I just read an interesting article by Matt Fitzgerald titled “The Barefoot Running Injury Epidemic” about the rising tide of barefoot running injuries (article published on Competitor.com). In the article, Fitzgerald indicates that various medical professionals (physical therapists, podiatrists, etc.) are reporting seeing increasing numbers of patients who are suffering injuries thought to be directly related to running barefoot. I’m not surprised in the least by this, as a simple perusal of almost any barefoot/minimalist running forum will typically turn up multiple people complaining of various aches and pains (some serious, some less serious) related to starting to run barefoot or in minimalist shoes like the Vibram Fivefingers.

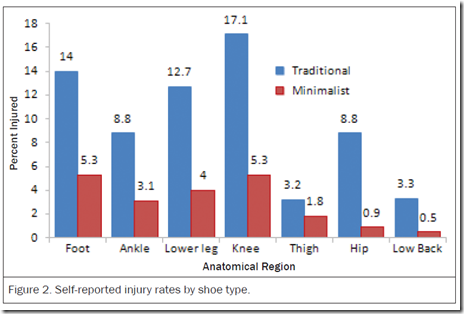

While the reports in Fitzgerald’s post are anecdotal (we really need some hard data!), I have no reason to suspect that the rash of barefoot running injuries isn’t real. In fact, I myself even dealt with some unusual pain on the top of my foot after my first overly exuberant run in the Vibram Fivefingers last summer (during which I tried to force a forefoot strike for over a mile – very bad idea). This initial scare led me to shelve the Vibrams for a few weeks before working my way back into them much more slowly (I now run regularly in Vibrams with no problem). I’d speculate that a majority of the injuries being seen are related to people jumping on the barefoot/minimalist bandwagon and overdoing it with mileage to the point where their bodies can’t adapt quickly enough to the new repetitive forces being placed on them. This is a recipe for disaster, and ligament/muscle damage and stress fractures are an unsurprising result (I should note that this is likely not unique to barefoot running, and could equally well apply to switching to a new style of shoe).

I’d also agree with Fitzgerald’s point that some people simply aren’t suited to run barefoot, and there are probably an awful lot of “Jim Hogarty’s” out there (if you haven’t read Fitzgerald’s article, Jim Hogarty is a pseudonym for a childhood friend who couldn’t run). So given all of this, I’d say I’m mostly in agreement with almost everything Fitzgerald wrote in that article. I believe that barefoot running can and does cause injuries (just as shod running can), that it must be adopted with caution and care, and that there a certain number of people who simply should not do it due to underlying biomechanical problems. At the same time however, I see no reason why someone shouldn’t try to run barefoot to see if they like it, and keep doing it if it works positively for them. As long as it’s done carefully (not too far, not forcing anything like I did with the forefoot strike in Vibrams), I suspect most people who try barefoot running are not going to horrifically injure themselves. I’ve tried running barefoot on asphalt twice myself, only to decide that it wasn’t for me, but I have run 100+ miles in my Vibram Fivefingers with no problem since that very first run.

The one major point where I do tend to disagree with Fitzgerald is regarding his take on the evolution of distance running in humans, and this stems mainly from the fact that I myself am an evolutionary biologist. In his article, Fitzgerald states the following:

“…humans really are not born for distance running in the same way that cheetahs are born for sprinting. Evolutionary biologists other than Daniel Lieberman will tell you that humans are born generalists more than we are born specialists in endurance running or anything else. A natural consequence of this “jack of all trades, master of none” design is that there are different types of individual specialists within the total human population. Some of us are strong, others weak. Some of us have great hand-eye coordination, others don’t. Some of us can be great marathon runners, others can’t run a step.“

There are a number of problems with what is stated here. First of all, who are these “evolutionary biologists other than Daniel Lieberman” that he mentions? I’m sure they’re out there, but why shake the finger at Lieberman’s theory without backing it up with some names, citations, and/or quotes?

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaSecond, the cheetah example is a poor one. Natural selection has molded cheetahs to be excellent sprinters so that they can catch equally fast prey, and this is more or less what they still do in the present-day environment. If a cheetah were a poor sprinter (now or thousands of years ago), that individual would die and not pass on its genes. In other words, it would be an evolutionary dead end.

Following on this, you cannot compare the human population of today with that of our distant ancestors. I suspect that variation within early human populations was far smaller than it is today, and I personally find Lieberman’s distance running hypothesis to be entirely plausible. Early humans had to be able to find and catch prey, and if they couldn’t do it well, they would have died out. In other words, if you buy Lieberman’s persistence hunting hypothesis, early humans had to be able to run well to track and kill prey. There could very well have been subdivision of labor among individuals as Fitzgerald suggests, but I’m not sure that we’ll ever know that for sure with any greater degree of certainty than we’ll know if Lieberman is correct.

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaIn contrast to the above, modern humans rarely if ever have to run for our survival. We don’t need to hunt and gather our food, and the nearest supermarket is typically only a short drive away. In fact, millions of largely sedentary individuals manage to reproduce every year, so there is no longer any selective pressure for a human to be well adapted to distance running. This doesn’t mean that our species didn’t evolve to be excellent at distance running, it just means that we no longer need this skill and deleterious traits that impede our distance running ability have managed to filter through the human population. So it’s quite possible that the human species evolved to run, but that many modern humans are not born to run in any way, shape, or form (barefoot or in shoes!).

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaPerhaps the better analogy here would be to look at dogs. Modern dog breeds are descended from the wolf, which by all accounts is a fantastic distance/endurance running animal. However, most dogs nowadays are domesticated and don’t need to chase down and kill other animals in order to eat. Nobody would think to take a chihuauhua for a 20 mile run, or a bulldog for a speedy interval session. Just as some human individuals nowadays are built to run well and others are not, some dogs are better than others at distance running, and some possess traits that make them poorly suited to running at all. So with dogs we have an example of a species that evolved to run very well, but nowadays consists of highly variable individuals, some of whom are better suited to running than others. Is it not possible that the same type of situation could apply to humans? What if, like dogs, we descended from a much less variable population of excellent distance runners, only to have inactivity, medical advance, and modern convenience lead to a loss of this ability in at least a portion of our population? If this is the case, then maybe some people can run barefoot just fine like our ancestors did, but maybe others need a bit of corrective help along the way.

I’ll finish with this – it is for the above reasons that I find the following statement made by Fitzgerald to be frustrating: “The romantic vision of an Edenic primitive humanity in which everyone ran like Kenenisa Bekele is complete hokum. Endurance running was very likely only ever a specialization of the few, exactly as it is today.” How does he know this? Maybe there are data out there supporting this contention (I’m not an anthropologist, so I don’t know the relevant literature), but a statement like this really needs to be backed up beyond simply referring to “evolutionary biologists other than Daniel Lieberman”. Lieberman has provided a bunch of evidence to support his distance running hypothesis (both anatomical and physiological), and it takes more than an unsubstantiated throwaway statement like this to shoot that down and call it hokum.

If you like this post, you might be interested in the following Runblogger blog posts and podcast episode:

Blog Posts

1. The Barefoot & Minimalist Running Debate – A Plea for Moderation

2. Barefoot Run #2 – Much Better, But Still Not Sold on Barefoot Running

3. Barefoot Running: Thoughts on My First Barefoot Run

4. The Evolution of Running in Humans: Why We Are Meant to Run

Podcast Episodes

1. Runblogger Podcast #7: The Evolution of Distance Running in Humans

2. Runblogger Podcast #9 – Minimalist Running

3. Runblogger Podcast #16: Barefoot and Minimalist Running: A Word of Caution

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1afb1707-2879-4ad7-b6ff-878f0c59baf0)

The invention of cars is only on the order of 100 years, as is industrialisation which is chiefly what allows a modern sedentary lifestyle as you describe it. In terms of human lifespans, it accounts for at most 10 generations which is insignificant for any kind of evolutionary change in the species. I don’t know the statistics but cars must be in use by far less than 50% of the world’s population as well. In terms of changes in evolutionary pressure humans, I think you’d have to compare conditions which have persisted for at least several hundred, if not thousands, of years.

That said, I think it’s immaterial whether man is evolved to run. Anyone who has a choice to run barefoot or shod is doing it for pleasure. I also think injury prevention is a red herring. Maybe barefoot running should be considered on its own, as an independent sport, like say, trail running or mtn biking. Do it if it’s fun, with care and some thought. It doesn’t have to be as dogmatic as people like MacDougal and Fitzgerald make it seem.

Elodie,

I think the more relevant advances were the advent of agriculture and domestication of food animals, which have been around for 1000’s of years. These permitted humans to stay put and relieved the need for activities like persistence hunting and scavenging for food. This in turn means that distance running ability was probably no longer as strongly selected for, but we retain the general anatomical and physiological adaptations that make our species great at endurance running (with lots of variation).

On top of this, some of the factors that make running hard for people nowadays are lifestyle related – years of inactivity weaken our bodies to the point where they are no longer suited to the activity, and a lifetime of wearing shoes acclimates our feet and legs to this condition as well. It takes a long time to reverse this, and some may never succeed in doing so. These latter factors are outside of evolution, but may be just as important, and few would argue that people who grow up in societies where running throughout life is the norm are far better at it than most of us in modern society.

Pete

Elodie,

I think the more relevant advances were the advent of agriculture and

domestication of food animals, which have been around for 1000’s of

years. These permitted humans to stay put and relieved the need for

activities like persistence hunting and scavenging for food. This in

turn means that distance running ability was probably no longer as

strongly selected for, but we retain the general anatomical and

physiological adaptations that make our species great at endurance

running (with lots of variation).

On top of this, some of the factors that make running hard for people

nowadays are lifestyle related – years of inactivity weaken our bodies

to the point where they are no longer suited to the activity, and a

lifetime of wearing shoes acclimates our feet and legs to this

condition as well. It takes a long time to reverse this, and some may

never succeed in doing so. These latter factors are outside of

evolution, but may be just as important, and few would argue that

people who grow up in societies where running throughout life is the

norm are far better at it than most of us in modern society.

Pete

Sent from my iPod

Reading Fitzgerald’s statement “Every cheetah is a world-class sprinter.” i’d have to correct him. Every “living” cheetah is. Those less qualified are the rotting carcasses who couldn’t support themselves by hunting. If humans wouldn’t live in a world where we don’t have to run for survival, Fitzgerald would have never met John Hogarty, because John would have never lived to go to elementary school. It’ll take a little more than that to prove that humans are not born to run, but i guess Fitzgerald does know that.

Anyways i see the point (and i’ve seen it being made elsewhere) Fitzgerald and Pribut are trying to make: “Everyone is reading Born To Run and wanting to run barefoot”. McDougall’s book is a fascinating read but as with Fitzgerald’s article the general rule applies: Don’t believe anything you read. You’ll find statistics, studies and scientists to back up anything you say if you search long enough.

After i read the book, i thought about it and i am trying to incorporate minimalist shoes and barefoot running into my training ever so slowly with the main focus on listening to my body. What changes? How does it feel?

And i could imagine that’s the problem right there. In a society where people want a quick fix for anything i could imagine people read about barefoot running, try it and hurt themselves. Of course they are told to take it easy at first, but what does that mean? And are the rules if there are any the same for everyone?

I think people are too disconnected from their bodies. If you’ve listened to your body long enough, you can tell if somebody moved the saddle on your race bike just a little bit or what heart rate you have even without a monitor. It’s that sense for your body that prevents injuries. Knowing when to stop and what to do next. In twelve years of endurance sports i haven’t seen a doctor once about sports related injuries. And it’s not because i was blessed with a perfect body – my spine is twisted and my hips ain’t perfect either.

So even if somebody was with the Tarahumara or is a senior editor for any group, my take is to get inspired by all the information, don’t let it confuse you and think for yourself.

Thanks for the comment – I agree completely with you here. Your point

about being in tune with your body is an excellent one!

pete

The first paragraph of article says it all –

“Fogt says he has four or five current patients with heel injuries clearly resulting from a switch to barefoot running and has recently treated another 12 to 15 others.”

heel strike

Martin,

It’s tempting to suggest that these injuries were due to people

running barefoot with improper form (ie heel striking), but it’s worth

pointing out that the plantar fascia extends from the calcaneus on the

base of the heel to the metatarsal heads. Thus, it Is plausible that a

forefoot strike could generate tension in the plantar fascia and

strain it’s attachment at the heel. This could cause heel pain in a

forefoot striker. Without knowing the details about these injuries it

is impossible to say what’s going on – that’s the problem with

anecdotal evidence, and why we need some hard data on this issue.

Pete

I had some transient PF when getting into barefoot-style running. Really just a little tightness in the mornings. And it disappeared as I progressed, no Dr’s visits required.

I suppose you could push that into a full-on PF outbreak. I’ve heard of more people curing their PF using barefoot-style running, however.

And I have a lot of trouble believing this is an “epidemic”. Vibram is selling a good number of their shoes, but I don’t know what people are doing with them. They’re pretty clearly not going out and running, or running races.

People wearing Vibrams or running barefoot are still an absolute rarity. It’s tough to have an epidemic if no-one has the disease. ;)

Tuck,

It is odd that Vibrams seem to be selling like crazy, yet I almost

never see people running in them, or even wearing them out and about.

Excellent points!

Pete

Sent from my iPod

Martin,

it’s tempting to suggest that these injuries were due to people

running barefoot with improper form (ie heel striking), but it’s worth

pointing out that the plantar fascia extends from the calcaneus on the

base of the heel to the metatarsal heads. Thus, it Is plausible that a

forefoot strike could generate tension in the plantar fascia and

strain it’s attachment at the heel. This could cause heel pain in a

forefoot striker. Without knowing the details about these injuries it

is impossible to say what’s going on – that’s the problem with

anecdotal evidence, and why we need some hard data on this issue.

pete

From a practical standpoint, I believe most modern runners should do some form of barefoot or minimalist running. But the majority of the benefits (increased strength, efficiency, injury prevention) from barefoot running can be realized with just a few modifications to a standard training plan. Throw in some barefoot strides 1-2 times a week, run workouts in racers/spikes, and stay barefoot in your home – that’s practically all you need! There’s no reason to be a 100% barefoot runner or someone who clings to their Brooks Beasts. Barefoot training is a spectrum, and one that most runners would be wise to stay in the middle of.

That’s basically what I do – run in Vibrams or other minimalist shoes

once or twice a week to work on foot/leg strength and form. I use a

spectrum ranging from the Brooks Launch down to the – seems to work

well for me.

Pete

Nice post.

The Fitzgerald article is just news hype written to generate traffic to their website. He acts like nobody ever got plantar fasciitis before running barefoot, which is laughable. The best way to get traffic on the Internet is to post something incorrect or inflammatory. All the concerned individuals will arrive to point out the errors.

Great post! I’m very much for barefoot and minimalist running, but I suspect a lot of people are jumping into it to hastily and completely unprepared. As a result, they are risking injury unnecessarily.

I think your response here is very reasonable and share many of the same concerns about Fitzgerald’s post that you and otheres have pointed out here.

While I am not convinced that we have enough evidence to say that barefoot running increases injury or is actually better based on the data we have at this time, my concern is that the fanaticism surrounding barefoot running will lead to rejection of any actual data that suggest that certain runners may be at high risk for injuries. This article is one of the few I’ve encountered on the topic of barefoot running that suggests that people may need to ease into this practice or that it may not be for every runner. Thanks for your balanced response.

That’s a really good, well thought out analysis of his article. I don’t, nor do I have any interest in ever, running barefoot. I do wear Newtons, I am a forefoot striker, and I am a relatively fast distance runner for my size. I’m 6’1, 200. The statement about being made to run is B.S., I concur with your analogy. The rise in barefoot injuries has to be proportional to the rise in amateur barefoot runners. Vibrams are everywhere. I ran a 4 mile off road event where runners were finish up at 12 minute miles wearing these shoes. There is your problem.

I have said before that the less shoe I have on the better I run and the better I feel but it took me 3 months to work into my Newton shoes, that’s after 14 years of running.

Good write up man.

Joe

Joe – exactly! Try as we might, we runners are often quick to jump on

a new trend (I’m just as guilty as anyone on this), and with barefoot

and Vibram running this can lead to major problems. Do it slowly and

carefully, and most people will probably adapt just fine.

Pete

Hi Peter,

If you are an evolutionary biologist, then maybe you can sort out my concerns, as I have stronger doubts regarding Matt’s dismissal of Lieberman’s theories.

They way I learnt it, for a trait to become universal in a species, it is enough that it provides a sufficient survival advantage to the bearer. Of course if missing that trait condemns you to oblivion, then it will work its way to supremacy much faster. But that’s not a necessary condition.

Why do Europeans have light skins and Africans dark ones? Because there was some advantage to it: maybe vitamin D synthesis for ones, maybe not getting sunburns in the other. Not a vital one, since black people live with no problem whatsoever in Europe, and there are whites living unharmed in the tropics. But if you add up a small advantage over thousands of generations, then you basically get a population which is very much optimized, and the optimal trait becomes universal. Lactose intolerance would be another example: virtually all Zambians are, virtually no Danish is. Is it a vital characteristic for survival? No, but it certainly is an advantage to digest cow milk if it is available. SO where it is, it becomes almost universal.

So I would think that, even if cheetahs were generous souls that shared part of their prey with the Jim Fogartys among them, you’d still expect the vast majority of cheetahs to be blazing fast. Because over the millenia, the slow runners would be the first to go when there was scarcity, so their genes would eventually be washed out of the population.

Same thing applies to humans: if persistence hunting was the main source of food for our antecessors, even if they took care of the weak, you’d expect the vast majority of humans to be good runners. Maybe not Bikilas, but definitely not Jim Fogartys.

And then we come to the end of the selective pressure, with modern civilization. So there may not have been any incentive to be a good runner over the past 10,000 years, but does that mean we, as a species have deconditioned for running? I greatly doubt so. Again, take lactose intolerance. Virtually all Zambians are lactose intolerant. Does digesting cow milk put you in any way at disadvantage if you live in Zambia? Doesn’t seem likely. Are the Danes more likely to get mutations than the Zambians? Not likely either. Why then hasn’t the lactose tolerance gene spread over a considerable proportion of the Zambian population? Because there’s no selective pressure for it either, and deleterious mutations come and go, without ever becoming predominant.

So even if running is not an advantage nowadays, unless not being able to run has turned into an advantage, it is extremely unlikely that the majority of us will lose that ability, unless we let evolution work for several hundred thousand years, when it is very likely to have turned us into a different species, where other abilities may have taken over the preceding ones.

Oh, and dogs are a very bad example: there is a very strong selective pressure on chihuahas to be small. The large chihuahas are simply not allowed to breed by their owners. So traits become predominant much, much faster. If a mad eugenicist allowed only the Jim Fogartys to breed, then humans would likely turn into non-runners in only a couple of centuries…

Jaime,

I’ll try to address a few of your points.

1. Skin coloration is similar to running in that our current environment is very different than the one in which those color variations appeared. Nowadays, light skinned people can live safely in the tropics because we can stay indoors during the day, apply sunscreen when we go outside, and have skin cancer treated effectively in most cases if we happen to develop a tumor (i.e., it doesn’t kill us most of the time, except if untreated or is something like a nasty malignant melanoma). Many of these options were not available to our distant ancestors. It’s also worth noting that Australia has one of the highest rates of skin cancer in the world.

2. Don’t get me wrong, I tend to believe Lieberman and Bramble’s hypothesis that the human body evolved to run. All humans share most of the significant traits that make us great runners that they identified – little body hair, sweat glands widely distributed, springy tendons in legs/feet, big gluteus maximus, nuchal ligament, etc. These are the traits that were likely heavily selected for in our ancestors. What we have now though is a much, much larger population of humans that is likely far more variable on that basic body plan than our ancestors. Some of that variability is due to environment, but some is also due to genetics – some people are better built for distance running than others, and no uniform training approach will work for all of these variants, nor will any single shoe. There is simply no longer a strong selection pressure to be a fine-tuned runner. As one example, I can train as hard as a want, but I’ll never run a 2:10 marathon – my physiology is simply not capable of doing it (and to be honest, I think running 26.2 as fast as possible is not something our ancestors did very often either). Some people have high arches, some have flat feet, some have unusual bone structure – these are all important when it comes to running ability, and some of them may be genetic.

3. You are correct that the dog example is not perfect, but it’s more appropriate than the cheetahs. What I was trying to do was find a parallel where we have a highly variable modern population descended from a less variable population of excellent runners. Humans and dogs got to where we are in very different ways (dogs have been artificially selected by humans), but I think the analogy holds. I teach developmental biology, and what’s interesting is that we are at the point where we can artificially select our own childrens’ traits right now – through IVF with prenatal genetic diagnosis we can choose their gender and select against an array of genetic diseases. Scary what could come next.

Thanks for the thought provoking questions.

Pete

About the new barefoot runners and injuries. Let me introduce an insurance term, “adverse selection”. In other words, the new barefoot runners are not a random sample of runners. They are likely disproportionately coming to barefoot running because of past injuries.

A good study would be to take shod runners and put half in bare feet and keep the others in their shoes and see how they hold up.

One more point. Chris McDouggal, the author or Born to Run and other evangelicals present barefoot running as the magic bullet for all homo sapiens. That had to debunked and Fitzgerald’s article is good as far as that goes.

Though I love running and I would be delighted if the world could somehow be explained by my favourite sport, I am inclined to agree with the Fitzgerald, that not all humans are born to run.

That is, although the availability of distance running capabilities in the gene pool may have been advantageous in earlier days, I don’t think that every individual had to be a great distance runner, nor that every individual had to run great distances every single day. I can hardly imagine a whole family group of prehistoric humans men, women, children, running down prey every day of the week. Yet, that is what the more evangelical ‘born to run’ proponents claim: everybody is a great distance runner and running marathons barefoot almost every day of the week is natural, because everybody did it in the Pleistocene.

Some of the literature Lieberman himself adduces in “” The evolution of marathon running” rather suggests the following picture:

The Hazda in East Africa forage daily for anything eatable at a distance of hour one hour from their camp at a water resource. They seize every opportunity to scavenge a carcass, when they encounter one. About 14% of their meat diet is scavenged, the rest is hunted. On average, a Hazda has 25g of scavenged meat a day, though availability is subject to large seasonal variation. A group of 45 to 75 individuals scavenged 11 carcasses in 14 months. They often run to a newly discovered carccass, but scavenge it not by outrunning other scavengers, but by chasing a predator or other scavengers away from a carcass, sometimes killing them.

(Source: link to clas.ufl.edu…

If this example is anything to go by, there appears to have been no single, overwhleming evolutionary pressure on every individual to become a great distance runner. It may have been advantageous, but so were other strategies, some of which may actually interfere distance running capabilities (for example: storing more fat than your peers). It rather suggests that the availability of some distance running capabilities in the population is useful, and perhaps even that some aptness in every individual is advantageous, but, given that, scavenged meat is only a small portion of the diet even if every opportunity is taken, and that large game, whether scavenged or hunted, is not the only source op proteins, it would not have been necessary for every individual to be a top distance runner. Nor is everyone running all the time.

Most are foraging daily, i.e. walking a couple of hours every day, so rather the ability to walk would be vital for everyone.

It appears that people are born to walk during their lunch break.

Thanks for the comment – I appreciate your thoughts. The point that

Lieberman and others are making is not that every single human is going to

be the next champion marathoner, but rather that we possess a number of

adaptations in our bodies that could be best explained as having been

selected for due to their role in distance running. Many of these have no

relation to our ability to walk. So, the logic goes, if we have running

specific adaptations, how did they get there? Because there was selection

for them at some point in our evolutionary history.

I’m not arguing that every modern human is going to be a natural born

runner, but rather that the mark of our running ancestry is still very

present in our bodies. Selection for running prowess has been removed for

quite a long time, and human populations are larger and likely a lot more

variable than they were 200,000 years ago. Even back then it was not

necessary that every individual be a champion runner, but those individuals

that were able to hunt effectively and provide for their families would have

been more likely to reproduce.

Pete

Perhaps I should have read your post more carefully before launching my crusade. Let me explain my point or, if you like, hammer some more on the same nail.

I do agree with you that the human capacity for endurance running is remarkable and may have an evolutionary explanation. Though at this moment I am not convinced, because I don’t think the adaptations Lieberman cites are solely explainable or even best explained by selection for distance running. Too much rests on the assumption that the anatomical traits he cites are solely useful in distance running.

Take for example the gluteus maximus, the large butt muscle. According to Lieberman this muscle is not of much use in walking, but essential in running. Most people nowadays don’t run. Most people do walk. Yet, most people still have a big size gluteus comapred to other primates. Why doesn’t this muscle atrophy, if most people don’t use it. One explanation would be that we’re programmed by evolution to support a big gluteus anyway. That would make this particular muscle a special case among other muscles that are essential for running, but do atrophy. The other explanation would be, that the gluteus is useful enough in upright walking. As far as I know the gluteus does atrophy in people who do not walk (or run), for example after prolonged hospitalization.

The same argumentation would apply to the calf muscle and Achilles tendon. The evidence Lieberman cites that the leg tendons are hardly used in walking seems to be based on a simplified model of walking, in which we don’t have knees or feet and sort of straddle on two rigid stilts. This model may be perfectly adequate for showing how much energy will be saved by adding a spring to our stilts in in running and thus show the advantage of elastic tendons in running. In this specific model, adding springs to the stilts in walking doesn’t do much. Yet that doesn’t prove that elastic tendons are of no use in walking. This very limited model is simply not designed to show in any detail all the properties that are relevant for walking. Besides, jumping is another useful behaviour that exploits the elastic properties of the leg tendons.

As for our unique cooling system: In my country (the not so tropical Netherlands) there is a yearly four day walking event. People can choose between hiking 30, 40 and 50 KM a day. In 2006 two experienced hikers died of heat stoke and several were hospitalized. The temperature was a hot, but not extreme 32 Celsius (90 F). Every army in a warm environment suffers heat stroke casualties, not only as a result of running, but also on field training, marches and forced marches. The evidence is anecdotal, but it seems to me that the cooling system of a fit, young, healthy person can be strained to the max by simply walking in the heat and by a range of other activities.

The possible relation of a slender waist to walking is less clear but the relation to distance running doesn’t seem all that exclusive. The free movement of the head has many other advantages. Many shock absorption features may be explained as adaptations to either the impact or the wear and tear of walking long distances. Human walking is pretty bumpy and walking on two legs instead of four doubles the impact of any movement.

The other difficulty I have with the distance running theory is, that it remains unclear what environment or lifestyle would have forced distance running upon us. To say there must have been some environment that selected us for it, simply because we’re remarkable at it, and adducing as evidence for selection the very traits that make us remarkable, is begging the question. Only an accurate description of the environment that selected us and evidence that this behavior and environment actually occurs or occured, can lend credibility to such a claim. Remember the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis?.

Take another thing we are exeptionally good at: throwing stuff. A basaball pitcher is unlike anything in the animal world in terms of both range and accuracy. The short forearms, the decoupled head, the slender, independently rotating waist all seem to fine tune us for throwing stuff. It is is tempting to suggest that we were selected for throwing things, because one can easily imagine a world in which people trew rocks at prey. Yet, how about our unique ability to do rougly the same with our feet? A soccer player can kick a ball pretty far and pretty accurately on the head of an oncomming teammate, even while running. Pointing to the very same anatomical features, we seem fine tuned for it. But what sort of environment would have selected us for playing soccer?

I am not saying that the ‘born to run’ hypothesis is wrong, but a strong theory requires strong evidence. On the basis of the evidence I’ ve seen so far, I don’t discount the piggyback hypothesis. In today’s world examples of traditional lifestyles that incorporate an large ammount of distance running are very rare, while walking lifestyles are relatively abundant. There is as yet no evidence that this was diffirent in prehistoric times. The soccer example suggests that piggybacking isn’t all that rare.

I hope I am not getting too fanatical. I should reserve that for my 10K.

You make some good points here, and the reality is that because we are

making hypotheses about things that occurred long ago, we may never

know the true answer. I look at the evidence and see a species that is

well adapted for both walking and running, and we possess traits that

make us good at both. There are some that overlap, and some, it seems,

that do not. It’s certainly very interesting to think about.

Couple of points:

1. The gluteus maximus is not inactive during walking, it is just a

lot less active than it is during running. It is also used in other

behaviors, like climbing and getting up from a squat or chair. Even

low level activity during other activity would probably prevent

atrophy even in relatively inactive people. That being said, it is

heavily involved during running, and differs markedly in it’s anatomy

from that in the chimpanzee.

2. You can always find exceptions to any rule. Sure, people die of

heat exhaustion. Humans are also highly intelligent and generally

logical compared to other animals, but we often die or injure

ourselves by doing stupid and/or illogical things (hence why we have

the Darwin Awards!). I doubt anyone would argue that we are far better

at thermoregulating than most other animals out there, just as few

would argue that we are intelligent. Running with my dog reinforces

this belief every time I take him out.

3. The hunting/scavenging hypothesis provides the selective

environment. We know roughly when our ancestors started eating meat,

and it was before we had weapons to kill from a distance. Running them

down is one hypothesis for how this could be done (emphasis on

hypothesis). Few modern tribes do this because they longer need to,

but the fact that some do is evidence that it can and has been done.

4. Your soccer kick example is interesting, but I view that as a

complex, learned behavior. I can’t kick a soccer ball with any degree

of accuracy, and my kids are even worse. However, you go to any

playground and watch kids and you quickly realize that walking and

running are both innate. Almost as soon as a human can stand, they

begin doing both (I say this while holding my 4 month old who is

desperately trying to use his legs to stand!).

I appreciate the discussion – thanks for your detailed response.

Pete

Thanks for taking the time to respond, especially since I am trespassing on your field of expertise.

I think you very rightfully emphasize that it is a hypothesis: A reasoned account of how certain observable traits may be explained from a past environment that is thinkable, but of which no real evidence has been found (yet?). . If, as you say, meat eating occured before the use of long distance weapons, that is indeed something that cries out for an explanation and would be explainable by this hypoyhesis. We can only hope that the fossil record is complete enough for an answer.

I agree with you that walking and running comes naturally to children. Playing with my brother´s children suggests they have a great capacity for repeated short bouts of speed, rather than for distances. As adults, they probably keep on walking but stop running. So the question remains, if distance running comes naturally. Like soccer, many human activities are highly trainable. I am probably worse at throwing a ball than you are at soccer, but I know that I could learn to throw properly. It is hard to say if I was born with the ability to throw properly, but lost it or if it is simply one of the unexpected things humans can train themselves to do, like walking on your hands. It could be the same for distance running.

Here is something intersting on the Achilles and plantar tendon in walking.

link to sciencedaily.com…

If the science behind it is correct, you’d spend 23% more energy with the Achilles and plantar tendon missing in one leg, so it saves about 19% of energy. I don’t know if you can simply add up for two legs, but even at 19% it seems like a pretty useful adaptation for walking.

Have you seen this video: link to youtube.com…. I

think kid style running is probably what our ancestors most likely did on

hunts based on what I see in the persistence hunt. Run for a bit, walk and

track, run a bit more. I suspect our ancestors were rarely running 26.2

miles full out. Unfortunately, we’ll probably never know for sure just what

the case is.

Throwing is definitely a learned behavior if my kids are any indication.

Funny how kids in the US probably learn to throw a ball first, whereas kids

in Europe probably learn to kick a ball first. Sport is a big influence!

Pete

Great!

Did you notice that he’s a heel striker with his right foot and a forefoot striker with his left? (3.13 min)

Yes, I saw that. Have also seen a few people in race videos doing that. Very

interesting!

Pete

They were wearing shoes. So the fact that they were heel striking is not very surprising.