Just before I left on a camping trip last week I received an email from Amby Burfoot pointing me to an abstract of a paper to be presented at the 2011 meeting of the International Society of Biomechanics. The study, titled “Foot Strike Does Not Predict Loading Rates During Shod or Barefoot Running,” was conducted by a group of researchers from Oregon headed up by James Becker. Amby wrote up a post about the study on his Peak Performance blog, and included this line: “I have no doubt biomechanists with a different perspective will find much to dissect and debate with the Oregon team. That’s what Ph.D.’s do for fun, after all.” Well, as a Ph.D. with an interest in biomechanics, I’ll take the bait and have my fun.

Just before I left on a camping trip last week I received an email from Amby Burfoot pointing me to an abstract of a paper to be presented at the 2011 meeting of the International Society of Biomechanics. The study, titled “Foot Strike Does Not Predict Loading Rates During Shod or Barefoot Running,” was conducted by a group of researchers from Oregon headed up by James Becker. Amby wrote up a post about the study on his Peak Performance blog, and included this line: “I have no doubt biomechanists with a different perspective will find much to dissect and debate with the Oregon team. That’s what Ph.D.’s do for fun, after all.” Well, as a Ph.D. with an interest in biomechanics, I’ll take the bait and have my fun.

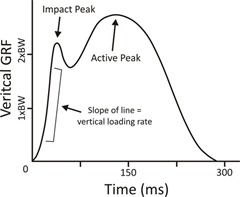

Basically, the researchers had 11 habitually shod subjects run across a force plate either in shoes or barefoot, and recorded the resulting ground reaction forces. In particular, they calculated vertical loading rate, which is essentially the speed at which the foot initially impacts the ground. Loading rate is of interest because some studies have suggested that it might be linked to a higher incidence of injuries like stress fractures. They also calculated a variable known as foot “strike index” (SI) for each individual – this is basically a value from zero to one that tells you at what point from heel to the tips of the toes the foot makes initial contact with the ground (a value of 0 would be far back on the heel, a value of 1 would be at the tips of the toes). Their goal was to determine if strike index was a good predictor of the vertical loading rate. In other words, does the location at which the foot makes initial contact with the ground influence the speed with which the collision occurs.

The study concluded that stride index is not a good predictor of loading rate for either shod or barefoot runners, though the latter relationship was nearly significant with a p-value of 0.06 (a p-value of 0.05 or less is typically considered a significant result). The authors also pointed out that most of the runners adopted a midfoot strike when switching to barefoot, and that those who continued to heel strike when barefoot experienced an increase in vertical loading rate. The latter is this is why I don’t agree with Amby’s statement that “the University of Oregon team will report that their lab testing doesn’t support the notion that forefoot striking lessens the “instantaneous load rate” vs. rearfoot running.” What it shows is that rearfoot running in cushioned shoes doesn’t differ from midfoot/forefoot running when barefoot – those who continued to rearfoot strike when barefoot experienced increased loading (as was also shown by Lieberman et al., 2010). In other words, shoes allow us to rearfoot strike with a loading rate similar to that seen when we forefoot strike when barefoot, and loading rates of both are lot less than if we were heel striking when barefoot.

The study also failed to find a significant difference in vertical loading rate between the shod and unshod conditions, and indicated that this could be due to a large amount of inter-individual variation in response. I’d also suggest that having habitually shod runners abruptly switch to running barefoot also might be involved here, as Lieberman et al., 2010 indicated that a majority of their habitually unshod runners had lower loading rates than shod heel strikers when running barefoot (this despite the fact that the difference between the two groups was non-significant). In other words, a learning process might be involved when it comes to barefoot running and reduction of impact (see this abstract from the same ISB meeting for more on this).

The authors conclude their abstract with the following:

“Based on this small sample, it appears foot strike pattern does not predict VILR under shod or barefoot conditions, and changes in VILR when one switches from shod to barefoot, or from RFS to FFS, are highly variable between individuals. Thus, generalizations regarding the benefits of one foot strike pattern compared to another should be interpreted with caution.”

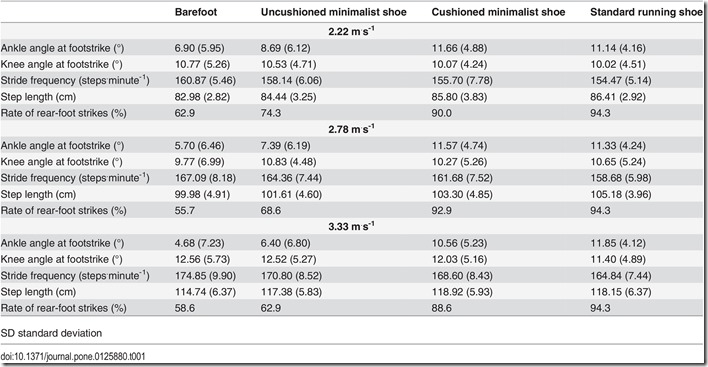

My take is that this abstract seems to provide support for a number of observations that exist in the literature. In particular, Lieberman et al, 2010 also showed that heel striking in a cushioned shoe results in a vertical loading rate that does not differ from that of individuals who forefoot strike when barefoot (look at Figure 2b from their Nature paper). However, what does differ is the fact that limbs in the different conditions likely handle the impact loading in different ways. A number of kinematic studies have shown differences in things like joint angles and limb positioning at impact, including an abstract of a paper by a group from South Africa to be presented at the very same meeting as the study under discussion here. It’s important to remember that ground reaction forces simply describe the reaction of the ground to forces applied by the body via the foot. These are external forces, and thus don’t describe how those forces are applied internally to individual muscles, bones, joints, etc. Thus, the same loading rate might have a very different effect if the limb is positioned in a different way upon impact. In other words, we might not be comparing apples to apples here. What’s more, as the authors point out, footstrike is just one variable to consider, and that “other variables such as joint kinematics, joint stiffness, or muscle activity, may play a more dominant role in determining the VILR (loading rate).” For more on this, see this great post by Jay Dicharry from the UVA Speed Lab.

What I find interesting about this study is that it shows yet again that individual responses are highly variable when it comes to running mechanics – it’s why generalizations are in fact so hard to make. People respond differently to different interventions, and thus Amby is right when he suggests that generalizations about the most appropriate shoe and/or foot strike should be avoided. Different things will work for different people, but that’s also why I disagree with Amby when he expresses his lack of faith in anecdotal reports and refers to them as “bad science.” One of the first things we teach in elementary biology classes is the scientific method, and one of the foundations of that method is observation. Anecdotes about people getting hurt or overcoming injury through running barefoot or in minimal shoes are observations, and they allow scientists to generate and test hypotheses, just as the authors of the studies referenced here have done.

It’s also worth pointing out that science also does have limitations, and one of those is that we are very good at describing majority patterns, but studies are often very bad at telling the individual what is best for them. Non-systematic results in biomechanics studies, as well as anecdotal reports from runners who experience different outcomes when experimenting on themselves, all seem to argue that we will never have one single answer that applies to all runners when it comes to form and shoes. That’s why I view the discussion around barefooting and minimalism to be so important – it is helping to increase variety in footwear options for a highly variable and oft-injured population of runners. The “bell curve” that Amby refers to in his post has long been skewed to one type of shoe, and what I hope is that through individual experiments an additional research we will gain a better idea of where the tip of that bell should be.

At the end of the day, scientific studies can be a useful guide, but when you are a chronically injured runner, sometimes waiting for an answer in a scientific paper can take too long. Sometimes taking a risk and trying something dramatically different can be of great benefit. Sometimes it might break your foot. Without anecdotal reports from individual experiments though, we wouldn’t have the basis upon which to generate and test hypotheses about why some people get one result and some get the other.

Good discussion Pete. It has been a controversial issue and with these new results it has become even more controversial.What I find interesting in this new research in the way it differs in its results from that of Lieberman et al. 2010 paper. According to Lieberman the impact transient was lacking in FFS during barefoot toe-heel-toe runners compared to RFS during shod and barefoot heel-toe running. However, according to this paper both groups have shown a distinct impact transient (similar VILR). Was the original study bogus or is this study somehow came up with the bad results? Or did one of them chose the sample that suited their hypothesis. It is hard to know right now. I am a barefoot fan myself and have transitioned to VFF and minimalistic shoes but until yesterday I was very confident when I mentioned the results of the Lieberman’s study to people who wanted to understand the benefits of barefoot running. Unfortunately, with these new results, I am not so sure anymore as to which study results I should rely on.

A few things – this is an abstract and not a peer reviewed manuscript, so

the details are not fleshed out as much as in the Lieberman paper. Second,

there is always a loading rate, even if the transient is absent. They just

measure the slope of the curve that corresponds to the time of the transient

if it were present. Third, to me the acclimation issue is a big one –

results might be different if someone is running barefoot for the first time

versus having done so for many months.

Thanks for clearing that up! It would be nice to see some research on runners who have transitioned from shod to barefoot running.

I agree – a long term acclimation study would be very cool.

I should also re-emphasize that Lieberman essentially showed the same thing

with regard to VILR. It was the impact peak that he found to be absent.

Hey Pete:

Here’s a link to another new study, this one done by a high schooler: link to runningtimes.com…

I’m not much of a scientist, so I won’t comment on the study. I am just glad to see such a young kid adding to the growing list of studies on running.

Enjoy,

Aaron

Here’s the abstract:

Rebecca Leong

First-Place: $50,000 ScholarshipColumbia River High SchoolVancouver, Washington

The Effect of Footwear Habits of Long-Distance Runners on Running-Related Injury: A Prospective Cohort

Abstract

Every

year, approximately 60 percent of long-distance runners will suffer a

running-related injury that not only temporarily affects their training,

but can also have long-term psychological and physical effects.

Following recent publications, barefoot running has gained attention for

its claim to reduce running-related injury and promote a natural

running stride. This study directly compares injury rates between

barefoot and shod runners, and for the first time quantitatively

evaluates the risk present in transitioning from shod to barefoot

running. The following question will be examined: How does footwear

habit (barefoot, transitioning or shod) affect the injury rates of

long-distance runners? A series of surveys were e-mailed to participants

to record running habits and injuries suffered over a course of 12

weeks. The data supported that runners transitioning from shod to

barefoot running had the highest prevalence, with an average of 32

percent of its runners in an injured state each week. Shod runners had

the lowest prevalence, with 21 percent and barefoot runners (prevalence

of 29 percent) were in the middle. Furthermore, relative risk

calculations, which are based on a ratio of prevalence, showed that

barefoot runners are 1.35 times as likely to suffer an injury as shod

runners. Transitioning runners are 1.48 times as likely as shod runners

to suffer an injury. This study supports that shod running presents the

lowest risk of injury for distance runners. Despite recent speculation,

barefoot running in industrialized countries does not appear to reduce

running-related injury. Thus it is not recommended that healthy runners

transition to barefoot running for the sole purpose of reducing injury

risk.

I saw that – very cool, and she is going to college just up the road from

me. It’s hard to really know the details from a short abstract, but I’d more

or less concur with her conclusion that there is no real compelling reason

for a healthy runner to go barefoot full time. Even still, 70% of the

barefoot runners seemed to do just fine, and it would be interesting to know

why they had started doing it and if it had helped them overcome a previous

injury. Gets back again to individual responses vs. group means.

I went from shod to minimalist about 2 years ago and the debate is pretty much over for me. I know, just an another anecdote but I can’t imagine, landing on my heel today even though I did it at 100km/week for 8 years prior. There are a few things that I noticed during the transition that have not come up.

When I was a heel striker, with big shoes (NB 1050) my quads would get sore much much quicker and the soreness could last for days (DOMS) depending on how hard I pushed. Now with a forefoot strike and minimal shoes (Merrell Barefoot Trail Glove) I can run for hours, hard! and not have sore quads at all. My Achilles are sometimes a little sore but nothing like the quad pain that I got when heel striking.

The other thing that I’m curious about is the affect that forefoot striking has on the calf muscles. Does a forefoot striker end up have larger calf muscles and if so, how does the extra weight affect performance?

Your experience is why I don’t think minimalism is a fad – most people I

know who have made the switch claim they will never go back, even many of

those who have been injured in the transition. Personally, I don’t see

myself ever running in a heavy shoe with a 12mm heel lift again, even if I

break my foot tomorrow. I just vastly prefer the feel of the ground

underfoot.

Your experience is why I don’t think minimalism is a fad – most people I

know who have made the switch claim they will never go back, even many of

those who have been injured in the transition. Personally, I don’t see

myself ever running in a heavy shoe with a 12mm heel lift again, even if I

break my foot tomorrow. I just vastly prefer the feel of the ground

underfoot.

I totally agree with you on this Pete. I injured myself in April while transitioning to a more “minimal/natural” running gait with a midfoot/forefoot strike (like most I’d been a heel-striker for most of my life). I was stupid and went from running 3-4 miles every 2-3 days to running 7 miles one day then 6 miles the next. My new running “style” just allowed me to enjoy it so much more than I ever had before, and I did too much too fast. I’ve since recovered and am sticking to a 10% plan to get me to the CIM in December. I’ll never go back! I love running free and light too much to ever buy the “gold standard” 12mm heel lift heavily-cushioned shoes again.

Also, good questions about quads and calves, and I don’t have an answer. I

don’t know that my calves have necessary gotten larger, but they feel more

toned. An MRI study should be able to answer this pretty easily.

Pete, I guess I would be classified in the more radical side of the spectrum. However, I am not one of the bitter barefoot hippies that make us bare footers look bad. I began my minimal movement about a year ago wearing old water shoes. My chronic injuries disappeared, and so I burned out the forefoot on those in a couple hundred miles. Since I did not have the money for anything else besides my old Nikes, I ran barefoot and absolutely loved the feel of the ground under my feet. I bought some ZEM “shoes”, and, although they are constructed a bit weird, log most of my miles on them. They provide good ground feel (i.e. stepping on small stones hurts) but do protect my now leather skinned feet. This crazy setup works great for me; I haven’t run in any cushioned shoes in about 6 months. I understand that this will not work from everyone. I’m very young, so my Achilles tendon was not too compressed, and I acclimated quickly. Other people need cushioning, and this is understood. However, I think that no one should need more shoe than a Kinvara provides. On the subject of the different muscles used to run correctly: As flammon said, quads are not really used. All my running is in my ligaments, calfs, and arches. If I stay under a pace where my breathing rate does not increase, then I can run indefinitely. The biggest plus: running the way we evolved is much more fun.

Apparently I still need to work on my form… link to facebook.com…

Sorry to see that. Is that the base of your 5th metatarsal?

Another great post Pete. I’m a little confused about this study, and many other studies out there. I’ll preface my comment with an obvious observation: I am not a scientist. Having said that, it seems any study can be changed/designed to obtain the desired results. In other words, it appears that these PhD’s can “load the deck” as it were in order to “prove” whatever fact they want to.

I would guess that the designers of the study headed by James Becker are no fans of the barefoot “movement” and they set out to “prove” that unshod running is no better than shod. I came to this conclusion due to the fact that they had habitually shod runners perform the unshod running (as you pointed out).

Now I am not a barefoot runner, but I do realize that there is a definite adjustment period when switching from shod to unshod. Speaking from experience, when I switched from a heel-striking gait to a midfoot/forefoot strike I had a rather long adjustment period. I can imagine that the adjustment from shod to barefoot is longer. If you ever see someone who has been running barefoot for a while you’ll realize there is a definite technique involved that, when done “correctly”, looks like art in motion.

Anyhoo, it seems there aren’t any unbiased studies out there to honestly examine the effect of shod vs. unshod running. Again, I am no science guy, but in order to have a good study don’t you need a rather large group of individuals to test (definitely more than 11)? Wouldn’t they need 3 groups (habitually shod, habitually unshod, and a control group) of runners to test to get to the bottom of this question?

I am honestly curious about this. Do scientists have to meet certain criteria in order to be able to present their “findings” to other scientists and the public? If they do, do you think the criteria is stringent enough?

Pete, if you’ve already talked about this in a previous post I’m sorry to have not done my homework. There are just so many “studies” out there that claim to prove/disprove the benefits of a more “natural” running style. It can get a little frustrating.

For the individual n=1, it is all about experimenting to determine what is best for you and your body. For me, its all about minimal shoes and a midfoot/forefoot striking pattern. It has made ALL the difference. I have never enjoyed running as much as I do now. (Sorry for the LONG post Pete)

Jeff,

The lack of acclimation is a big problem for many studies that have compared barefoot and shod runners. Only two that I am aware of have studied habitual barefoot runners (Lieberman and Squadrone), and I’m not aware of any study that has looked at changes associated with long term acclimation to barefoot running. The latter really needs to be done.

Regarding sample sizes, limitations are due to finding suitable subjects (human research is tough), and the time required to collect and analyze mountains of data. Samll sample sizes are pretty typical, and that’s also important to keep in mind. Peer review will usually take care of any major errors in a paper, but sometimes things slip through. All of this being said, I don’t see anything particularly wrong with this study – humans are highly variable, and I suspect even moreso when they are running barefoot for the first time. I’m just not sure that it tells us much more than what will happen on your first barefoot run. Doesn’t say anything about how things might improve with time.

Pete

Some good questions Jeff, and ones i am sure many people ponder over. I guess the fact is that like good drivers and bad drivers, there are good scientists and bad scientists. the essence of research is to ask a question.. is the earth flat.. develop an hypothesis.. ‘ we propose the earth is flat because..’ and then, with all means currently at hand, to test that hypothesis and come up with an answer to the original questiuon.

Now, bad scientists can manipulate this process in a number of ways, either by manipulating the design of the experiment to bias the result, or by employing outright fraud. An excellent example of this is the research f Dr. Andrew Wakefield who fraudulently manufactured results to an experiment connecting the MMR (measles mumps and rubella) vaccine to autism. As a result of a paper he published in Lancet some 10 years ago, the rate of immunisation for these diseases in babies plunged from about 90% to vitually nil.He cause a panic that spread from the UK to the USA and canada.. even Oprah got on the bandwagon! As a result of this, parents were left to pick up the pieces of babies who were blinded, became deaf or died.An absolute tragedy and a dismantling of one of the greatest triumphs of modern medicine. Years later, Andrew Wakefield was proven to have commited fraud, to have manufactured the link between MMr vaccine and autism (after an exhaustive investigation by the British Medical Association into any possibility of a link) and was subsequently struck of the medical register in March of 2010. Bad science.. bad doctor, devistating result for many.

Fortunately in the world of shod and barefoot, we are not playing for such high stakes, but quality of science is still very important.

End of the day, anyone working with a credible university has to submit their proposed study to the University ethics board. The study cannot proceed without ethics approval, and, as you can imagine, this independent audit is incredibly important when we are talking about experiments on real people.

if ethics are approved, and the panel looks at the quality of the proposed science as well as the ethical issues, then the study can proceed. Once completed, every researcher has a goal to have his or hers research published. We then look for the best possible journal to showcase our months or years of hard work. Every scientific journal in the world has what is called an impact factor, which is a score form 1-5. the bigger the number, the more pretigeous the journal and the more diofficult it is to get your work published. Any journal with an impact factor greater than 2 is pretty tough to get published in.

Once one has decided where to aim the finished paper, it is then submitted to the desired journal. the poaper is then scrutinised by at least 2 anonymous reviewers who would be considered experts in the field of the submitted paper. these reviewers will then examine every aspect of the paper, critique it, ask for changes if appropriate, and then, with complete impartiality, accept or reject the paer for publication.

It is extremely hard to manipulate this process with a quality journal. So.. what you read is normally the best knowledge for that particular moment in time.. and .. this can change very quickly.

The problem with the abstracts pete has pointed you to, is that these are not subjected to the same scrutiny, because they have not gone through the journal process. that is nlot to say thay may not be excellent science!

In relation to the sample size.. it depends totally on the project. For example, a study working with cadavers would normally be great with 5-10. most studies start off by dong a power analysis to determine how many subjects are required to give the study “statistical power”. this can vary form half a dozen to hundreds. Obviously though, the more you can gather the greater the power.

bottom line is.. most researchers have a genuine thirst for an answer, even if it does not fit a proviously held view. My experience has always been that the answer to the question is IT.. always exciting.

hope this helps

regards

Simon Bartold

Pete.. on a personal note been trying to contact you personally by email .. cant seem to get through.. any tips?