Image by SashaW via Flickr

In my previous post I summarized a slice of what was covered at a three-day course called “New Trends in the Prevention of Running Injuries” that I attended last weekend in West Virginia. In addition to discussing what we do and do not know about the causes of running injuries, the course instructor, Blaise Dubois, a Canadian physiotherapist from Quebec City (Blaise is on the far right in the image below), went in depth into some of his treatment strategies. Blaise feels very strongly that big, bulky modern running shoes are not helpful to runners, and he indicated that he has been prescribing racing flats to his patients for approximately 8 years with good success. In addition to shoe changes, Blaise is also an advocate for natural running form, and he feels that the form that high-heeled, heavily cushioned shoes allows is potentially a cause of injury in some (many?) runners.

So what exactly is natural running form? Basically, natural running form is the form you would adopt if you regularly ran barefoot. Blaise, however, is a realist, and being from Quebec City where it is ridiculously cold and snowy in winter, he realizes that running barefoot is not going to fly with most of his patients. As such, rather than focusing on minute details of form, or advising patients to focus on their footstrike or other aspects of biomechanics, he instead focuses initially on cadence (check out Blaise’s 10 Golden Rules here). In addition to flatter shoes, he will generally recommend that patients aim for a stride rate of 170-190 steps per minute, and he finds that this will often be enough for a runner to make a noticeable change in form.

If working on cadence alone doesn’t achieve the desired result, he adds in other cues such as telling the patient to “make less noise” when they run, or he tells them to “run softly.” Generally, if you’ are pounding the treadmill or ground when you run, it might not be the best thing for your feet and legs. Blaise also does not seem to obsess too much about footstrike – if cadence and form look overall good, a mild “proprioreceptive” heel strike is not a big deal for him (Jay Dicharry from the UVA Speed lab echoed this – he indicated that footstrike is highly variable and not always perfectly correlated with things like impact force). A ground pounding overstride, on the other hand, is a different story – not all heel strikes are created equal.

Blaise indicated that in his clinical experience, making a shoe change (I love the fact that he prescribes racing flats!), working on increasing cadence, and coaching his patients to run quietly can have often have very positive benefits in terms of helping them overcome chronic injuries. During the course Blaise demonstrated his technique for coaching cadence on several participants – it was pretty amazing to watch. After observing the runner while running at a comfortable pace on a treadmill, he first looks for any obvious biomechanical flaws. Next, he determines their stride rate, and if it is low (say around 150-160), he makes use of a digital metronome to help guide patients to a faster stride rate of around 180 steps/min (you can also download an iPhone app that acts as a stride rate metronome). It feels awkward at first (and I can vouch for this as moving to a midfoot strike felt awkward to me for a long time), but with GRADUAL and PROGRESSIVE practice the new gait is learned and the motor patterns become ingrained (I’ll be writing more about this soon). The hope is that the gait change resolves the repetitive stress issue that caused the injury that landed the patient in Blaise’s clinic.

One often hears the magic number of 180 strides per minute thrown around these days as being the optimal cadence for a runner, and it is the number that Blaise generally recommends. I believe this number can be traced back to famed coach Dr. Jack Daniels observation that elite runners tend to run at a stride rate of 180-200 steps/minute. I’m not sure that we have any conclusive data saying that the 180 number is optimal for every person, but Heiderscheit et al. 2011 showed that running with a faster cadence/higher stride rate (5-10% increase) reduced loading on the knee and hip, allowed for a more level carriage of the center of mass (less vertical oscillation), shortened stride length, and created less braking impulse (read my post on the Heiderscheit paper here). All seem like reasonably positive outcomes if you ask me, and this paper might be a useful guide in that a mere 5% increase in you cadence might be all that is necessary to realize some benefit. It turns out that the 170-190 range would probably be where most people would land if they increased cadence by 5-10%.

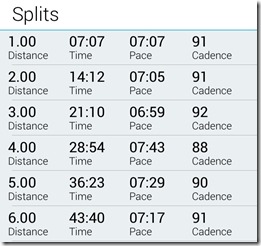

To determine where I fall out, on my run today I wore a Wahoo fitness footpod that syncs via an ANT+ sensor (Wahoo Fisica) plugged into my iPhone and gives real-time cadence output. What I found was that my cadence hovered between 182-185 steps per minute for most of the run (pace ranging between 7:30-9:00 min/mile – lots of snow mucked up my ability to run steadily), but on two occasions when I surged to about a 6:30-6:45 min/mile pace, my cadence rose to around 200 steps/min. I wish I had cadence measurements from before I embarked on changing my gait, but I feel quite certain that one of the biggest changes I have made is adopting a shorter, quicker stride, and at this point it is more or less ingrained and feels completely natural to me.

I should point out before I wrap up this post that the approach of gait retraining as a treatment protocol for broken runners is not a new one in the world of physical therapy. Blaise has been doing this for many years, and Matt Fitzgerald actually wrote an article about gait retraining for Runner’s World back in 2004. As Fitzgerald points out in the article, there has always been some amount of debate about whether running form is too ingrained to be changed. However, recent scientific articles (e.g., this one by Crowell and Davis, 2011), suggest that form change via gait retraining is indeed possible, and that it can stick even after a patient leaves the clinic. My personal experience working on my own form would support this – I run very differently now than I did early in 2010. Is it better? I don’t really know, I just know that it’s different.

It’s also worth emphasizing that not everyone needs to pursue form change, or even a change in shoes for that matter. There seemed to be a general consensus among people in the course last weekend that if a runner is running well and has not had injury problems, it’s best to just leave things alone (I clearly didn’t get that message…). In Matt Fitzgerald’s article he quotes Dr. Irene Davis, one of the leading physical therapists working on gait retraining for the treatment of running injuries, who stated “If you try to ‘fix’ your stride when you’re uninjured,” says Davis, “it’s more likely that you’ll cause an injury than prevent one.” Caution is warranted, and consulting a physical therapist who has experience with gait retraining is a good idea if you are injured and apprehensive about doing it on your own. I plan to write a post summarizing a few of Dr. Davis’ recent papers in the coming weeks – some very interesting stuff!

For more on gait retraining, here’s another interesting article by Matt Fitzgerald, this one on Competitor.com.

Pete – I guess I didn’t get the memo either ;-) I’ve been successful over recent months in increasing my cadence, which has reduced my stride length, and by doing so has given me a good mid-foot landing.

Nevertheless, at Newton’s Natural Running Clinic recently Ian Adamson found numerous other running form abnormalities and loss of efficiency. This recognition prompted me last week to hire an excellent sports biomechanist with Memorial Hermann’s Sports Medicine Institute as they are quite experienced in reforming abnormal and potentially injurious running gaits, especially those resulting (as in my case) from correctable muscular weakness. My blog post on this topic is at: link to runinamerica.com…

Mark – just read your post earlier today – good stuff! Do they also

recommend 180 and getting away from bulky shoes at the place you had your

analysis done?

Pete

Pete,

I just want to thank you for creating/managing this blog. I have club runner friends who are curious about my running gait. I, too, have experimented in the minimalist/natural movement with great results. Often, I cannot find the correct words to describe my experience, but your blog echoes my thoughts.

I’ll be recommending runblogger to anyone willing to change.

-Jules from dailymile

I posted on my blog about an article not too long ago that I read reporting a study in which the data indicated gate retraining improved symptoms in runners that experience patellofemoral pain. I’m going to read all the posts based on your experiences at the conferences with great interest and geek out over the science and mechanics of it, I think. My wife will find my foaming at the mouth at the computer.

Sorry Pete, I really love your blog and your insights, but your latest posts suggest that you and the other guys who NOW care about a cadence around 180, using a metronome, lifting their feet off the ground and running barefoot or with minimalistic footwear would have invented the wheel. This stuff is out there for more than a decade! Have a look at Hal Higdon, Gordon Pirie, Jack Heggie and have a look at Posetech (which is around since 1997 – also a clever copyist) and all talk about the same stuff for ten years or more! Even in Germany we have sports science articles out in 2008 regarding the disadvantages of modern running shoes. IT IS NOTHING NEW! I find it rather amusing that almost every year emerges another clever copyist, who claims to have invented the one and only running style (or technique). We have our own share of them in Germany as well. It is ok to make money. But it is not ok to deny the sources. This is IMO pathetic.

Who is denying the sources? Blaise had probably the best cited and

researched presentation on form training i have ever seen – he cites

everyone. In fact, if you read the second to last paragraph of my post

I point out that this is not new. What’s new is that it is becoming a

more accepted practice in the medical community and there is now more

and more science coming out to back it up. Edward Munson pointed out

the problems with shoes back in 1912 – I posted a picture from his

book in my previous post. He predates Pirie by decades, and yes, I

have read Gordon Pirie’s book. Danny Dreyer from Chi Running was at

the course, and like Romanov he has been doing this for a long time.

Nobody is claiming to have invented this form. It is the form we

likely had run with for 2 million years prior to the advent of modern

running shoes. We are simply interested in spreading word to the

greater running community that perhaps the form our shoes allow us to

use is not the one that is best for our bodies. To be honest, the

thing that really stood out to me at the course was the lack of

financial motive behind many of the people promoting natural running –

there is a genuine interest to help runners avoid getting hurt, and

claiming to have reinvented the wheel is not what this is about.

Everypne has to make a living, and i begrudge nobody of that, but in

the end we’re all in it together.

Pete

Hey Pete – I’ve been enjoying your blogs on the WV clinic and am looking forward to your continued summaries.

As to your reply to Exu-rei…

I appreciate folks like you and others who are helping to inform the running community on ideas of ways to possibly prevent injuries so we can continue to participate in an activity/sport we love. And I think you said it perfectly with the following:

“In the end we’re all in it together.”

Sharing of first hand information (as you have been going through modifications to your own form and testing various minimalist shoes) has really been of value to someone like me who has been doing the same thing. It is both encouraging and enlightening and gives me ideas on how to improve my own running, but more importantly – to help the athletes who I have the privilege of coaching.

Thanks – and keep up the great work.

Thanks – I do my best, and I always recognize that there are a lot of others

who have been saying this stuff a lot longer than I have. However, just as

we have professors at every college in the country teaching anatomy (I am

but one), we need as many voices as possible teaching about running form if

we are to spread the word that there are other ways to go about things. I

didn’t invent anatomy, and I didn’t invent form change, but I enjoy writing

and teaching about both. Appreciate your reply!

Pete

Pete, I managed to scrounge up the text on the Crowell / Davis article:

link to sciencedirect.com…

Thanks Kent – I have the PDF, but did not know it was available free

online. Appreciate your scrounging work! Curious, do you use gait

retraining like this in your clinic?

Pete

Yes, we do, but not as formally as I’d like. The goal (the practice that I work for is moving me to another facility a few miles away in the next few months) is to expand the on-site form-training. We’re tinkering around with a few ideas. I’d really like to go with some sort of accelerometer monitoring because I think that it’s the better way to go. I have the ability now to use Dartfish to do “in the action” monitoring but that would tie up the computer that I use for many other things. For now, I rely on a great deal of verbal awareness cueing while my runners on on the treadmill as well as some barefoot treadmill work and a great deal of coaching on adding soft landing form modifications to the 2nd mile of training runs. In-house, I’m aided by the fact that I have a treadmill with a loose bracket under the deck – when one runs with a too-heavy footstrike, it causes the bracket to rattle – I cue my runners to run softly enough to prevent the rattle. Sounds a bit crude, but it actually works quite well.

Great post Pete. I recently began to focus on running quieter/softer. This was in on top of the recent addition of barefoot cool-downs after my trail runs. Is it normal to experience more calf soreness than usual when making this transition?

Keep up the good work!

Yes, calf soreness is very common in transition. It usually improves with time, but sometimes can linger if you are really tight in the calf/Achilles tendon. Just be careful and don’t push too hard when sore. Wearing a lifted heel to give it a break during transition can help as well.

Pete

Sent from my iPad

I “forced” myself to change my foot strike towards the end of this past summer and now I have a hard time if I try to heel strike on purpose- it just feels awkward. I’m not sure about my strides per minute, but I’m going to download a metronome for my iphone to see if I can make an estimate. Thanks for sharing more thoughts from the WV clinic!

Funny how what feels normal changes, isn’t it! The iPhone metronome app I linked to in the post is free. You could also just count your footfalls for 15 seconds and extrapolate.

Pete

Been working on the cadence for several months now and I must say it is difficult. Shortening my stride at 8min pace feels like shuffling. There must be a difference between the appropriate cadence for a 5 foot 4 inch marathon winner and 6 foot 4inch former small forward. My best attempts so far have yielded 168-170. I’ll check out the link to see if he has any other tips I haven’t tried yet.

I think accounting for body type mat be warranted – what is your baseline starting cadence, and how much higher is the 168-170. A 5% increase from baseline may be enough to see change without going all the way to 180, which is largely an arbitrary number that may not apply to everyone.

Sent from my iPod

Very interesting and useful post Pete. I have been playing the adidas miCoach pacer the past few days using the stride sensor in conjunction with the GPS phone app. I am finding that my stride rate seems to directly correlate to my pace. 8:30 or so pace is 173 strides/min for me. Yesterday as I slowed at the end of my long run into 10:00 pace I was down to 168 or so. What surprises me is the very slight % wise difference in stride rate when compared to drop in pace. My pace slipped 17% while my stride rate only slipped 4%. This would seem to indicate that keeping stride rate up even a tick or two per minute especially when tired would be key to maintaining pace.

I agree – and it may vary a bit from person to person. I was above 180 even

when running at close to a 9:00 pace, and didn’t really see things creep up

until I really increased pace to 6:45 or so. Didn’t sustain that pace for

long since it was icy, but would be interesting to see if it settled back

down after cruising a bit at a faster pace. I found myself between 180-190

for most of the 7:00 to 9:00 pace range.

Pete

The only problem with increasing cadence is that it is usually associated with a decrease in economy (Noakes. other sources). Recommending a shorter stride is great for overstriders and the chronically injured, but not for elite performance where stride length and cadence need to be optimized for efficiency.

I like the run soft rule. If you can’t hear your feet pounding, then chances are you are running in a way that will minimize your risk of injury.

One thing to be careful about with economy studies is that if they are not

long term, it is difficult to come to firm conclusions. It takes time to

adopt a new stride with any degree of efficiency, so measuring economy at

one cadence than asking a person to switch on the spot will almost always

result in reduced economy since it is a novel behavior that a runner is not

used to. Not sure if these studies have allowed for a proper level of

accommodation. That being said, I would agree that this is something elites

would have to be much more careful with, and they are not the group I would

target with a post like this. I’ll leave that to the coaches!

Pete

These are all sound improvements to running form, but you need to exercise caution in making them all at once. If you change your cadence, shoes, and way of impacting the ground you could be making too many changes, too quickly.

Another strategy to improving form is to sprint at maximum effort several times a week. This can reinforce proper running form very effectively.

Thanks for the analysis Pete! I checked my own stride rate and was right at 180 yesterday. Working for me.

Good points – care and caution should also be foremost in mind when any

change is made.

“I believe this number can be traced back to famed coach Dr. Jack Daniels observation that elite runners tend to run at a stride rate of 180-200 steps/minute.”

It’s older than that.

“All marching movements are executed in the cadence of Quick Time (120 steps per minute), except the 30-inch step, which may be executed in the cadence of 180 steps per minute on the command Double Time, MARCH.”

link to rdl.train.army.mil…

As you no doubt noticed in Munsons’ book, the form he observes for a double-time march is identical to what a modern minimalist runner is attempting, and the rate is the same as well. Munson doesn’t mention 180 ppm in his book, but it was the pace.

Is a double time march a run? I’m not all that familiar with the military

terminology. Doesn’t surprise me if Munson had it – he was obviously on the

ball with all of this stuff.

Pete

I’m curious who he’d recommend flats to for daily training.

Mostly everyone if I understood correctly.

Pete

On Wednesday, February 23, 2011, Disqus

That’s interesting. I’d like to ask him myself one of these days. Might have to try flats sometime. I used to race in them.