Contrary to what you may read in the coming days about a new study that just came out, Vibram just got the best Christmas present they could have received.

Contrary to what you may read in the coming days about a new study that just came out, Vibram just got the best Christmas present they could have received.

The question of whether minimalist running shoes reduce or increase injury risk has been debated extensively over the past 3-4 years. Much of this debate has been based largely on anecdotal reports from runners and therapists: many runners have reported resolution of long-term injuries by moving into more minimal shoes, and many therapists claim that they have seen upticks in the number of patients reporting injuries resulting from moving to more minimal footwear.

I believe that anecdotes can provide valuable information, and in this case I do believe that individuals making these claims are speaking the truth. I believe that people have overcome injury by going minimal, and I also believe that others have gotten injured as a result (I have seen both sides in my own client population). But, what we have largely lacked to date are published studies investigating injury risk associated with footwear along the spectrum from maximal to minimal.

One such study was just published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, and at first look it might seem to shoot down the claims of minimalist aficionados. The study, authored by Michael Ryan and colleagues, is titled “Examining injury risk and pain perception in runners using minimalist footwear.” I’m quite sure it will be the source of considerable debate, so I thought I’d give my take on the results.

Study Methods

The study employed a prospective, randomized controlled design (not blinded, tough to do that with shoes!), which gives it more weight than other injury studies that have been done to date on this topic (many of which are survey-based). The authors recruited participants with a minimum of 5 years of running experience to participate, and all had to be capable of tolerating a 20-40 km/week training load (in other words, these were experienced runners). A key point is that individuals who already use minimalist footwear were excluded. So, moving into minimal shoes was a change from the norm for those in the experimental groups. Thus, they were essentially studying transition injuries.

Ultimately 103 (99 completed the study) runners were randomized into one of 3 footwear groups: traditionally cushioned Nike Pegasus, mildly cushioned and highly flexible Nike Free 3.0v2, and minimally cushioned Vibram Fivefingers Bikila. Here’s how they describe the training program that each group followed:

“Following a 1-week break-in period to their assigned footwear, participants began a 12-week run training programme developed by the authors targeting a 10 km run held in Vancouver, British Columbia in November, 2011. The programme followed a gradual increase in total running minutes from 160 min the first week to a peak of 215 min in week 10 before a 2-week taper. Participants did not always run in their assigned footwear, rather had a gradual increase in exposure as a percentage of their total weekly running time starting at 10 min (19% of volume) in week 1 to 115 min (58%) in week 12. If a participant felt that repeated use of a shoe was significantly contributing to pain anywhere in the lower extremity, they were given the option of withdrawing from the study.

The programme incorporated three to four run workouts a week, with a longer group run on the weekend and interval training during the middle of the week. The 2–3-weekday workouts were based on time, while the long run on the weekend was based on distance, in order to accommodate different training paces but ensuring adequate preparation for the 10 km event…it was estimated that the weekly volume started at approximately 15 km and increased to 30–40 km at the peak of the programme.”

The study authors tracked injury events (an injury was an incident that caused 3 consecutive missed runs) and pain with running at several points during the 12-week duration of the experiment.

Study Results

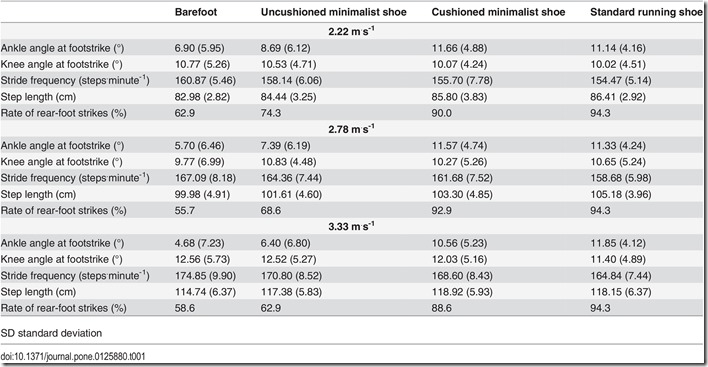

A total of 23 injuries were reported by the 99 runners over the 12-week training period (injury incidence = 23.2%). Injury results among groups were distributed as follows: 4/32 (13%) in the Nike Pegasus got injured, 12/32 (38%) in the Nike Free 3.0v2 got injured, 7/35 (20%) in the VFF Bikila group got injured. Injury risk was significantly higher in the Nike Free group compared to both the Vibram and Nike Pegasus groups. Risk of injury was not not significantly different between the Vibram and Nike Pegasus groups.

Results for pain during running were mostly non-significant, with only calf/shin pain in full minimalist runners being significantly higher.

Based on a statistical analysis of the results, the authors conclude “Based on injury event data, there is a higher likelihood of experiencing an injury with minimalist footwear, particularly with the partial minimalist condition.” (I disagree a bit with this phrasing since injury risk was not elevated in the Vibram group)

Commentary

1. The first point I’ll address is sample size. People are going to complain that sample sizes here are too small, particularly the number of people injured in each group. I’ll address this by saying that studies like this are time consuming, expensive, and not easy to carry out. So, we have to work with what we have. That being said, I do think the small samples prevented identification of some possible significant differences between groups (e.g., the Pegasus group was over 70% female, whereas the Free and VFF groups were closer to 50-50 male-female). Would the higher injury rate (20% vs. 13%) in the Vibram group have represented a significant difference if larger samples had been employed? Maybe, but we again have to work with the data in front of us. We use statistics for a reason, and the stats here say no difference in risk between the two groups.

For one example, if we wanted to ignore statistics and play the trend game with the data, we’d find that the Nike Free group had least pain in the shin/calf (is 4mm drop protective for the calf/shin vs. 12mm and 0mm???), but had the most pain in the knees (plausible case for lack of form change interacting with less cushion?). But, we can’t do this because the stats say the differences are not significant.

2. The injury rate in the Nike Free 3.0 group was indeed fairly high, and risk of injury was significantly higher than in the other two shoes. However, in the Kaplan-Meier plot (Figure 2 in the paper) as well as in the tables presented in the supplementary data, risk of injury in the Vibram Fivefingers was not significantly different from the Pegasus (for example, confidence interval for absolute risk reduction in VFF compared to Pegasus overlaps zero, confidence interval for relative risk in VFF relative to Pegasus overlaps 100% or 1 – statisticians, correct me if I’m wrong on my interpretation!).

So in reality, this study shows that transitioning to running in a full minimal shoe isn’t any more risky (or better) when it comes to injuries than continuing to run in a traditional shoe like the Pegasus. It’s moving to a cushioned but more minimal shoe like the Nike Free 3.0 that poses increased risk, and the authors suspect this may be due to the fact that the moderate amount of cushion in the Free isn’t enough to encourage form modification, and isn’t enough to protect runners who continue to run as they did in a heavily cushioned shoe like the Pegasus. Makes sense to me (and interesting personally since the Free 3.0 was my gateway-shoe to minimalism!).

3. The authors don’t talk much about pain, mainly because most differences observed were not significant (I think the sample-size effect comes into play here). The only significant difference observed was that runners in the full minimal Vibram Fivefingers reported greater pain in the calf/shin. My guess is that this was mostly calf pain (they don’t specify), as a period of initial calf pain is almost universally experienced by those transitioning into minimal shoes (myself included). The study authors explain this as follows:

“It is noteworthy that runners in full minimalist footwear condition reported greater calf and shin pain throughout the 12-week period. This finding was not unexpected given the likelihood that some of the runners in the full minimalist footwear condition adopted a forefoot strike pattern that could have resulted in greater (and unaccustomed) loading of the Achilles tendon and triceps surae musculature secondary to a larger ankle dorsiflexion moment immediately following touchdown. The greater heel height in the partial minimalist footwear likely mitigated this loading on the shank.”

I had bad calf pain when I started running in VFFs back in 2009. It was transient delayed onset muscle soreness that diminished and eventually went away after I adapted to running in the shoes (much as starting to lift at a gym can cause bad muscle pain for a period of time). It would be helpful to know if this calf pain was muscle soreness or something else, but I suspect this is something that would lessen over time.

4. I dread seeing headlines touting this study as the nail in the coffin for minimalism. You could just as easily turn it around and say that this study supports the notion that wearing a highly cushioned shoe provides no injury protective benefit over a shoe with virtually no cushion at all.

I also reject the notion that a study like this can say much about any entire class of shoes. The Nike Free 3.0 fared poorly, I don’t doubt the data. Though it is a personal favorite shoe, the Free 3.0 is fairly narrow, extremely flexible, and does not provide a lot of medial support (I moved my wife out of them because she tended to cave in the medial side of the sole). Is the Free 3.0 representative of all minimal shoes? Not at all. Just as I would not say the Pegasus is representative of all traditional shoes, or the Vibrams are representative of all fully minimal shoes (I get forefoot pain in Vibrams for example, but not in other ultraminimal shoes – something to do with the toe pockets I think).

If anything, this study shoots down claims that:

a) Minimal shoes are a panacea for running injuries. They aren’t. They can cause injuries for some, and for others they might just be the solution to a long-term injury. We’re all different, and it’s all about what works best on an individual level.

b) Barefoot-style shoes are too risky and running in them will get you injured. The results here actually suggest that transitioning into barefoot-style shoes is not as risky as some suggest (particularly those with an anti-minimal bias). I’d add the caveat that the transition should be gradual, much like the one employed in this study. But runners who transitioned from traditional shoes to Vibrams in this study were at no greater risk of suffering an injury than individuals who continued to run in a more traditional-style shoe. This is why I consider this study a Christmas present or Vibram – it gives them a prospective study in a high profile journal to cite that shows that their shoes are not any more likely to cause an injury than more typical running footwear. In fact, they are apparently safer than the Nike Free, which is one of the top selling shoes in the United States!

Update 12/25: I forgot about it when I first wrote this post, but I should point out with regard to the above statements that this is now the second study to find no difference in injury risk between minimalist shoe wearers and those in traditional shoes – I wrote about the other here (based on an abstract from the ACSM meeting).

5. It’s worth emphasizing again that this was a transition study. The Nike Free and Vibrams were novel conditions for all of these runners, and the Pegasus was presumably more similar to what they were used to. So, the study can only really assess injury risk when transitioning into minimal shoes. We really need longer term studies of how people fare in different shoes, and studies looking at how different shoes might be used to help with (or if they are contraindicated for) specific injury types (this study did not break down injury types as diagnoses were not available). For example, I’d love to see a study on whether moving to a Vibram-style shoe helps with knee pain, or whether wearing a Hoka style shoe helps with foot pain. We need to confirm or refute the anecdotes in cases like these.

At the end of the day, what I think this study shows once again is that there are myriad options out there to choose from, and no one end of the shoe spectrum is inherently better or worse than any other. These results would not stop me from recommending a minimal shoe where I think it’s warranted, and they don’t support claims that minimal shoes are a cure-all. I sent a client home yesterday with the suggestion that he try a pair of Hokas, I myself prefer more minimal stuff. Different strokes for different folks, embrace variety and find what works for you.

For more on this study, view articles by Blaise Dubois and Craig Payne.

Another great, spot-on piece, Pete! Thanks for your review of this study. Cheers!

Thanks Paul!

While I’m no expert in the field, what this confirms to me is that different styles work well for different people. Yes, I do think that minimalist shoes help people learn better running form, but I’m never going to say that minimalist, maximalist, stability, motion control, or whatever shoe is the ONLY type of shoe that people should run in. I enjoy my Skechers Go Run 2’s (Nike Free-ish), and I feel better running in them than I ever did with a stability shoe.

Well said!

It’s kind of funny how this turned into a war between the forces of minimalism and the cushioned team. I’ve found that I can start to have problems in either type of footwear. It’s my focus on form, and what I think works, that has helped me nip problems in the bud. It’s fun to try different shoes and maybe wearing many different types helps keep injury at bay. However, I think that ultimately, the shoes don’t really matter much. Some people say you should just stick with your natural form, but I’ve found that trying different things (and that can mean copying elites and runners who people think of as “natural talents”) has helped me run better than I thought I could and stay injury-free as well.

I agree. It’s kind of silly to take a black and white approach. We’re all a bit different and the goal is to find what works for you with regard to both form and footwear.

Not surprisingly, I’d like to see a study like this that includes barefoot and/or huaraches (preferably Xero Shoes ;-) ).

My contention (and personal experience) is that even the Bikila doesn’t give enough sensory feedback from the ground (ironically, that shoe was the first made by Vibram specifically for running, and is thicker than the previous models). And the secondary contention is that additional feedback would be useful for the transition.

Now, the next question I wonder is: what changed, if anything, in the gaits of the people in this study?

Yes (anecdotally!!) I think that’s probably the reason. The proprioceptive feedback I get when I run truly barefoot on grass is immense, and my calves (my, ahem, “achilles heel”) are relaxed and almost fresh after a barefoot run, perhaps at least partly by the incredible variation of stresses occasioned by the micro-changes in form induced by an irregular surface such as grass –The Vibram Five fingers are a distant second best in that regard, btw.

Take away that feedback, however, and put me on a uniform surface such as pavement in, say, the adidas adipure gazelle, and my calves scream bloody murder afterwards, and I need for some reason to have a decent stack height to remove the strain caused by the lack of feedback + the pounding that the pavement and my form conspire to create.

So for me, on hard surfaces, a traditional racing shoe or trainer-racer seems to work best. The now-discontinued Adidas Mana were my holy grail, and I really like the adios 2s, but they get very hard in the winter.

WD I think you have hit the nail on the head. I have always thought we were not born to run barefoot or near barefoot on pavement with no feedback but we were born to run barefoot on grass, hard sand, dirt.

It’s regrettable that you use the term “born to run.” That is one phrase I would like to see disappear in 2014…

I still like that phrase. It was that book that started me thinking that there had to be a better way. I know everyone seems to like to move onto something new and cool, and forget anything old, but that book is still good, even if it is a few years old now. I’ve had to accept the move away from barefoot/minimalism recently, because few people had the patience to get it, but I’m still a true believer. I see the same big old trainers and even Hokas in 5ks, but until I see elites wearing Hokas in the 5000 and 10000 m, I’ll stick with flats and minimal shoes most of the time. Even if no one is exactly “born to run” it sure can feel like you were if it’s fun and doesn’t hurt.

I agree, this blog wouldn’t be what it has become if Chris had not written that book. I still like the phrase.

Looks to me that the pegasus Group, really should try a different type of shoe. Maybe a lighter shoe with less drop and cushion? :-)

Actually it shows that neither group is better than the other, which to me supports trying something different if you are not having success (on either end of the spectrum).

Yes, I would actually say the pegasus Group differs from the other groups. They run in what they should be used to and are not transitioning. So why do they get hurt?

Ramp up in training mileage in preparation for a race would be my guess.

Great insight as usual, Pete.

I agree that this is a study examining the effects of transitioning to a different shoe. If they did a study on runners who traditionally wore lightweight flexible shoes and transitioned some of them to the Brooks Beast, I’d imagine injury rates would be higher in that group.

My point is that soft tissue and bone need to adapt to the loads you place on them. If you introduce a different load, your risk of injury may go up due to tissue adaptation not keeping up with the altered load.

In this study, the Pegasus group didn’t have an appreciable change in load that they had to overcome.

Still, I applaud the authors for adding to the knowledge base, and I very much appreciate your analysis of it.

Kevin –

I think the most surprising thing to me is the lack of a significant increase in injury risk in Vibrams over the Pegasus especially since this was a transition study.

Pete

I agree.

My initial thought of why this was is because in ‘partially’ minimalist shoes, load changes but form doesn’t change that much. Whereas in ‘fully’ minimalist shoes, form tends to undergo change to adapt to the load (not always, but usually). We really don’t know thought.

These are questions that have very complicated answers, however I think we are all being wildly simplistic to think that shoes have a direct, linear relationship to injuries.

In the end, injuries are very subject specific and multifactorial.

Basically, there is a chance you will get injured in ANY shoe.

I have run in:

New Balance 730 V2

Nike Free 5.0+

Nike Pegasus 30+ Shield

Nike Alvord

Mizuno Wave Rider 16

Saucony Triumph 10

The only injuries I ever seem to have are the occasional sore soleus after really hard tempo runs of more than 6-7 miles and the occasional knee twinge that seemed to start when I started using the Mizuno Wave Riders. What does this mean? I have no idea, but thought I would post it…

Looking at my personal experience, I cannot help but question the validity of such studies where they give minimalist shoes to new runners and expect them to transition automatically to a whole different running experience.

In my case, before I was able to run rough technical trails in VFF or Luna Sandals or others, it took me a whole year of transition, during which strange things happened in my feet muscles, tendons etc.

Mario

But the surprising thing here is that the Vibram group did not experience an increased injury risk even though this was a transition from a traditional to a very minimal shoe.

“it was estimated that the weekly volume started at approximately 15 km and increased to 30–40 km at the peak of the programme.”

so we’re talking 9ish miles to start and getting up to about 25 on their hardest week. Not to be a distance queen, but that’s not a lot.

“Participants did not always run in their assigned footwear, rather had a gradual increase in exposure as a percentage of their total weekly running time starting at 10 min (19% of volume) in week 1 to 115 min (58%) in week 12.”

On that 25 mile week, 12 weeks into the program, they wore their assigned shoes for just under 2 hours. Again, not exactly a ton.

Would these injury rates remain the same as the mileage ramped up? Or if they 100% transitioned to a different type of footwear?

Good questions, this study was not designed to address them. What it shows is that a gradual buildup in training in Nike Free increases injury risk, whereas risk with a gradual buildup is not increased in Vibram Fivefingers. The authors openly admit the limitations with regard to longer term trends.

I would like to see a study using other brands of shoes that tries to see an average across several brands of cushioned, minimalist and in-between shoes. That way you can make assessments of type of shoe rather than specific models.

It is possible that the Nike Frees are just bad shoes and so they had a higher injury rate.

I had a pair of Nike Free and the shape of the shoe seemed to make it difficult for me to run either with landing on my heel or on the front of my foot. It may be because I have relatively flat feet but it seemed there was too much cushion on the arch and so all the impact from each step was focused there. It eventually caused a foot injury and ended switching to a more minimalist shoe and haven’t had any problems since.

I agree, but it would be very difficult to get a big enough sample and such a study would be very expensive.

Peter,

Another quality post. I forgot to comment on this back when you first published it! Another piece of evidence that its not so much about the shoe thats on the foot as it is the foot in the shoe. By foot I am implicating the entire body…neuromuscularskeletal…circulatory…psychosocial…Each person’s formula and composition is unique and contribute in a novel fashion to each specific injury.

Excellent review! I’ve gone the minimalist route and never had a problem, but I hate the look of the Vibram FiveFingers!

Hi Pete,

Havent read the study yet, have been away, but I think there is an interesting aspect here with the amount of previous experience in each type of shoe. Considering that the move to minimalism was a novel one for these subjects, we can make the assumption that the majority of these subjects who were injured in the different shoes were injured due to CHANGE. That is of-course an assumption, but it would appear to make sense. For the pegasus group however, this shoe condition could be considered the “norm” (despite possible small changes in shoe design), and any injuries in this group cannot be associated with such a large change, but instead to other factors. Considering this was the condition that so closely resembled their previous 5 years of running experience, it seems to be a very high injury rate that is hard to just explain due to the race preparation – I look forward to reading the paper.

Good points. I was really pretty surprised by how well the Vibram group did in comparison especially since it was a major change from their norm.

Great study! It would be interesting to quantify the data by age group and injury history etc.