The running science blogosphere has been popping over the past few weeks with articles touching on various aspects of the role of stride rate in running, particularly how it relates to both running speed and injury prevention. Here’s a quick summary of some of the relevant posts:

The running science blogosphere has been popping over the past few weeks with articles touching on various aspects of the role of stride rate in running, particularly how it relates to both running speed and injury prevention. Here’s a quick summary of some of the relevant posts:

1. Back on February 5, I wrote a post on gait retraining in which I described physical therapist Blaise Dubois’ approach to treating broken runners in part by getting them to up their cadence to between 170-190 strides per minute. He has had good clinical experience using this approach, and the scientific literature base on the benefits of gait retraining for the treatment of running injuries is growing.

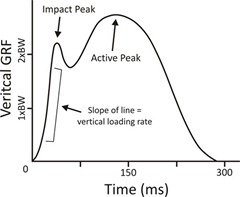

2. Jay Dicharry from the UVA Speed Lab weighed in and suggested that adopting a running form that incorporates a foot contact closer to the center of mass can be an effective way to reduce vertical loading rate (the speed at which force is applied to the foot upon ground contact), even if footstrike is still on the heel. Increased loading rate has been linked to some types of running injuries, thus reducing it could be useful from an injury prevention standpoint. In his post, Jay also points out that “barefoot running, minimalist running, and increasing cadence (faster cadence means you don’t have time for your foot to reach out far in front of the body) are all effective tools to accomplish the end goal of decreasing loading rate.”

3. On his Runner’s World Peak Performance Blog, Amby Burfoot praised the simplicity of the stride adjustment approach, and discussed the ubiquitous 180 stride/min number that we see commonly thrown around as a target cadence these days. He joked that he “wouldn’t be surprised if runners soon know their stride rate as well as they know their height, weight, cholesterol and blood pressure.” He also measured cadence from a few elites on YouTube, and suggested we be wary of trying to match the cadence of Olympians (good advice!).

4. Next, Steve Magness over at the Science of Running contributed his thoughts, emphasizing in particular that a 180 cadence is not a magic number that all runners should strive for. He views stride rate as a more individualized variable – each person may be a bit different in their “ideal” stride rate. Steve also focuses on the relationship between stride rate, stride length, and speed, pointing out that runners can and do manipulate either rate or length to increase their running speed (here’s a great, older post by Steve on this topic). He concludes by pointing out that stride rate is an outcome of your biomechanics, and that it should change as a result of your form, and that striving solely to adjust rate directly may not be the right approach. He worries that we focus too much on stride rate because it’s easy to measure.

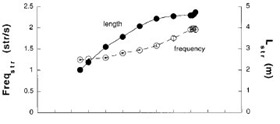

5. Finally, Alex Hutchinson at Sweat Science wrote two posts on the stride rate-stride length topic (here and here), and he also points to data that speed increases can come about by manipulating either stride rate or stride length. I sent Alex a paper (Weyand et al., 2000) I had just read on the topic, and he posted a graph (see above right) from that paper showing that initial increases in speed seem to occur more-so by manipulating stride length, whereas achieving top speed seems to involve increases in stride rate once stride length levels out. Alex also posted an informative interview with Max Donelan of Simon Fraser University, who stated that stride rate is often correlated with an increase in stride length based on his observations while conducting research to develop a device that uses sound cues to manipulate running stride rate. This seems somewhat counterintuitive given that the goal of increasing cadence is typically stated as being to shorten stride – I’ll explain why this isn’t exactly a correct way to think about this in more detail below.

5. Finally, Alex Hutchinson at Sweat Science wrote two posts on the stride rate-stride length topic (here and here), and he also points to data that speed increases can come about by manipulating either stride rate or stride length. I sent Alex a paper (Weyand et al., 2000) I had just read on the topic, and he posted a graph (see above right) from that paper showing that initial increases in speed seem to occur more-so by manipulating stride length, whereas achieving top speed seems to involve increases in stride rate once stride length levels out. Alex also posted an informative interview with Max Donelan of Simon Fraser University, who stated that stride rate is often correlated with an increase in stride length based on his observations while conducting research to develop a device that uses sound cues to manipulate running stride rate. This seems somewhat counterintuitive given that the goal of increasing cadence is typically stated as being to shorten stride – I’ll explain why this isn’t exactly a correct way to think about this in more detail below.

In an attempt to summarize all of this great discussion, I’d like to add some of my own additional comments and observations. Here goes:

1. Recent discussions of cadence/stride rate and the “magic” 180 number have mainly focused on the role of increasing cadence as a means to reduce injury risk. Why is this important? Steve Magness really hit the nail on the head in his post:

“Why is everyone in a rage over increasing stride rate? Because as I’ve pointed out before, most recreational runners simply overstride, which artificially creates a very low stride rate. Why? Because the foot lands so far out in front of the Center of Mass that it takes a while for your body to be over it and ready to push off. So, when some running form coach says to increase stride rate to X, what ends up happening is the runner is trying so hard to increase stride rate, he chops his stride a bunch by putting his foot down earlier and landing closer to his center of mass, thus decreasing the overstriding. Nothing particularly wrong with that.

Where we go wrong is in the logic that the stride rate increase is the key. No, it’s not. It’s the elimination of the overstriding. Using the cue to increase stride rate is a way for coaches/runners to reduce the heel striking overstride.”

The point that Steve is trying to make is that overstriding is the evil we are trying to correct by manipulating cadence. In other words, increasing cadence is not the goal in and of itself, rather, it is a means to achieve the goal of eliminating the overstride. What is overstriding? Defined simply, it is running in such a way that you reach forward with the lower leg and land heavily on the heel (usually) with an extended knee. The four images below all show overstriding in runners recorded at the 10K mark of the 2009 Manchester City Marathon – all four depict the exact moment of first contact between the foot and the ground.

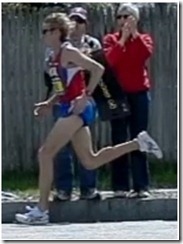

What we ultimately want is to avoid reaching out with the lower leg, and by doing so thus prevent landing on the heel with an extended knee. Ryan Hall from the 17.5 mile mark of the 2010 Boston Marathon provides a good example of a non-overstriding gait with a midfoot landing, a bent knee at contact, and a more-or-less vertical lower leg:

Current thinking is that increasing cadence helps to reduce overstriding because it forces you to put the foot down faster and closer to the center of gravity. Amby also discusses this in his post, saying “Dicharry believes load-rate is important, but not necessarily footstrike. He simply wants runners to be wary of overstriding, i.e., running with a low stride rate that results in placing the foot ahead of the center of mass.” In other words, reaching with the leg is bad, and increasing cadence can help us avoid doing that. Let me repeat – overstriding is what we are trying to prevent by manipulating cadence. If you don’t overstride, manipulating cadence might not be wise or necessary.

Regarding the observation mentioned above from Max Donelan that increased stride rate is usually correlated with increased stride length, my guess is that increased length might be due to greater hip extension on the back side rather than by reaching out front when we up cadence. I may need to get my camera fired up in order to experiment with this hypothesis – more reason for my neighbors to think I’m nuts!

2. Regarding speed, it seems pretty clear that stride length and stride rate interact to increase running speed. Which of the two is relied on as the primary mechanism may vary somewhat from person to person, and with different speed ranges.

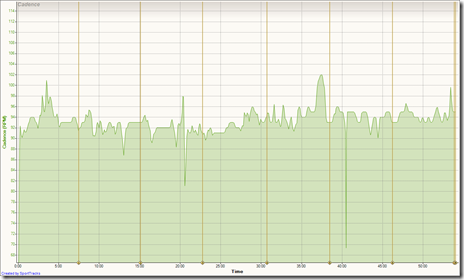

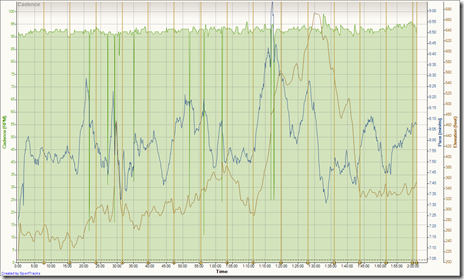

As so often happens with me, when I start mulling something like this, I feel the need to experiment on myself. I have a Wahoo Footpod that syncs with my Garmin Forerunner 305 and outputs stride rate in real-time, so I’ve been monitoring my cadence on my runs of late to see what I do out on the road. I’ve noticed that my cadence fluctuates right around 186 strides/min over a fairly wide range of speeds, from about 7:00/mile up to about 9:00/mile. However, when I push faster than a 7:00 pace, my stride rate ticks up, and I’ve seen it go as high as 200 when I really start to push the pace. What this tells me is that for most of my easy pace running, I regulate speed by changing stride length, but when I want to go fast, I increase my turnover and jack up the cadence. I was never aware of this until I actually measured it. For visual proof, below is a graph from a recent run showing cadence over the course of a 7 mile run – can you spot the two times I pushed the pace below 7:00 min/mile?

Here’s another graph showing my cadence (green) along with pace (blue) and elevation (brown) from a 15 mile training run (avg. pace = 7:58 min/mile) I did yesterday (click on the image to view a larger, clearer version):

What you’ll notice in the above graph is that my cadence stayed remarkably steady throughout the entire run, even though speed and elevation fluctuated a bit – average cadence was right around 186 strides/min. There was a slight uptick on the big downhill between miles 11-12, and also at the end of the run, which can be attributed to the fact that I was running on ice and had shortened my stride a bit to avoid slipping.

Based on this it seems that at least for me, initial speed changes are accomplished by varying stride length, whereas really picking up the pace requires an increase in cadence. I’m wondering if I reach a point where I can’t increase stride length much further, and any speed increase beyond that can only be accomplished by increasing cadence? Interesting to idea to ponder…

I also don’t know if my cadence has changed at all since moving into more minimalist shoes and working on my form over the past 9 months – I never measured my cadence prior to sometime last summer, and even then it was just by counting steps once or twice on a few runs. It seems right now that my body has found a comfort zone, and I look forward to experimenting a bit more with different speeds and shoes to see if things change.

3. How do shoes tie in with all of this? My view regarding minimalist shoes is that they can help you accomplish better form because the reduced heel helps prevent you from overstriding (particularly if you run at least periodically in something very minimal like the Vibram Fivefingers or Merrell Trail Glove). You can probably reduce overstriding in any shoe given enough effort, but it will be harder in a shoe with a typical 2 to 1 heel to forefoot thickness ratio (i.e., 12+ mm drop shoes), and part of me wonders if running with barefoot-style mechanics in a heavily lifted shoe might cause some problems – we just don’t know at this point.

I do know that a heel lift as small as 4-5mm is enough to pretty much negate any calf soreness I might get from running hard in a barefoot-style shoe like a Vibram, and for me this seems to be the sweet spot when it comes to speedwork, long distance training, or a marathon. I do a lot of training in zero drop shoes as well, and my opinion is that you can’t beat barefoot or something like the Vibrams/Merrells when it comes to working on getting a feel for your stride. When working on my stride last summer, I never paid attention to my cadence. Rather, I used Vibram runs and the cue provided by Steve Magness to “put my foot down behind me” – these worked well for me, and it is clear that there is more than one way to accomplish arriving at a form with a landing closer to the center of mass.

4. Finally, if you do feel that you are an overstrider and choose to manipulate cadence, I am a bit wary that the 180 number might get over-applied. Personally, I like the idea of finding your current cadence and upping it by 5-10%. There is evidence in the scientific literature to suggest that this can be of benefit, and it forces you to progress from your own baseline rather than striving to achieve a number that might not be appropriate for you.

5. Lastly, and it bears mentioning once again, any change you make should be gradual, and should be done with good reason. If your stride ain’t broke, don’t try to fix it. You may wind up doing more harm than good.

This post is part of the Minimalist Running Blog Carnival – many thanks to Jason Fitzgerald at Strength Running for organizing. To view other posts in the round-up, visit http://www.strengthrunning.com/2011/02/minimalist-blog-carnival/

very good article about running tech.

This is excellent. It consolidates everything I have been reading recently. Something I have noted recently is that, even if I try really hard to run in the same way regardless of the shoe, if I run in my minimalist shoe my legs hurt at different parts than when I run with traditional cushioned shoe. With mininalist shoe, I feel my achiles, and with my Nike Vomero I feel the beginning of my fascitis. I have eliminated all the other aspects and reached the conclusion that it is really the shoe. Interesting, isn’t? I remember you also said something similar regarding a shoe you didn’t adapt. I was wondering if we run differently in different shoes or if it is the shoe that act diferently…

best regards,

Sergio (Brazil)

I often experience the exact same thing. Shoes can change you biomechanics,

often by altering muscle activation, and can stress the body in different

ways. Remove the heel and you can strain the Achilles. I also sometimes feel

plantar strain when I go back to a bigger heeled shoe. I’m convinced that

shoes play a role, and that each of us needs to find the shoe style that

works best for our body.

Pete

I’ve been trying to increase speed by increasing cadence, but I’m such an amateur runner that so far all it’s done is get me winded quicker! I was so concerned that I even had a pulmonary function test done, which came back just fine. Unfortunately that leaves me with the rather annoying conclusion that I’m just lazy LOL

In the mean time I’ll keep creeping forward and articles like this and the ones referenced are an invaluable resource. Thanks Pete!

Chris

About your comment on not being able to increase stride length past a certain point, i guess that point would be where you start to overstride. Usually for me, manipulating speed to below a regular (easy/ long run) running pace would just involve shortening my stride length. For tempo runs and intervals, however, I increase my stride rate as well. So I would say there is a limit to stride length up to the point where a full stride length x normal cadence = easy/long pace speed. Then to increase speed, I manipulate the cadence.

Great article by yourself and Steve Magness.

I do worry that new runners are taken in by ChiRunning and the like and get brain washed into believing everything these guru’s say.

So it’s great that Steve can show them up for the shysters they really are!

Thanks Rick. I actually spent quite a bit of time talking with Danny Dreyer

in Shepherdstown a few weeks back. Great guy, and he is genuinely interested

in helping people run injury-free. I actually took a one-hour workshop with

him, and the form Chi promotes is very much in line with what we are all

saying. The details of how we get there may vary, but I respect his approach

having now seen it firsthand. He basically advocating a midfoot stride,

landing close to the COM, and light steps. Nothing really wrong with that.

Pete

Although a great post, I was surprised that you didn’t mention the role of pelvic girdle and hips in “stride” related issues. I’d appreciate your thoughts on the role of our locomotion epicenter on over striding, stride length and stride rate.

BJ – I only commented where I felt I had something to add. Jay Dicharry does a nice job covering core/hips in his post linked at the top of this one.

Pete thanks for reply.

Danny may be a nice guy who like to make a lot of money out of innocent new runners.

My biggest problem with Chirunning is he claims to run faster you lean more forward from the ankles, to use gravity to pull you forward!!!

There is enough scientific evidence to show gravity only wants to pull you down and not forward.

I talked to Danny about a lot of these things, and he is very much a

teacher who uses cues to teach runners who often don’t know anything

about biomechanics. He understands that science may not sync 100% with

his cues, but if the end result is better form for a new or injured

runner, does it really matter?

Pete

On Tuesday, February 22, 2011, Disqus

Pete,

Great summary of what is known on this topic. As one who teaches this stuff to folks almost daily one big tip is to make sure runners do not force the cadence…but rather allow it to happen by optimizing the natural elastic recoil properties of muscle/tendon which is 175-185 in most folks. Hip extension is the key as is getting in flat footwear to allow the recoil of the Achilles to occur in this frequency. With the heel elevated the recoil is shut off and you must force the cadence and thus create more muscle activity.

With practice, good cues, and patience you will discover the magic of recoil and simply allow the motion of hip extension, foot placement, and leg return to happen. No active pawback; no forced lifting motion, hamstring activation, or foot placement; and a very gentle lean from the ankle (with caution not to bend at waste). Runners need to be strong in single leg stance to be able to do this and have the proper range of motion in hip extension and calf/great toe dorsiflexion. We do a pre-assessment on this “mostability”- joint mobility and stability for the efficient running motion.

Main inhibitors we see clinically….work on these areas if you have a deficit:

•Weak glut medius for hip stability

•Weak foot intrinsics

•A big toe that is bent in (hallax valgus)- cannot balance on one foot. This is caused by improper fitting shoes

•Lack of adequate calf flexibility

So get in perfect posture and balance, practice jumping rope, let you legs extend behind you and return by recoil, and let your foot land beneath you. This should occur in a really relaxed rhythm.

Mark Cucuzzella MD

Owner Two Rivers Treads Center for Natural Running and Walking http://www.trtreads.org

Mark,

As a runner, runners’ physical therapist and running coach…I agree with you 100%. I think we are overanalyzing the stride rate/minimalist shoe to the extent that we are ignoring fundamental weaknesses and imbalances that MOST runners have.

If we are beginning to talk about changing a runner’s biomechanics we must simultaneously address the weak areas and tight areas. I see inability to activate the glut-max and glut-med as a problem in almost all the runners I assess and coach. It’s not just weak gluts either, it is all of the hips stabilizers (internal and external rotators included).

Nothing about running form or biomechanics happens in isolation. We need to look at the whole picture for the individual.

Robin Judice, PT, CSCS

Pete: Nice stride rate data on yourself. I think it would be moderately more meaningful to draw a line from your stride rates at different paces to your best paces for classic distances like 5K, 10K, half marathon, and marathon. In other words, to see what your stride rate is at the distances that are presumably most important to you and most other road racers. Amby Burfoot

I agree Amby, hopefully I’ll be able to get some of this data this year. I probably wear the footpod in Boston.

Nice article Pete, a good resume of the various recent blogs on the topic as well as adding your own data and thoughts. I really should start up my own blog to add my own thoughts as well, but the amount of time that it might suck is rather daunting… so I thought I’d add to yours here.

First up, I believe the whole over-striding mantra being bad is wrong. I know what is being attempted to convey by saying over-striding but it really is confusing the matter as it’s focus is wrong – it’s not specific enough. Your pictures demonstrate this perfectly.

Have a look at the female and male heel strikers vs ryan halls. In particular look at the angle between the foot and the heel and the vertical. The angle is about the same for female runner and Ryan Hall – they are landing pretty well the same distance in front of their hips. While the male heel striker is landing closer to his hips – yet we’d all likely to conclude that he’s “over-striding”.

For me the import factor is the position of the knee relative to the foot and landing not the actual distance in front of the hips. I know you and Steve have brought this topic up before, but I think it needs to be shouted out once more, the problem is angle of the lower leg to the vertical not the how far you land in front of your center of mass. This needs to be repeated over and again as it this point has been lost in many of the posts.

A second point I’d like to add, and it’s related to the first is that landing closer to your center of mass, without other compensating changes, will result in higher loads during the landing phase as this has to happen to keep your balance – this is basic Newtonian mechanics. Think about balancing a stick with two weight on either end, if you move on closer to the middle you have to add extra weight to it and remove weight from the other weight to keep balance. This is such a simple point that has been lost in the land closer to your center of mass mantra, with all other aspect kept the same landing closer to center of mass results in HIGHER landing loads, completely counter to what the proponents of this mantra claim.

The “other compensating” is what is really important. How can the cue “land closer to your center of mass” lead to lower landing loads when the physics tells us the exact opposite will happen? My guess it’s the higher cadence is probably the strongest factor, and when given this cue runners shorten their stride and increase their cadence. My second guess is that with due to the shorter stride runners are also landing with a more bent knee. Both of these are great outcomes if… the runner actual employs them as a response to the cue. The cue itself is a still wrong though, landing close to the center of mass is not a good thing it makes things worse – it’s the higher cadence and landing with a more bent knee are crucial elements which will help runners.

I realise that slamming the whole “land closer to your center” of mass mantra as being fundamentally wrong is going to raise a few eye browse but next time you go for a run try out a few experiments to convince yourself. Just run on the level at a constant speed and constant cadence, then start landing closer to your center of mass but keep that cadence and speed the same. What do you have to do to keep balance? You have to start slamming your foot down to keep balance, the closer you move your foot to your center of mass the more force you have to land with. Now if you take this to it’s end point and land directly below the center of mass then you’ll need to hit the ground infinitely hard for an infinitely short space of time to keep balance… jay way to go Chi Running!

So… why does it matter that the “land closer to/underneath center of mass” is contradictory? If the majority of runners when using this cue do the right thing? Well I believe it’s important as sometimes the this whole fad can lead so many people to understand the way the world works and runner incorrectly. Even the some of the “scientist” involved in sports science are trumpeting this mantra without even mentioning the contradictory nature of it… if the scientist can’t get it right how would expect the rest of running world? Also how are we to make progress if almost everyone is happily focusing on the wrong things?

I believe passionately that we should be taking a grip of the crucial elements of what is the problem and teaching how to remedy this. We won’t see the wood from the trees until we start clearly marking out what is based on solid foundations and what is contradictory or false.

The cues we should be teaching are landing with a bent knee, with the knee over the foot – you can easily look down your knee on landing, if you can see your shin then you are landing with too straight a leg.

Why is landing with a straight leg bad? It will result in high landing loads as the your body pushes down through the bones, and a result in double peak in your GRF as when you knee pops out you’ll loose precious GRF as the different muscles start taking the load, so to compensate you have to generate more force on other parts of the stance.

What about cadence? I find using your arms as means of setting cadence the most effective. I find that phone app with metronome good for setting cadence. However, perhaps even cadence isn’t that critical to running efficiently and injury free… my guess is getting the landing phase right will cure most of the damaging aspects or poor running form as is the critical cue to single out over all else. Upping cadence will help, and as a cue may even help with sorting out the landing phase as a side effect (a bit like “land close to your center of mass” but not in any contradictory ;-).

A final note on cadence, I’m surprised that the aspect of height and cadence is never brought up and discussed. I believe it’s the angles of the various parts of the legs and feet that are crucial, rather than the actual speed of turnover. Given two runners moving at same speed, a taller runner at slower cadence will can have the same legs angles as a shorter runner at the higher cadence. Given the same angles the relative external forces all likely to be similar. I see no reason why we should expect a taller runner to run at the same cadence as a shorter runner to remain injury free.

“…the problem is angle of the lower leg to the vertical not the how far you land in front of your center of mass.”

“…landing close to the center of mass is not a good thing it makes things worse…”

OK, but…

Based on the five pictures provided, THE critical difference between Hall and the four “over striders” isn’t what’s happening with their forefeet and legs, it’s what’s happening with their right feet and legs.

At foot strike, note how high Hall’s right foot is in relation to the others. My guess is that this extension “loads” the foot and leg for the optimum “foot strike” as depicted by Hall’s left foot and leg. It appears that Hall employs what Mark is referring to below, a slight forward tilt from the ankle with full hip extension.

It seems that hip extension is THE key to efficient form, which when employed in conjunction with a slight forward tilt will result in a desired turnover rate and optimum foot strike.

“At foot strike, note how high Hall’s right foot is in relation to the others. My guess is that this extension “loads” the foot and leg for the optimum “foot strike” as depicted by Hall’s left foot and leg.”

Ryan’s right foot is higher than the rest because he’s running much faster, nothing to do with high extension. No matter what running form you have your foot will raise closer to your butt when you run faster.

Ryan will also likely to be using greater hip extension than the other runners, again for the exactly the same reason – he’s running faster. You can tweak how much rotation you have in your hips when you run, but the amount will naturally raise as you go faster. Using a stronger hip rotation may also help the follow through of the lifted leg which will in turn lead to the lifted foot going higher, but not by a huge amount.

The big difference you see between these pictures will be down to the Ryan doing sub 5 min/miles, while the rest may well be doing 8min/mile or slower.

Robert – making quantitative comparisons between foot location relative to the COM between Hall and the others is probably not the best way to do things. Better would be to compare within individuals between a gait with an extended lower leg and one in which the lower leg is vertical upon footstrike with some kind of repeated measures design.

If we hold thigh position constant (likely not accurate, I know), and bring the foot back by chopping stride and reducing reaching with the lower leg, this will result in the landing position of the foot being closer to the COM. You could flex the hip and extend the thigh further forward and still have footstrike further out front with a vertical lower leg, but this would also increase vertical osciallation of the COM, which is not efficient. The fact that footstrike occurs closer to the COM when increasing cadence has been show experimentally: link to journals.lww.com…

“Robert – making quantitative comparisons between foot location relative to the COM between Hall and the others is probably not the best way to do things. Better would be to compare within individuals between a gait with an extended lower leg and one in which the lower leg is vertical upon footstrike with some kind of repeated measures design. “

I agree a crude look at pictures of different individuals isn’t ideal, putting a series of runner on a treadmill and video and measuring loads as they try changes to gait and cadence would be ideal.. but there is only so much you can illustrate when adding commentary to a blog :-)

However, even without ideal test conditions, it’s pretty easy to see that Ryan is landing well in front his COM and as far if not further than most of runners shown in your pictures who would typically noted as over striding. It’s the lower leg angle that we are all using to determine that “over striding” is occurring, and mechanically I believe this is the appropriate way to look at it. While landing relative to the COM is the wrong way and the wrong cue.

“The fact that footstrike occurs closer to the COM when increasing cadence has been show experimentally: “

Absolutely, can’t agree more… My point in my comment above is that it’s the cadence that is important not landing the position relative to the COM. The reason why higher cadence typically leads one to landing closer to the COM when running at the constant speed, is that with a higher cadence you have a shorter time on stance and shorter time on stance means shorter distance covered on stance, the distance between the COM as consequence will be lower. This doesn’t mean that landing closer to your COM is a good thing, it’s just a by product of a higher cadence – the higher cadence and position of the legs is the important part, and the part that should be the focus.

I should add that cadence itself isn’t something magical either, the loads will only be lower if the amount of time spent on stance stance as percentage of overall time goes up. If you reduce time on stance quicker than you up your cadence then your loads will go up so even cadence isn’t the perfect cue for lower loads and reducing injury.

Personally I feel that it’s flexing of knee that is the critical part to reducing the landing loads, it’s far more universal factor than anything else – above cadence or foot landing type. It’s also good because it’s easy to measure – just look down your knee on landing, couldn’t be simpler, and the mechanics all fit cue as well, there isn’t any ambiguity – land with straight leg and you’ve got a problem that you need to fix, land with flexed are the loading will naturally be smoother. It works regardless of cadence, running uphill, downhill, in your nightgown.

Whereas using landing position relative COM as a guide to contradictory, if you don’t change anything else other landing closer to your COM you will have to introduce higher landing loads. A cue that is contradictory like this can’t be a good one. It’s the other things that are happening when runners use this cue that are the important parts that have to more compensate for this basic problem in the cue.

Teaching the important bits directly is what we should be doing not faffing around with cues that turn out to be contradictory when you analyze them closely.

I think we are arguing the same thing but in different ways :) There are

clearly lots of cues out there, and some work better than others, but

generally they arrive at the same positive end result. Some say to shorten

your stride or put your foot down faster, some say to increase cadence,

etc., but the end result is most likely going to be a landing with a bent

knee as you mention. My feeling is to use the cue that works best for you,

and that might not be the same for each person.

Good discussion. I maintain that the hips and pelvic girdle are THE keys to creating an efficient, safe, repeating stride. Not foot strike in relation to COM, cadence, or shoe type. Get the hips, particularly the hip extension right, and an optimum foot strike and desired cadence will follow.

I’m sure many will find this counterintuitive, after all when was the last time a research paper was written on the role of the hips in creating an efficient, repeating stride. Feet and legs capture our attention; it’s where we affix our $100+running shoes, and where most running related injuries occur.

Going forward, I think attention will shift to further up the kinetic chain and reveal the importance of our hips and pelvic girdle in creating an efficient, repeating gait. I suspect most elite coaches have been onto this for years. The rest of us will get there eventually.

“Good discussion. I maintain that the hips and pelvic girdle are THE keys to creating an efficient, safe, repeating stride. Not foot strike in relation to COM, cadence, or shoe type. Get the hips, particularly the hip extension right, and an optimum foot strike and desired cadence will follow.”

I’m curious, what makes you believe this is might be the case?

Personally I can’t see a mechanism in which what you do with the hips as being critical to getting the overall gait efficient or lower impact. What we do with the hips will make a bit of difference to how will distribute forces, but this will be a secondary important to the parts of the body that generating all the big forces. The big forces all come from foot and leg placement through the stance.

What I would expect in order of importance would be knee angle on landing, then cadence, then lateral motion, then foot position, balance of the upper body and then hips. We might tweak the ordering depending upon what problem areas that a runner is particularly poor at , but I would expect this order to be a reasonable order to work on.

I would suggest the knee angle is most important as it’s the joint with greatest ability to tune the rate of loading. If you land with a straight leg then the forces can be introduced so rapidly that hips will be overwhealmed and collapse a little and rotate horizontal prematurely. Landing with bent knee will result in the loads raising slower and giving the hips greater time to handle the loads and be more square when the peak loads come in. Applying greater or less forces through the hips on landing won’t fix impact problem, bending the knee will.

In the interest of full disclosure, I have no professional affiliation with anatomy & physiology in any way. I’m not an elite runner nor do I coach runners of any ability. I suspect I’m like most runners; I’m prompted to new insight by new injury (running is THE classic “school of hard knocks”).

My injury du jour is a wickedly persistent hip/ITB/calve issue which has resulted in considerable research and professional consultation. The take away from this latest injury is that all locomotion in the lower extremities begins and ends in the hips – not in the feet, knees, or legs (resist the temptation to take exception until you finish reading).

As noted earlier, I think future research will indicate that healthy, well-functioning hips are THE key to creating an efficient, safe and repeating stride.

My research indicates that forward horizontal movement is caused primarily by the “unloading” or “unwinding” of the hip extension, and not the result of “pawing” or “pulling” the feet to the rear. Hip extension “loads” or “winds” the leg, forward thrust results from “unloading” or “unwinding” the leg as it moves through the stride.

I understand some may find this counterintuitive, so please do three simple things before dissenting.

One, watch Coach Jay Johnson’s video of Sarah Vaughn performing “donkey kicks” in his “Myrtle Routine” link to runningtimes.com… (click on “General Strength Exercise Video Series”, then click on the first video “Running Times: Part 1”, and find “donkey kicks” at @ 2:50).

Watch it several times, and then try a few sets on each leg. Sense the hip “loading” or “winding” the leg as it extends to the rear, and then sense the forward thrust as it “unloads” or “unwinds” while moving toward the chest.

Next, watch Ryan Hall’s stride several times link to youtube.com… He packs quite a wow factor doesn’t he?! OK, after you’ve picked up your jaw, do you see well-executed donkey kicks in each stride?

Lastly, try it yourself; try several short runs at a slow pace that allows you to focus on your hips in each stride. In your mind’s eye, try to see Hall’s and Vaughn’s hip extension.

Note your knee flex and foot strike. Over striding? Probably not, it’s almost impossible to over stride while focused on executing hip extension. It’s as if your feet just drop where they should, at the end of the stride – beneath your flexed knees (envision Hall’s foot strike). Also note how a forward tilt from the ankles encourages your hips to work more efficiently (open to the rear and thrust to the front).

I think this is what Dreyer and others (i.e. Newton, VVF’s advocates) have been saying in so many words. Admittedly it’s quite awkward at first, a bit like a baseball player or golfer trying to re-engineer their swing, but when I find the sweet spot, there’s a sense of running efficiency like I’ve NEVER experienced.

Hi BJ,

Thanks for the links, interesting watching. Save for a few occasional bouts of calf exercise I’m afraid I don’t do any strength exercises… Um.. perhaps I should be adding a few. Kinda just love uncomplicated running though.

With the exercises videos and the video of Ryan Halls stride I didn’t see anything that struck me as hip extension being the core mechanism that we should work on. The donky kicks were just one of many routines, and Ryan’s hip extension wasn’t particularly prominent, or his gait different than I’d expect a world class athlete running sub 5 min/miles.

From time to time I play around with various aspects of my gait during running and hip extension is one of the parameters I play with. Hip extension is something I’ve come to view as an integral part of the running gait rather something as uniquely deserving of attention.

I must add that I’ve only had injuries in my lower legs – my feet, Achilles and calves. I am probably quite lucky in that a efficient running gait has come easily, seemingly a default setting for my body. Injuries I’ve had have been down to footwear problems or ramping up the miles too quickly.

Robert,

One additional area where the hips are important is in terms of proper

balance between strength of the adductors and abductors (e.g., glutes). Weak

glutes can lead to problems with thigh positioning in the frontal plane,

which can cause any number of problems from hip pain to ITB problems. My

take is that it’s a mistake to focus on any one part of the lower extremity

in isolation from all of the others.

Pete

Good point Pete, imbalance in strength of the muscles connecting to the hips will lead to problems at the hips elsewhere.

I am becoming curious about the role of soft tissue and bone development in response to training and how poor gait at the beginning can lead to imbalances in strengthening of various parts of the body – with the imbalances leading to injury as weaker parts are overwhelmed or lead to over stress in other parts of the body. Even with a healthy gait imbalances seem to occur as well as different parts of the body seem to strengthen at different rates.

One of my experiences with getting back into running over the last two years is that I’ve had injuries that I was convinced were due to problems with my gait. In hindsight the gait wasn’t the problem – footwear and ramping up the miles/insufficient recovery was.

Recording slow motion video would have been useful, as would have testing my cadence earlier, both would have probably have told me earlier that my gait was fine, and not at all the place to look for the cause and cure of the injuries I’ve had. With all the different advice and many cues it’s hard to know you are doing things correctly, it’s all too easy to assume that you are still doing something wrong, even when you aren’t.

I recall two points last year when I separately had concerns about over-striding and cadence. The time when I put the over-striding demon to rest was when I ran perpendicular to a sun that was low on the horizon – finally I got to see my side profile as I was running, rather than my foot being too far into of my knee it was landing below or behind. At this time the trick of looking down ones knee as a visual cue for detecting over-striding occurred to me.

On the cadence front I was convinced by my niggling injuries were likely down to too slow a cadence, so I downloaded a metronome app for my phone to my surprise my cadence was just fine. Putting this one to rest meant that I could focus on the areas that were really causing problems.

For me kicking my injuries to touch has involved dumping heavily cushioned shoes, making sure shoes are wide enough to accommodate my wide mid foot and taking proper rest when parts of my body are showing signs of over-use. I’m now 6 months into an injury free period ;-)

At one point I was convinced

I’ll pitch in another ideal that might be controversial and hopefully get others to think about the topic in a possible a new light ;-)

I believe landing flat footed might be the worst type of landing for reducing loads on the legs and the rest of the body. Landing on the heel will actually reduce loads in comparison to this, as will landing on the forefoot and then lower the heel will also reduce loads compared to a flat foot landing.

To test this out yourself stand up straight and then let your body fall forwards and then put out one straight leg to arrest your fall, lock your need to make sure all the loads go directly into your hips. Do this test three times, first land on your heel as you’d do when walking and let your foot rotate over naturally as you would when walking. Next land flat footed. Next land on your forefoot and let you heel down smoothly. Note the impact forces that are pushed up into your hip on each type of landing.

So if you’re like me you’ll find the flat footed landing the most solid of all the landing types, landing on my heel is second best, while landing on my forefoot and letting my heel down is the most gentle and smooth. It’s the ability to rotate the foot when landing on the heel that affords us a little reduction in loads over the flat footed landing.

With this observation, we can look back at the pictures and see that heavily dorsiflexed is a natural mechanism for reducing loads that we’ve all learnt from walking. Perhaps heel strike is not a cause of problems but a symptom…

Just look higher up the leg and you find the unbent knee, the classic straight legged pose of heel striker. A straight leg is appalling at applying landing loads smoothly – you might have just done this test to prove it, so the body has no place to mitigate the loading other than introducing heel strike.

Go back and the do the test with a bent knee and try all the landing types out. I’ve found that all foot positions on landing now become comfortable, even the flat footed one! It has become far less critical how I land – as long as I land with flexed leg the forces are all introduced smoothly.

Perhaps this goes some way to Jay Dicharry’s recent blog entry “Loading Rate: Part 2: Forefoot, midfoot, rearfoot……..Who cares?”. Personally I do care about landing, and much prefer to land on gently of my forefoot with my knee over my foot, it just more efficient – elastic recoil is maximized with forefoot landing. But I can’t argue that it’s possible to land safely on your heel. Jay’s findings suggests that some runners are able to land on their heel with a smooth onset of loading, and my crude little landing experiment illustrates it too.

Interestingly Jay’s article picks out a runner who lands mid foot as one who contrary to usual expectations suffers from a high loading rate… but perhaps this finding shouldn’t be too surprising given my little experiment with landing flat footed suggests that off all landing types it’s the least forgiving to problems in the rest of your gait.

Pete, Ref; Danny and Chi Running ; Yes the truth dose matter!

In his chi running video the first thing you see is a waterfall.

Danny tells us the viewer that we can tap into this energy ‘gravity’ by just leaning forward!!!!

He is telling untruths in scientific rubbish!!!

I’m sorry Pete but I don’t understand as a scientific person you can support his claims?

Literal truth is for pedants. What really matters is how thinking affects performance. I find the mental image of a waterfall to be both simple and useful, despite its lack of scientific rigor. The ‘truth’ that matters most to me is running well, with maximal comfort and minimal damage. Any image that helps me get my body to do that is ‘good’.

“Literal truth is for pedants.”

So a let a pedant parse this sentance… Literal meaning in this context is true;actual (item 5 on http://www.thefreedictionary.c…. So… “Actual truth is for pedants” is probably what you mean, or is it…

And pendant is “something suspended from something else, especially an ornament or piece of jewelry attached to a necklace or bracelet.” (http://www.thefreedictionary.c…

So put this together and we have “Actual truth is for a collection of jewelry handing from a necklace or necklaces”.

Of course I knew what you actually meant… You mean to be derogatory towards those who seek out the actual truth.

Part of seeking out the actual truth and also means expose falsehoods – and this is probably why Rick’s comment made you feel the need to be derogitoary.

Enlightenment is a journey that involves exposing falsehoods and seeking the actual truth. It’s a noble yourney that does involve the discomfort of friction internally against your own misconceptions and against external dogma’s that cloud our judgment. You have to push through this to reach Elightenment.

Alas Chi Running contains major falsehoods as well as nuggets of wisdom so is a confusing path to follow. The falsehoods are your can use gravity to propel you, while the reality is that you have to going downhill for this to happen. The reality is that 99% of the external forces on our bodies when running is fighting the effects gravity and trying to do this efficiently and with least injury as possible. Gravity isn’t a friend that you can utilize, it’s the beast this our greatest foe.

Another serious falsehood is that you should land under center of mass. This is physically impossible save for when accelerating or pushing into a very strong wind. To land under your center of mass will cause you to fall flat on your face, it the essence of unstable system.

Another falsehood is that Chi Running will teach you to run like a child again. Young children don’t Chi Run, they land on their forefoot, and end of the stance push off strongly, they have a great love of speed, there is no gently jogging, its all out glee with the sheer joy of flight at full speed. Chi Running is a shuffle by comparison and has nothing to do with how young children run and will never teach you to run like a child again.

All these falsehoods tell me that Chi Running is not Chi at all, it’s lost it’s way on the road to enlightenment. I’ve done Tia Chi and from what I took away from it’s about economy of motion, balance and working with the forces of nature not redefining them in ways that are impossible.

Danny Dryer would be wise to shake off these falsehoods and restart his journey to a greater understanding of running form and how the physical world works around him. He is both a great and flawed teacher, but like all of us has the capacity to move on to a greater understanding of the world. He will become a greater teacher once he bathes in the light of “Literal truth”.

I would suggest that you don’t dismiss those that you see as pedantic, there are the ones seeker the “Literal Truth” and not compromising for an easy life. The struggle for enlightenment isn’t always a peaceful one.

Two thoughts:

1. Why is it important to emphasize cadence? Because it is HARD to change!

Increasing run cadence is difficult: The timing of firing many muscles has to change and become smoothly coordinated. This is vastly harder to do than a change to stride length (at a constant cadence), so a corresponding difference in emphasis is totally warranted.

2. Why minimalist shoes? Because they are LIGHTER!

When I switched from my ‘stability’ running shoes to racing flats I lost HALF A POUND of weight from each foot! This immediately took 30 seconds off my (admittedly slow) running pace. Weight loss can improve performance in all athletic endeavors, and for running it is most useful to go from the bottom up!

Peter,

I’m am curious about the relationship between breathing rate, cadence, running intensity/pace. You have data on cadence and pace, and your observations about what happens with your cadence with pace are similar to what I guess happens for me, but I don’t have the data to correlate…

Anyway, the thing I’m particularly curious is the whether there is a step change in cadence as we run at higher intensity, if so might this be in some way related to our breathing pattern as we naturally will try and sync our breathing with our stride.

Thoughts? Observations?

Robert.

Robert,

Never paid much attention to my breathing, except that I find that it is a

better indicator of effort late in a marathon than heart rate. I should pay

attention as I play around with my cadence – too many variables to consider!

Pete

Pete, I love how you’re pulling all this stuff together in one place. One stop shopping for info here at runblogger. Cheers.

Thanks Mark!

I would like to comment on this because I started trying to take up the pose running method a few months back which stresses the increased cadence and forefoot landing. I bought the Kinvaras in November in the middle of training for the Disney Marathon, but got tendinitis in my right foot shortly after (a few days… I don’t think it was the shoes, though perhaps the quick switch from my stability shoes + orthotics might have been a bad idea). I tried to work on landing on my forefoot on my own, but didn’t quite master the faster stride rate. I went to my physical therapist, and he gave me the usual exercises to try to fix my biomechanical issues, and then I mentioned the Chi Running method to him since I had the book. Well, he seemed to think it would be a great idea for me to try something different and watched me run and gave me some pointers on the pose method. I started working on the techniques during my runs and noticed the pain going away. When my tendinitis was acting up, I noticed that it was when my stride was slowing down/I was landing wrong, so I changed my stride rate and the pain went away.

My calves were definitely in some pain for awhile, and I was a little concerned that maybe I was developing something in that area, but once I got the hang of the technique, I ran much faster (about 30 seconds per mile faster without extra effort), and my pain is gone today after my 11 mile run yesterday (the longest run I’ve been able to do since I got tendinitis). I feel great when I run – very light. I guess that’s not so much a scientific comment as an observation and testimonial. Of course, it may not work for everyone, but I struggle with injury, so trying something new seemed worthwhile. So far I’ve found the faster stride rate and forefoot landing to be incredibly helpful. Though I realize this would probably belong in your review on the Kinvaras, I’m going to say it anyways: I love the Kinvaras!

Thanks for the note Nina! That’s my exact point – if a method helps someone

to run pain free, then by all means go with it. Chi has clearly helped a lot

of people, and I give Danny Dreyer much credit for that.

Pete

Pete, You do a fantastic job with your sight. I’m a little late in responding to your stride rate, frequency article since I am reseraching that area at the present. Dr. Tim Derrick, Iowa State has written extensively about the effects on shock attenuation during running. His studies, that we are validating now suggest that lower extremity stiffness varies with geometry and changes that alter impact magnitude, such as greater knee flexion. Research in our Lab concur with Dr. Derrick that when velocity is kept constant, skock disperion increased with stride length and decreases stride frequency. However, muscle forces required to change stride frequency also need to be considered in affecting shock absorption. We have found that runners have a preferred optimal natural resonance or frequency that they attempt to maintain, but is altered by their fitness level and fatigue. These alterations in muscle optimization and geometic alterations may be the true culprits related to overuse injuries. How only can we maitain efficiently running form before things start to break down? More will be revealed. Long May You Run!

Ray Runs Wild

Ray Fredericksen M.S Biomechanist

Sports Biomechanics, Inc.

Haslett, MI 48840

517-230-2472

2. Adopting a running form is a good idea, however, I don’t honestly believe that a runner will be able to possess a new form in a short period of time. I’m looking at Pete’s idea of shoes changing biomechanics – seems legit.

“For me the import factor is the position of the knee relative to the foot and landing not the actual distance in front of the hips” – Sorry Robert but this is just plain wrong-otherwise we would be advocating “running lunges” and even at a slow running pace, that would cause a serious amount of overuse injuries very quickly.

This is an excellent post! It consolidates everything I have been reading recently on the same topic. And I agree that shoes do play a vital role and that each of us needs to find the shoe style that works best for our body and run form.