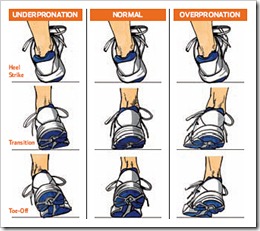

Image from the Runner’s World Wiki

Just before Christmas I received a very thoughtful and well researched email from ultrarunner Phil Shaw. In addition to being a very successful long distance runner, Phil is also pursuing a doctoral degree in podiatric medicine – quite a dangerous combination!

Like me, Phil feels that the current paradigm of attempting to control foot motion through fancy shoe technology of questionable effectiveness has gone too far (for more on my thoughts about this, check out my post on the “pronation control paradigm”). He wanted to share with me some thoughts he had put together on the topic as a result of an extensive review of the scientific literature on barefoot running and forefoot striking and how they can both help reduce pronation without any need for external technological intervention. Phil’s work largely speaks for itself, and I’d like to thank him for allowing me to share it here on Runblogger. Enjoy!

Forefoot Striking and Pronation: What Science Tells Us

It doesn’t take much time on the internet to realize that when it comes to minimalist and barefoot running, scientific evidence is spotty at best. Instead, one finds an abundance of anecdotes and an occasional citation. In an effort to parse the strong evidence from the weak, a few fellow doctoral students and I recently wrote a literature review of barefoot running biomechanics. Our goal was to formulate a complete and evidence-based biomechanical model of barefoot gait and describe its potential implications for overuse injuries. Ultimately, we reviewed 39 papers that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The publications covered many subjects relevant to barefoot running, and our review is beyond the scope of this blog (like most scientific papers, too dense as well!) but one pattern in particular may be of interest to minimalist runners. I’d like to share it with readers of Runblogger.

First, let me introduce myself. I’m 25 and I’ve been running ultramarathons for 9 years. I’ve raced 12 mountain 100 milers, won a couple of them, and run a 2:39 marathon. I usually run around 90 miles per week. I’m currently in podiatric medical school seeking my doctorate in podiatric medicine (DPM). I’ve been running exclusively in minimalist shoes (Brooks Mach 11 mostly) since Summer 2010, and generally I’ve benefitted from the change. Obviously, there is some personal motivation in my interest in running biomechanics.

One of the most frequent claims of barefoot and minimalist running advocates is that a forefoot strike reduces impact forces. I’d like to examine how those impact forces are attenuated in a forefoot vs. heel strike, and what it might mean for overuse injuries. Instead of focusing on impact force magnitude, which may or may not be implicated in overuse injuries, let’s look instead at pronation. Excessive pronation is associated with multiple overuse injuries including those awful nemeses plantar fasciitis, medial tibial stress syndrome (aka shin splints) and patellofemoral syndrome (aka runner’s knee). From our review of barefoot running, we found a pattern suggesting that a forefoot strike may reduce pronation compared to a heelstrike.

Six studies explicitly compared rearfoot motion in subjects running barefoot and shod. Of those six studies, three found a significant reduction in rearfoot pronation in barefoot runners,1,8,11 two studies found no difference between the conditions,4,12, and only one study found greater pronation when subjects ran barefoot.9 This is hardly an strong trend, but when we looked more closely, we found that all but two of the studies required participants to be heel-strikers (Runblogger’s note – unfortunately, this requirement is quite common in the scientific literature on running mechanics). Of those two studies that allowed forefoot striking, both found a significant reduction in rearfoot pronation when barefoot.1,11 Additionally, Morley et al. 2010 found a reduction in pronation when heel-strikers ran barefoot. Interestingly, individuals with the greatest pronation saw the most reduction in rearfoot eversion. Of the two studies that found no difference between conditions and the single study finding more rearfoot eversion in barefoot runners, all required participants to heel strike. Additionally, all studies agreed that rearfoot eversion velocity was slower in barefoot runners, suggesting that the pronatory motion is more controlled when barefoot.

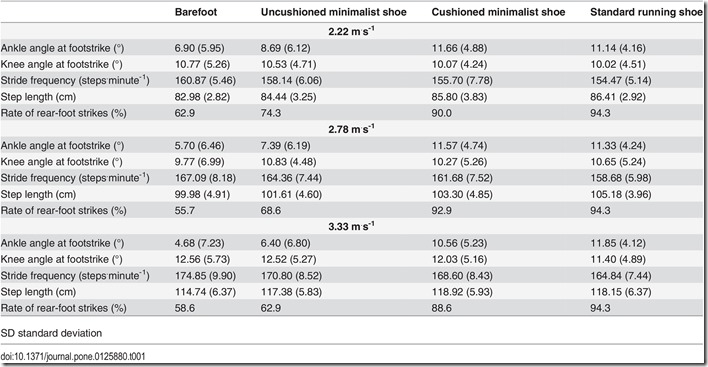

What do these results imply? Not much, until we look at one more finding. Of seven studies that investigated sagittal plane motion at the ankle (I.e. dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, or pointing the front of the foot up and down in side view), all agreed that barefoot runners strike the ground with a significantly more plantarflexed foot (front of foot angled more downward).1-3,5-7,10 Even in studies that required subjects to be heel strikers, subjects struck the ground significantly more plantarflexed. Furthermore, the longer the accommodation period to barefoot running, the more the runners plantarflexed at contact. In other words, with more time running barefoot, runners are more likely to land with a midfoot or forefoot strike. This is most evident when subjects are “habitually barefoot runners,” meaning they’ve run barefoot or in minimal shoes for at least six months, but the trend is evident after just 4 minutes on a treadmill in runners who never train barefoot. Avoiding a heel strike is clearly an adaptation mechanism when the foot has minimal cushioning available.

We know that barefoot/minimal running is associated with a significantly more plantarflexed foot at contact. We also see data suggesting reduced pronation when runners shift toward a forefoot strike. We concluded that a forefoot strike may therefore reduce rearfoot pronation. Why might this be?

In a forefoot strike, impact forces are attenuated through a combination of rotational motion at the ankle joint and energy storage in the elastic Achilles tendon. Some pronation occurs, slowed primarily by the tibialis posterior muscle (the primary inverter of the foot and supporter of the arch). In a rearfoot strike, the ability to dissipate energy through ankle joint rotation and store potential energy in the Achilles tendon is dramatically reduced. Motion that would occur at the ankle joint occurs elsewhere: the subtalar joint (the joint in the rearfoot between the talus and the calcaneus that allows one to invert and evert the foot). Instead of sagittal plane motion at the ankle, the subtalar joint pronates excessively in the frontal plane, and it pronates very rapidly. In other words, heel striking may cause excessive pronation because impact forces cannot be transmitted through a mobile ankle to the gastroc-soleus complex (calves). Rather, the body dissipates impact forces at a different joint in a different plane of motion.

We reviewed many other facets of barefoot running, such as knee joint motion, shear forces, plantar pressures, and more. The idea that a forefoot strike in a minimally cushioned shoe without pronation control could actually reduce excessive pronation, however, was particularly interesting to me. I hope readers of this blog will think the same.

Phil Shaw

References

1. De Wit B, De Clercq D, Aerts P. Biomechanical analysis of the stance phase during barefoot and shod running. J Biomech. 2000 Mar;33(3):269-78.

2. Divert C, Baur H, Mornieux G, Mayer F, Belli A. Stiffness adaptations in shod running. J Appl Biomech. 2005 Nov; 21(4):311-21.

3. Divert C, Mornieaux G, Freychat P, Baly L, Mayer F, Belli, Belli A. Barefoot-shod running differences: shoe or mass effect? Int J Sports Med 2008; 29: 512-518.

4. Eslami M, Begon M, Farahpour N, Allard P. Forefoot-rearfoot coupling patterns and tibial internal rotation during stance phase of barefoot versus shod running. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2007 Jan;22(1):74-80.

5. Kurz MJ, Stergiou N. The spanning set indicates that variability during the stance period of running is affected by footwear. Gait Posture. 2003 Apr;17(2):132-5.

6. Lieberman DE, Venkadesan M, Werbel WA, Daoud AI, D’Andrea S, Davis IS, Mang’eni RO, Pitsiladis Y. Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature 2010 Jan 28;463(7280):531-5.

7. McNair PJ, Marshall RN. Kinematic and kinetic parameters associated with running in different shoes.Br J Sports Med. 1994 Dec;28(4):256-60.

8. Morley JB, Decker LM, Dierks T, Blanke D, French JA, Stergiou N. Effects of varying amounts of pronation on the mediolateral ground reaction forces during barefoot versus shod running. J Appl Biomech. 2010 May;26(2):205-14.

9. Pohl MB, Messenger N, Buckley JG. Forefoot, rearfoot and shank coupling: effect of variations in speed and mode of gait. Gait Posture. 2007 Feb;25(2):295-302.

10. Squadrone R, Gallozzi C. Biomechanical and physiological comparison of barefoot and two shod conditions in experienced barefoot runners. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2009 Mar; 49(1):6-13.

11. Stacoff A, Kälin X, Stüssi E. The effects of shoes on the torsion and rearfoot motion in running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991 Apr;23(4):482-90

12. Stacoff A, Nigg BM, Reinschmidt C, van den Bogert AJ, Lundberg A. Tibiocalcaneal kinematics of barefoot versus shod running. J Biomech. 2000 Nov;33(11):1387-95

Good article. I’ve got feet like pancakes thus tend to “overpronate”. I’ve always thought the only way I could run was with tank-like shoes and heavy orthotics, and honestly thought only people with perfect feet could, or should go barefoot or minimal.

Last fall I started making the move toward the minimal end, to where I’m in NB101s with very light insoles, and consider myself a pretty good mid-foot runner. I’m faster, my shin-splints and ITB have gone away, and I honestly have more fun running. But I’ve been hesitant to go any further. So I’m glad to see someone take a scientific approach to this, and show that perhaps my issues weren’t just something I was born with and would have to deal with, but something I could take control of.

Is reducing pronation always a good thing though? Pete had posted a video of Haile Gebrselassie running a marathon (I believe it was his 2:03:59) and he was pronating a lot. The commentary said something along the lines of “the pronation is protecting his body from the impact forces of running ~4:40 pace on pavement.”

Thanks for the analysis Phil!

The point Phil is making is that in a forefoot strike, impact absorption is

taken on by the calf and achilles. My personal feeling is that pronation can

be a problem, but that it’s not always the evil thing that it’s made out to

be. And I certainly don’t think that our entire basis for assigning running

shoes should be the amount of pronation exhibited by a runner. Overpronation

could very well be a symptom of heel striking caused by overcushioned shoes,

so pronation control shoes may just be a solution engineered to deal with a

problem caused by the shoes in the first place. We are fighting technology

with even more technology, when doing what is most natural may avoid the

problem altogether. I should also note that Geb was wearing a shoe that

another guest poster seemed to indicated vastly increases his degree of

overpronation (Adidas Adios I think).

Pete

Interesting article. I too had a pronation problem but have switched to minimalist shoes and ditched my orthotics (wore them for 15 years). I am on day 60 of this experiment and have had no issues thus far. This article is very interesting in its discussion of the forefoot strike and pronation. I have developed more of a forefoot strike wearing the minimalist shoes.

What is “excessive pronation”? I guess the idea is that a heel-striker will pronate more than a forefoot striker, which makes logical sense. If one is pronating too much, i.e., overpronation, altering the stride to a manner that has less pronation will, by definition, reduce pronation and thus may take the “over” (or “excessive”) out of the equation. Trying to do it with a shoe may not work, and that may explain why people who have injury issues may improve (injury-wise although not necessarily speedwise) by going midfoot or forefoot.

Separately, or not, here’s something from Amby Burfoot on Benno Nigg.

Joe,

That’s the question – how much is too much when it comes to pronation. I

read the Nigg article on Amby’s blog. I actually have Nigg’s new book that

Amby refers to – cost an arm and a leg but it is interesting. My conclusion

is that there is simply just so much that we don’t know right now, and we

are all trying to figure this stuff out. Nigg thinks impact is unimportant,

whereas others think it’s very important, at least loading rate (people like

Irene Davis and Daniel Lieberman). It becomes a case of pick your favorite

expert. The science is evolving quickly right now – it’s a very exciting

time.

Pete

A few things:

1) Pronation has not been shown to be directly related to injury anyways–see Benno Nigg’s article here:

link to ncbi.nlm.nih.gov…

2) Any study comparing barefoot to shod foot motion (including rearfoot eversion or “maximum pronation”) is highly suspect unless it used bone pins to measure actual bone movement–when using markers on a shoe, the actual bones only move about half as much as the shoe does, so when you run barefoot, you will appear to pronate less, even if your mechanics did not change at all. I have a paper on bone pin measurements somewhere, I’ll see if I can find it later.

It’s important to note that Nigg is contradicting quite a few other studies (I have 11 sitting in front of me) with the paper cited here when he writes that pronation is not shown to be directly related to overuse injuries. Pronation, of course, is a natural, necessary motion. Too little pronation is associated with a certain set of pathologies, and too much is associated with a different set. When we say that pronation per se is not associated with injuries that may be true. Pronation beyond a normal range is associated with overuse injuries.

The second point is a great one. Unfortunately, intracortical bone pins are not allowed for biomechanical research in the United States, at least to my knowledge. The one paper I reviewed that utilized bone pins (Stacoff et al. 2000) was done in Denmark (bone pin studies seem mostly to come out of Scandinavia). Stacoff et al. 2000 (Nigg was the second listed author) found no difference in pronation, but used only heel-toe gait. Other researchers have tried to avoid the pitfall of measuring shoe motion (rather than bone motion) by using sandals and placing their markers directly on skin. This is also an inherent source of error, but better than shoe measurement.

Thanks for the input.

Phil Shaw

I was just watching the video in this older post link to runblogger.com… and how they explained why the impact force for a forefoot stirke is not as immediate as with a heel strike because the foot allows some of the vertical impact to be transformed into rotation as the heel lowers.

If i understand correctly what Phil Shaw is saying above is that with a heel strike we still see some of that force being converted into rotation,but as pronation, further more because of the foot structure and inability of the tibialis posterior muscle to counter act it it is faster and more ponounced that with a fore foot strike.

Another point that occured to me is regarding the construction of minimalist shoes, more specifically those with reduced drops. id postulate that the reduction in offset provides more range of movement in which the foot can disperse the impact, thus allowing greater time to control the speed of pronation.

given that its possible to forefoot strike in a shoe with a higher heel, i wonder then if the rate and amount of pronation for those actually performing a forefoot strike isnt reduced as the heel/toe offset of their shoe is reduced?

This is a very interesting thought. I’ve long suspected that forefoot

striking in a shoe with a large heel lift makes no sense, and this could be

a plausible reason as to why it could actually be counterproductive. I find

that a small heel lift (about 4-6mm) can help reduce calf soreness from

midfoot/forefoot striking because it presumably reduces the amount of

stretch of the calf and achilles. I’d really like to see a study comparing

forefoot striking in shoes of varying heel height. Maybe I can mess around

with my camera sometime.

Pete

Another interesting post and interesting debate. As a recreational runner and as a musculoskeletal radiologist I have a strong particular interest in this topic. I too have struggled with nagging injuries while running, the worst of which is a recurrent posterior tibial tendonitis. Most of my life I have been told, and have noticed myself that I am an “overpronator”, however I have never heard anyone define what delineates “normal” pronation from overpronation. I have experimented myself going from a heel toe strike in the rigid motion control shoes to a now primarily midfoot, forefoot strike in minimalist shoes (Saucony Kinvary, Adidas Adizero). My posterior tibial tendinitis is improving (hasn’t disappeared) but has been replaced with an achilles tendonopathy (which I believe is my fault since broke the rules and increased both my speed and distance dramatically and rapidly). Any scientific design to research this topic will need to involve a large number of runners from all walks of life, all shapes and sizes, and likely utilize high speed imaging. Bone pins would not pass any IRB review in the USA. They do some strange things in Scandinavia, but do get some great science from it (don’t know if that’s good for the folks in the studies though!) Maybe flouroscopy evaluation if we can design a machine to image the bones and then slow down the process, and find some volunteers willing to irradiate their feet while running.

Love the discussion.

I also wonder whether bone pins and/or the anesthesia involved might

influence gait parameters? You’re right though – would be nearly impossible

to do a study like this in the US, nor would it be easy to find volunteers.

Could not imagine my IRB allowing it.

Using fluoroscopy has been done in animals for locomotion studies, wonder if

it would be safe enough to do on humans?

Stefanyshyn (2003) did a study where they basically found that very few

people are actual overpronators, even if they have been told they are or

consider themselves to be overpronators:

link to staffs.ac.uk…

Pete

great post! i’m really looking forward to more research in this area. Hopefully someone will start doing some studies on “flat feet” and barefoot/minimalist running. doesn’t any one know if the test subjects where people with “normal” feet?

Hi Pete,

Thanks for posting this. You wouldn’t have access to Phil’s literature review, would you?

Thanks!

No, they are working on a journal publication, so I understand their

need to not share it all at this point.

Pete

On Thursday, January 13, 2011, Disqus

Understandable, thanks for the response!

Edit: I was under the impression that the triceps surae contribute the largest supination moment around the sub-talar joint – the tibialis posterior is mechanically better placed but is much weaker than the triceps surae. It is the loading of the triceps surae and Achilles tendon during forefoot strike that both absorbs the impact energy and controls pronation of the subtalar joint.

The nice implication here is that the increased activity of the triceps surae in a forefoot strike compared to a heelstrike may also contribute to pronation control.

Phil Shaw

deleted

I just returned from Jay DiCharry’s SPEED lab in Charlottesville, NC. His lab is only one of two in the world where average joe’s can get a 3D analysis of their running to get faster or solve injury problems. link to uvaendurosport.com…

He was also a featured speaker at the Newton Running Conference last August in Boulder and is one of the most respected run biomechanics guys out there.

I had 5 hours to pop off as many questions as I could and one thing I took away from him is that over-pronation really isn’t that big of a deal. I believe he uses a measurement of “Navicular Drop” to determine if a runner needs stability shoes or not. And it’s not that many people out there that do.

It’s really hard to correct over-pronation if the runner is running efficiently since max pronation occurs at toe off, far later in the gait cycle than most orthotics or shoes can correct it.

Glad to see the new generation of podiatrists if coming out with an interest in this stuff. All of the guys in our town are totally old school…they use very outdated methods and orthotics.

Interesting stuff!

Unfortunately, many shortcuts are used when looking at pronation. A full analysis may also include medial malleolar position, bulge of the talar head, resting calcaneal stance position, navicular drop, and other factors. All these can be summed to provide a “pronation score” that is a much more accurate description of a foot’s position than something like “high arch” or “low arch,” which have not proven to be very useful when prescribing athletic shoes (for example, see Ryan et al. 2010 The effect of three different levels of footwear stability on pain outcomes in women runners: a randomised control trial. Br. J. Sports Med.)

Eric, do you have a source for your comment that maximum pronation occurs at toe-off? Certainly in walking, the sub-talar joint supinates at heel-off, and I would assume that a similar process occurs during running, where maximum pronation would occur close to mid-stance (at maximum load and before the triceps surae are most active). A quick search find lots of data for sub-talar rotation during walking , but I can’t find much for running.

Phil,

It is very exciting to hear about the new research you are contemplating. I hope you will be able to achieve a couple things that others in your field have not: 1) have a large enough number of test subjects to convincingly eliminate chance (those studies you cited looked at so few people, they don’t even approach statistical certainty), 2) control for foot type and joint flexibility in the foot (such as first ray hypermobility, hallux limitus, equinus). When we are trying to understand the implications of relatively small motions and moments in an extremely complex system, we have to do as much as possible to remove confounding variables.

Thanks for bringing up these points. I couldn’t agree more. For any solid conclusion, we need to see studies with much better controls, many more subjects, and a longer time frame. Will that happen soon? I doubt it. So far, we can look at studies of very limited scope. I get the sense that many runners want to answer the questions, “which is better, forefoot or rearfoot striking” or “which is better, barefoot or shod running?” Injury rates would be a nice way to quantify this judgement, but will be so fraught with potential error that I would hesitate to make any conclusion. Did the study control for mileage? Intensity? Terrain? Running experience? Rest and recovery time? Any number of other factors? For now I’ll have to be content to look at how gait is affected by parameters we can more easily measure.

Anyway, it’s fascinating stuff. Thanks for reading.

Phil Shaw

This is why so much of this comes down to personal experimentation. Science

can provide information on general trends, but generally can’t “prescribe”

what is best for the individual. I’m continually amazed at how many studies

report that results were non-systematic. If what you are doing isn’t

working, try something different. Until recently though, with the advent of

an increased recognition that there are options when it comes to form and

footwear, trying something different was very hard to do.

Pete

Hi I just found your blog and think your info is fantastic! I am in Bedford and am searching for a running group/club in my area. Do you know of any? thanks,

Judy ranrnrunning.com

ran

ranrunrunning.com

Could you provide the citation for Shaw’s literature review? I’m very interested in reading it!

Don’t think he ever sent it to me – if he left a comment you might be able to ask him directly – can’t remember if he did, and I answer these comments via email.