being applied at this point, so the impact peak is basically a function of the weight of the foot and lower leg hitting the ground. The active peak represents the force applied by the foot and supported body weight during roughly mid-stance. Notice that it is larger than the impact peak – this is the typical pattern.

Clarke et. al (1983) measured the height of the vertical impact peak, the time it took to reach the vertical impact peak (which gives info about how fast the impact force was applied), the height of the active peak, as well as a few other gait variables. Keeping in mind that the shoes being compared were at opposite extremes of the firmness spectrum, the results were quite interesting. First, and somewhat surprisingly, they found no significant difference in the height of the impact peak between the two shoes. In other words, the magnitude of the impact force was the same on average whether a runner was wearing a soft shoe or a firm shoe. The time it took to reach the impact peak was found to differ, with the softer shoe delaying the impact peak by about 4 milliseconds on average (this means that the softer shoe tended to slow the application of the impact force, which is probably a good thing). Third, they found that the active peak (they refer to it as the propulsive peak) was significantly higher on average in the softer shoe.

In summary, just looking at the average results, softer, cushier shoes do not appear to reduce the impact force, but they do slow down the rate at which the force is applied to the body (much as a boxing glove would slow the rate at which impact is applied to your hand if you punched a brick wall). Softer shoes also result in higher forces at mid-stance – the authors suspect this might be related to greater heel penetration into the midsole during stance, allowing the calf muscles to exert greater propulsive force under the forefoot on pushoff (if the heel sinks into the misdole under pressure, it is effectively decreasing the heel-forefoot drop).

These results, particularly regarding impact force, seem somewhat counterintuitive – runners generally believe that greater cushioning will reduce the magnitude of the impact force, and heavy runners are often directed to maximally cushioned shoes for this very reason. But, this ignores the fact that our body is pretty darned intelligent, and our legs adapt their stiffness to the conditions underfoot (read this post for more on leg stiffness in running). Thus, when running in a firm shoe, our knees tend to flex more than they do when we run in a soft shoe – by changing properties of the midsole all we do is shift cushioning from one place to another (underfoot to say the knee joint), and the magnitude of the impact force stays the same.

What’s really interesting about this study is when you look at the individual results, which are quite variable. Two individuals exhibited no impact peak at all, and their results thus were not included in the impact comparisons (the authors speculated that they were midfoot strikers). Here are the results the individuals (forces are measured in units of body weight):

| Impact Force Peak (BW) | Time to Peak (ms) | Active Force Peak (BW) | ||||

| Subject | Hard | Soft | Hard | Soft | Hard | Soft |

| 1 | 2.15 | 2.33 | 21.4 | 25.8 | 2.6 | 2.67 |

| 2 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 19.8 | 26.2 | 2.52 | 2.68 |

| 3 | 2.35 | 2.15 | 22.8 | 30.4 | 2.66 | 2.72 |

| 4 | 2.93 | 2.4 | 15.8 | 25 | 3.3 | 3.33 |

| 5 | 1.82 | 2.29 | 28.5 | 31.6 | 2.82 | 2.82 |

| 6 | 2.12 | 2.04 | 25.4 | 24 | 2.18 | 2.43 |

| 7 | 2.56 | 2.55 | 25.8 | 27.6 | 2.78 | 2.98 |

| 8 | 2.2 | 2.36 | 20.6 | 21.8 | 2.82 | 2.83 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.73 | 2.74 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.87 | 3.09 |

When you look at these results at the level of the individual, it becomes clear that responses are somewhat variable. In particular, if you look at the results for impact force peak in subjects 4 and 5, they exhibit completely opposite responses to the two shoes. Subject 4 impacts considerable harder in the hard shoe, but subject 5 impacts considerably harder in the soft shoe. So, although the mean impact response between the two shoes was not significantly different, suggesting that midsole hardness need not be a consideration when it comes to managing impact force, for these two individuals it matters a great deal. What’s more, if we assume that lessening impact force is a good thing (this point is debatable as impact can stimulate bone growth, and we have no idea what threshold limits for impact might be problematic for any given individual), these two runners would require completely different types of shoes! Going even further along this line of reasoning, if our goal was to provide a shoe for these runners to reduce impact, the conventional wisdom is that more cushioning is the way to go – but, that would be the wrong answer for 50% of the runners examined here who had higher impact peaks in the softer shoes. This is what gets lost when looking at mean responses – they don’t tell you what is best on an individual level.

You can see the same type of thing when you scan the other columns. Soft shoes generally do seem to delay impact peak, but not in 100% of cases, and in some individuals the difference is very small between the two shoes. Soft shoes seem to result in a higher active peak, but again, sometimes the difference is quite small.

The point I’m trying to really emphasize here is that runners are variable, and we each have different needs on an individual level. This is why I have such a problem with the traditional approach to running shoe design. Why in the world should we expect that every individual will do best in a shoe with a 10-12mm heel-forefoot offset??? Until recently, this is the only type of shoe that has been available to most runners (and don’t say flats have always been around – they have, but generally in specialty stores and were typically not recommended for long distances and only for “efficient” runners). As recently as January of this year, I went into my local Dick’s Sporting Goods and counted 90+ running shoes on the wall – all of them – every single one – had a traditional offset. No a single racing flat or more minimalist shoe was to be found. That has changed in the past six months, but we are still a long way from really understanding how best to assign the best shoe to an individual runner. Same goes for assigning shoes based on arch height, pronation, etc. We have no strong evidence that this approach works, and in fact there is evidence that assigning shoes based on foot type is no better than assigning a stability shoe to everybody. This doesn’t mean that the approach doesn’t work for some individuals, just perhaps that it shouldn’t form the primary basis upon which we assign shoes.

We need a lot more research on how to do a better job at all of this – how to tinker with form when needed or to leave things alone, how to determine who needs lots of cushion and who doesn’t, who needs a more stable platform and who doesn’t, who’s better off ditching shoes altogether? It’s a difficult task to be sure, and right now the best approach I can suggest is a willingness to self-experiment. I do believe form and shoes play a big role in healthy running, and I don’t think that runners need fear trying different types of shoes if they do it carefully. My hope is that as more people tell their individual stories, and as more research comes to light, better advice will come with time.

Great article! I always get excited to read your next post. When I first started running, I wore mizuno’s (wave rider 11 or 12?) and over a year i went from a 9:30min/mi to about 7:30min/mi. I then switched shoes (to these Asics that I don’t remember now), and I had awful shinsplints and kept changing shoes for a year and a half until I found these bulky New Balance shoes that worked. Unfortunately, during this time period i became much slower and gained some weight. Now I’m in the NB 993s and back to almost 8min/mi. I really want to start going lighter for my shoes, but I’m wondering how I should begin focusing on my form while I run? Any articles on that? I figure I’ll work in form before I try to go more minimalist.

Pete, great post! I agree that a craving for cushion can counter-intuitively produce heavier landings. I did read a study somewhere along the way that indicated runners also produced lower impact forces in old running shoes with packed-down dead cushioning. It’s a variable word out there! Having watched my friend Mark fit runners into shoes in his store you definitely have to see the runner actually RUN in a few different pairs before making a recommendation on what looks, sounds and feels right for an individual.

Great Article, well done for the research and for the thoughts.

In my opinion there is one thing what everybody should consider. What is anatomically correct ? That is when we stand on our feet without an elevated heel platform. Running should be done on the same way, without a chunky heel.

Unfortunately it is true that a lot of people broke loose very far from this. 30-40 years in high heel shoes would make transition very hard. But still, I think with good education and gradual transition, it is possible to place back not only running but your whole life into a “flat position”. Someone can make it in 4 weeks, others may need 4 years.

It would have serious impact on running performance even in high quality runners. As all the studies suggests the more you can engage the “human springs” during running the easier it becomes. And if one made a successful transition, that is the time when they could play with sole thickness and sturdiness depending on race distance, surface, elevation, temperature.

Until there are so many runners, with very little education on correct form, every kind of shoes will be sold in the market. That is why I like the approach of Inov 8 shoes. They have all sorts of shoes for the transition. Starting with a 12mil offset, down to 9,6,3,0 than in the zero heel to toe offset there are the bare type of shoes with the wide toe-box. There are shoes with a bit of an aid “Fascia band” others have no support system at all.

Choose what you want, then follow the line down to the bottom.

At the moment there is no law or standard in the “big book” of running to know which is the “correct running” form. Until it is not taught in schools as a standalone subject, people will run with heel strike, toe strike, forefoot midfoot strike.

Everyone has to make it’s own choice and we have to leave people to do so, and not force anyone to go barefoot bcse now that is the trend. When the individuals realize that something is not good, and in order to stay healthy it has to be changed, they will do their own research and do the appropriate steps. Until then, with a lot of advertising and clinics, companies and educators can try to grab the attention of keen runners, to make their life changing decision.

http://evolutionexpress.blogsp…

I’m not sure this post or paper does a good job at emphasizing the point you are trying to make. Comparing each subject to one another in the same shoes would do more to emphasize variability. I don’t think any research needs to be done between soft and firm shoes as the emphazise needs to be on form. I believe their is no debate on what is best for everyone. Short quick strides, with a midfoot-forefoot strike. I would imagine if these same subjects were instructed how to land properly on their midfoot, impact forces would be lowered in both types of shoes. I would also guess that impact forces with a midfoot strike in a firm shoe would have overall the lowest impact force. As someone with a masters in biology, I understand why you included the finches but those are 4 different species and even a couple different genera, who evolved different beak shapes to specialize in feeding. We are all one species trying to accomplish the same goal so I believe that their is one “best” form with possible slight variations. Maybe everyone can’t start out wearing a pair of VFF or barefoot but I don’t think heal striking in a 12mm off-sett shoe is healthiest most efficient way for anyone to run.

Those four species/genera of finches would not exist if intraspecific variation did not exist in the population(s) that gave rise to them. We humans deal not only with intraspecific variation due to our genetics, but also a huge amount due to environmental causes like past/current shoe use and activity levels. In that sense we are quite different than a typical wild population. For a woman who spends 60 hours per week in high heeled shoes and is not going to change that habit(yes, they do exist and have been studied), a 12mm heel lift is probably quite reasonable.

I agree with you on intraspecific variation but humans are no longer at the mercy of natural selection at least in terms of physical traits being selected for i.e. strength, speed and even intelligence as those finches were. We are getting a bit off topic however. A woman or man who spends all day in a heeled shoe is making a conscious choice to do so if they are not willing to make a change, “natural” running may not be best for them but that doesn’t mean that if they were to make the transition to level shoes landing on their midfoot, that they wouldn’t run more efficiently with less impact forces. I guess the point I’m trying to make is that just because some people are more at risk for injury switching to a midfoot strike, because of their lifestyle choices, does not mean that their isn’t one best running form. I do agree that their will be variations on running form from individual to individual but not to the extent that a heel strike is best for a particular individual.

If we are no longer at the mercy of natural selection (which is debatable, but likely true at least in regard to running ability), then variation will be even more pronounced as there is little to cull the herd so to speak. Disadvantageous variants are less likely to be selected against, and people who can’t run well due to anatomical or physiological variants are not hampered by it since their life does not depend on being able to run. Much as I might like to, my physiology will never allow me to challenge Ryan Hall in a marathon, and I’ll probably never have the endurance and sheer ability to tolerate tissue stress that a guy like Dean Karnazes has.

Even Lieberman in his study of Kenyan kids who have never worn shoes found some who heel strike. In my experience with biology, if there is a plausible exception to any rule, it probably exists in nature. There may be an ideal that is best for most, but the realistic view is that the vast majority of people are going to wear some kind of shoe, and that in and of itself makes any attempt to promote a single ideal problematic. Much as I might like my kids to be barefoot all the time, I live in a place where it’s really cold in the winter (as did my nordic ancestors), they do have to wear shoes to school, and the school is only a half mile from home so they generally don’t have to run to get there on time. So, we do the best we can with the options out there, but they are growing up in a very different environment than say Haile Gebreselassie did, and an even more different environment than that of our Homo erectus ancestors. Our body in general might not have changed much over the past 2 million years, but our environment and behavior has changed

a lot, and it’s important not to forget that.

Given this, I think each person needs to find the approach that works best

for them on an individual level given their anatomy, physiology, shoe usage,

etc. There are helpful things that can guide us – like mechanisms to reduce

impact, improve strength and stability, etc., but there is no one form or

shoe that will work for every person on this planet. The real world is

messy, and our ideals do not always apply.

This is why I will follow your blog for as long you keep it. You always provide great explanation and insight and I agree with everything you just stated. I agree that because of a lack of natural selection for our physical traits that their will be greater variability but also it would be unlikely that multiple forms would ever arise like the finches.

I am curious about the heel strikers of the Kenyan children as Ii reminds me about the picture you put up with the Patrick Makau heel striking in his world record race. I often hear people talk about elites running a certain way but does that mean the way they run is the best or even the best for them. Is it possible that Makau could have ran even faster if he didn’t heel strike? Was he running the most efficient way possible? Are the Kenyan children that heel strike, running the most efficient way for them? Just because they have never had shoes on their feet, does that mean they naturally run the most efficient way?

Thanks Theo – all great questions, and I wish I had the answers! Makau is wearing the Adidas Adios I believe, which has a pretty traditional offset for a road flat – would be very interesting to see him run barefoot or in something flatter just to see what would happen. Likelihood of that is low of course given his sponsorship, but Adidas is making a new, lower profile flat called the Hagio and it will be interesting to see it on the feet of some elites. These kind of questions are what keep me going.

great to read a thoughtful discussion comparing running shoes that does point out too many assumptions are being made – on both the establishment side of things and the barefoot side of things. Personally I think it’s great to listen to different ideas and insights and weigh them against your own running experience, rather than chasing some grail of perfect running that might just not be your perfect running.

At the Hoka One One blog, we’re hosting some video interviews with running legend and Boulder Running Company co-owner Johnny Halberstadt, with a couple on biomechanics and minimalism to come. Please drop by and have a listen – very interesting dude.

http;//http://www.hokaoneoneaustralia.wordpr...

We’re anti-establishment and not entirely minimal, so there’s something for all y’all. ; )

Hey Pete: Another great one, but a few questions for you.

1) For the Clarke study was there any indication on the runny style of the test subjects (heel strike, mid foot, angle of knee flexion)?

2) If all of the test subjects were in the same shoes, could the results they were seeking be manipulated by form?

Thanks Pete!

Pattoin

Unfortunately they didn’t record much kinematic data beyond stance time, but they speculated that the two subjects with no impact transient were midfoot strikers and the others heel-toe. So yes, I suppose form manipulation could change things – it would be interesting to see how those two very divergent individuals would respond if they ran barefoot.

Pete said: ” I don’t believe there is a one-size fits all “ideal” running form, nor

do I think there will ever be one footwear option that will be best for

all runners. I do believe that we evolved to run barefoot, and that

barefoot is the human default, but some of us are so far removed from

ancestral anatomy and physiology that running barefoot or in a

barefoot-style shoe might not be a good solution.”

I have a couple issues with the above statements, in terms of needed clarifications:

1. We may be ‘natural’ barefoot runners, but I believe that applies primarily to running on ‘natural’ surfaces. When concrete and asphalt are added to the equation, what’s ‘natural’ may need to go out the window. We have not yet had time to evolve to run on hard artificial surfaces, though there definitely a relatively very small number outliers who can indeed run quite well barefoot on such surfaces.

2. There may not be an ‘ideal’ form, but we must make it clear that ‘ideal’ in this context means ‘optimal’ in terms of both speed and efficiency for longer-distance or endurance running (excluding sprinting), There is a simple ‘common’ running form that all endurance runners may use with total comfort and great effectiveness, even in the presence of significant physical limitations. No, it may not be ‘ideal’ from an efficiency or speed perspective. Think of it as a ‘beginner’s’ form. The search for an ‘ideal’ can easily obscure the ‘greatest common denominator’.

I have my own description of what such a general stride looks like (I use it daily). If you were to define or design a stride that your aged grandmother or obese uncle could use, or friend with badly degenerated discs (such as myself), or partner with chronic running-related injuries could use, what do you think it would look like?

-BobC

Bob,

1. I agree to an extent, but I think it’s the combination of both “hard” and “unvarying” that is at issue, and perhaps moreso the latter than the former. I can run fine barefoot on asphalt, in fact I find it quite enjoyable, and most barefoot runners would agree that smooth asphalt is the preferred surface to run on.

2. I’d guess something along the lines of a shuffle run with minimal flight time? That being said, I’m pretty sure my grandmother’s severely arthritic knees would prevent her from doing even that!

As always, a really nice article, Pete. One thought,

tangential to your main point but here… The impact peak is indeed just the

weight of the foot hitting the ground. If you were to model the body mass on

top of a spring (a leg) you would see something that looks just like the active

peak without the impact. But if you add to that model a small weight at the

bottom of the spring, you would see something that looks much like an impact force

preceding the active peak. The important thing with respect to injury, is what occurs

at the tip of the active peak – that is where joint torques and forces are

greatest and relate to where injuries (like osteoarthritis) occur.

Thanks Casey – makes sense, though I’d guess the degree of knee extension at contact might have some influence on how much the impact force is mitigated by the leg spring and an extended knee could make the impact force more problematic?

To continue with this evolutionary/philosophical discussion, I thought you might enjoy this article:

CULTURE ON THE GROUND: the World Perceived Through the Feet

TIM INGOLD 2004

available here:

link to nyu.edu…

It explores the role hand-tools vs feet-walking/locomotion played in evolution…it goes on to some cross-cultural analysis of walking gaits, among other things…the develop of distinctive ‘form cultures’

from the Culture on the ground: “The goose step is only possible on the artificially monotonous surface of the parade-ground”

What does ‘natural’ running form mean, considering the abundance of ‘artificially monotonous surfaces’? (e.g. roads, golf courses, exercise trails).

Human variability + surface variability -> form+surface homogeneity

An effective training plan focuses on both skill and

energy. Skill comes from proper form and

efficiency training. Energy development comes from balancing out speed,

strength, stamina, and threshold workouts.

For readers who want to know more about how better form can

help improve their running, this video series will help you.

Running Form Video Series>>>> http://www.TransFORM-Your-Runn…

Courtesy of Coach Ken at 5 Speed Running

WIth all this talk about evolution, nobody asks the question: why do we even have a pronounced heel then? If forefoot striking is the “best” way to run, we should be like cats and dogs and walk around without our “heels” touching — the heel going the way of Wisdom Teeth. Since we have still have prominent heels, my guess is that it is somehow beneficial to use them when we run.

Walking = heel toe, running is a different gait.

—-

Pete Larson’s Web Links:

My book: Tread Lightly – link to ow.ly

Blog: https://runblogger.com

Twitter: link to twitter.com

Facebook: link to facebook.com…

So our heels make it clear that evolution has designed us to walk rather than run, so all the talk about the “natural” way to run sort of becomes moot: even though we can run, it’s not our primary evolutionary design.

We can do both very well, in fact we run long distances better than just about any other animal on the planet.