Image via Wikipedia

One of the difficulties that we face in trying to determine how to describe “proper” running form (if such a thing even exists) is that data on what runners did prior to the advent of modern, cushioned running shoes are hard to come by. Whereas videos of runners prior to 1970 or so are available, most are not filmed at a high enough speed to accurately analyze the more rapid motions that occur during the running stride. In particular, the question of how runners typically contacted the ground in the days before the cushioned shoe are difficult to address.

In 1964, a fascinating study by Toni Nett was published in the journal Track Technique. The paper was actually a translated English synthesis of an article published previously in a 1952 issue of the German publication “Leichtathletik,” and in it Nett reports the results of an analysis that he conducted on foot strike patterns of elite runners from the 1950’s (included in his sample was the great Emil Zatopek). Nett was able to film these runners in high-level competitions at 64 frames/second – not particularly high-speed video by modern standards, but fast enough to get a decent idea of what the feet of these runners were doing. His reason for doing this was to “throw light on the problem of more than 50 years standing: how the foot is planted.” He indicates that there had long been a polarized debate among coaches, with some insisting that “all runners at all distances plant the foot heel first,” while others insisted that “the foot is planted exclusively on the ball by all runners at all distances.” Nett was interested in determining which of these viewpoints was correct, or whether perhaps foot strike varied by event/distance run (i.e., speed).

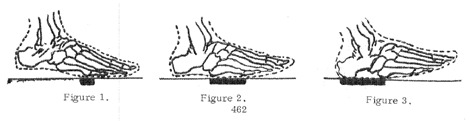

Nett filmed runners in events ranging from 100m to the marathon and reported his results. He observed the following (image below is from Nett’s Track Technique paper):

1. All runners, regardless of event, initially plant the foot at the outside edge.

2. 100m and 200m runners initially contact high on the ball of the foot, including the joints of the little toe (Figure 1 above). 400m runners contact slightly further back from the sprinters. Nett calls this the “active or dynamic ball plant.”

3. 800m runners typically land along the length of the 5th metatarsal, with the heels and toes slightly off the ground at contact (Figure 2 above). Nett calls this the “metatarsal plant.”

4. 1500m runners land in a manner similar to either the 800m runners or in a manner similar to marathon runners – in other words, this is something of a transitional distance (Figure 2 or 3 above).

5. Runners in events ranging from 1500m to the marathon contact “with the outside edge of the arch between the heel and metatarsus (Figure 3 above).” Emil Zatopek was included in this group. Nett calls this the “passive or static heel-metatarsus plant.” He found only one exception to this – one runner landed on the ball .

6. After contact, the heel touched down in all runners filmed, even sprinters.

One question that arises from these results is how to translate the above categories observed by Nett into modern foot-strike terminology? Based on the drawings above, I would suggest that the sprinting foot strike (Figure 1) is what we commonly refer to as toe running, or an extreme forefoot strike. The 800m to 1500m strike is what we now refer to as a forefoot strike since the heel does not make contact upon initial footpplant. The 1500m to marathon strike is probably what we now refer to as a midfoot strike since both the heel and base of the 5th metatarsal make contact simultaneously (this category might also include mild heel strikes, but it’s hard to tell from Nett’s descriptions). The base of the 5th metatarsal is located about midway from the heel to the base of the little toes, and if you try to place your foot down so that it contacts at both the heel and this location simultaneously, you will see that contact is roughly along the entire outer margin of the foot.

Based upon his observations, Nett makes the following conclusions:

1. The sprinting foot strike allows for a fast pace, but is “rather energy- consuming.”

2. The “metatarsal plant” is intermediate in terms of strength requirement and is thus suitable for middle distances.

3. The “static heel-metatarsus plant” is an endurance gait since it requires the least energy per step, but it is not suitable for high speed.

Nett emphasizes that foot-plant is correlated strongly with pace, and he recounts his observation that when sprinters run in a more long-distance situation, they adopt a foot plant like that seen in Figure 3 above. Because of this, he cautions us to not make conclusions on the foot plant of individuals based on still race photos since a middle distance runner sprinting to the finish line will adopt a sprinter’s footstrike (he is a believer that only high-speed video can truly provide an accurate assessment of foot strike – personally, I agree).

Nett goes so far as to say that “foot-plant evidently follows laws that lie outside the person, that lie in the rate of running speed.” In other words, foot strikes that he observed were so consistent in the different events that the speed at which an individual was running was a better predictor of foot strike than any type of inter-individual variation. In contrast, other aspects of running form (trunk, arms, head, etc.) were so variable that “not even remotely can so uniform a picture be obtained.” He considered these other factors to be elements of individual style rather than related to speed or the event being run.

Based upon all of this, Nett concludes that “shifting (of foot plant) the runner does unconsciously; but he correctly adapts it quite instinctively and reflexively to the distance as related to the pace.” Thus “arbitrarily interfering with the foot-plant of top-notch runners might therefore, be wrong because (sic) unsuitable.”

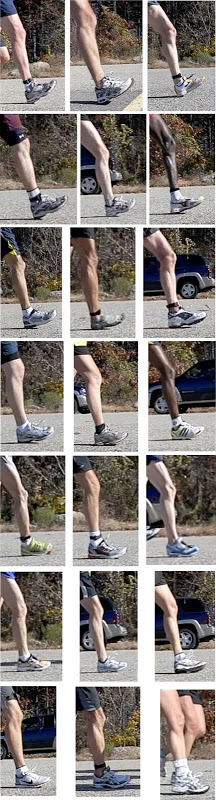

I find all of this fascinating because it provides a window into what runner’s did before the advent of the modern running shoe. Unfortunately, Nett was filming elites of the day, and it is difficult to compare these individuals to modern recreational runners. However, it does not seem that Nett observed any of the overstriding, massive heel strikers that are so commonly observed in modern races (even sometimes among very high-level runners). As an example of the variation seen among modern runners, take a look at the photo below showing foot strikes of runners from mile 20 of the 2009 Manchester City Marathon (yes, that is a Vibram Fivefingers heel striker – he’s a friend of mine – his quads locked up and he had to stop and walk most of the last six miles after this photo was taken):

Clearly we now see a lot of variation in foot strike, but we still have very little idea of how this variation might relate to either performance or injury risk. We also have little idea of how much of a role footwear plays in determining footstrike, as it is clear from the above that we see all types of foot strike variants even in similar types of shoes (though the vast majority of modern runners do land on their heels with no simultaneous metatarsal contact – a category not observed by Nett).

As far as the role of speed/event, the following video of elite female milers from the 2010 5th avenue mile shows that most are either midfoot or forefoot strikers:

Whereas this video of elites from the 2010 Boston marathon shows a mix of different types of footstrikes:

I will point out that I don’t think the reason that modern recreational runners are overwhelmingly heel strikers is due to their slower speed – I do think footwear is a big part of it. As one example, here is Paul Tergat on what appears an easy jog – he’s clearly not heel striking (n =1, but interesting nonetheless):

And I’ll finish with this great video of Herb Elliot from 1960 – just because it’s a thing of beauty:

Interesting analysis! I noticed that I tend to strike towards that outer edge of my foot-all my shoes (especially flats for workouts) tend to be worn on the 5th metatarsal.

Owww…..my shin splints are coming back after seeing the VFF heel striker. Herb Elliot: lands right on midfoot (maybe towards the front a bit), he is not overstriding, he lands with his foot almost behind his CG, great posture, and his foot is not on the ground long. Beautiful. Any Adebe Bikila video? Good writing Pete.

Go to 1:15 of this video for Bikila:

link to youtube.com…

Wow, to me he seems to be a slight heel striker in shoes.

Yes, I would agree. But, his form is excellent, so don’t think it matters much.

Thanks for that video on Elliot – that’s just tremendous!

Fascinating research as always Peter.

Great article. Speed, cadence, distance, and shoes all make a difference. The thing that was left out was running surface. If you look at the first picture in your article you will notice the uneven surface of the track where it has footprints in it. I run on horse trails with smoother surfaces than that track. I find it just about impossible to maintain good balance on uneven surfaces when landing on my heels. Even during long slow runs on horse trails I tend not to land on my heels. On concrete sidewalks or roads I will land on my heels most of the time unless I am wearing minimal shoes that don’t have cushioned heels and I maintain a high cadence. Landing of my forefoot allows me to maintain good balance when running on uneven grass through the park or on trails. I tend to avoid grass or trails when running in high heeled pavement pounders.

“I will point out that I don’t think the reason that modern recreational

runners are overwhelmingly heel strikers is due to their slower speed – I

do think footwear is a big part of it.”

I think this point goes against most of that which precedes and is the weakest statement in an otherwise very insightful and interesting article. The fact that almost all the elite athletes in these videos are running quickly and forefoot/midfoot striking and all the recreational runners running a lot slower are landing further/significantly further back, cannot be ignored. I think the Tergat video especially supports my belief that form has a lot more to do with landing on the forefoot than the size of the heel and shoe.

But this is just conjecture aswell. A study combining both elites and non-elites in varying levels of shoe and surface running different speeds needs to be made to lend significant weight to those of us that believe running in more minimalist shoes is better.

You have to keep in mind that these elites are almost always wearing

racing flats, and recreational runners until recently rarely did.

Shoes are a confounding factor when it comes to associating foot

strike and speed.

I know this was before the modern atheletic shoe, but did folks in the 50s have different shoes for different events? The sprinters in the photo appear to have what we would consider minimal shoes. Did distance runners use harder soles? Most non-atheletic shoes of the time had a hard leather sole.

I don’t know. But most of the casual shoes even back then had

constricting toe boxes and raised heels. So, even if they were racing

in very minimal shoes, most of them probably had feet adapted to shoes

similar to casual shoes of today.

That Herb Elliot video is indeed amazing. Among other things, his recovery kicks his trailing foot almost all the way up to his glutes. I mean, holy hamstrings!

Its a really interesting study that gels with my ‘gut feeling’ about my foot strike at various speeds. At a sprint im up on my toes and as the speed reduces the strike moves further and further back along the foot.

Pete whilst i wouldnt suggest that speed is the only or even the primary cause of heel strike in recreational runners i wouldnt rule out that it could be a significant factor.

if you watch the video’s of the elite men and women you will see that during the flight phase their leading leg acting like a pendulum actually extends quite a long way past the vertical, then the body and knee ‘catch up’ to bring the lower leg closer to the vertical as the footstrike occurs.

Take a recreational runner and the flight phase shortens up considerably, There is not sufficient time for the bodys mass to move far enough foward to bring the lower leg back into the vertical.

I cant help but suspect that the reduced ‘air time’ at the considerably slower speeds that recreational runners run at is playing a part in heel striking. I would imagine that the built up and cushioned heel exasberates and encourages this even more.

Some of us then turn to cadence control and deliberately fore-shortening our front leg swing to try and achieve a vertical lower leg at foot strike in heel raised shoes. so its possible to alter our form to correct it, but thats not necesarily the most obvious or ‘natural’ approach when your trying to eek out every scrap of speed you can.

Unfortunatly we will never be able to know what sort of foot strike a recreational runner from the pre-heel running shoe era used, the evidence just doesnt exist, but in time i fully expect that the growing minimalist runners will be able to supply us with the verifiable evidence we need.

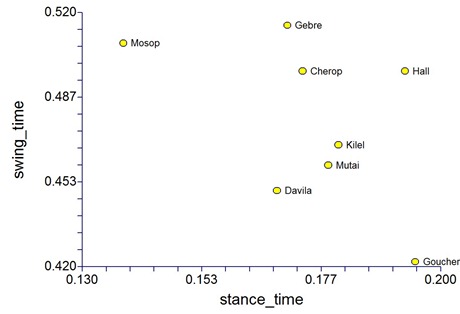

I won’t deny that speed does have some role, as the literature does

suggest that mid foot/forefoot gets more common in faster runners. It

is a bit of a chicken or egg thing though – are they faster because

they mid foot, or are they mid foot because they are faster. I have

data on marathon runners, and found that speed is not a predictor of

foot strike type, which might be part of my bias here – I’ve focused

on the marathon. Certainly, as you get to shorter races and

dramatically faster speeds, things seem change.

Another wrinkle is that I have seen runners with no flight phase at

all, yet they are clearly not walking. When you film and watch enough

runners, so see all kinds of strange stuff!

Great site, insightful perspective, keep up the good work.

Wow. If Elliot has any verticle motion I can’t see it. He looks like he’s on rollers.

I was a professional sprinter in Northumberland in 1955 and 1956 as a teenager. Now in my late 70s I am having pains in my second toe on my left foot. Could this running have been a possible cause?