Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia “Overuse injuries of the musculoskeletal system generally occur when a structure is exposed to a large number of repetitive forces, each below the acute threshold of a structure, producing a combined fatigue effect over a period of time beyond the capabilities of the specific structure.” Hreljac et al. (2000)

The question of why runners get injured is one that I have been mulling a lot over the past year. Though I truly believe that most running injuries are ultimately due to training errors (some combination of running too far, too fast, and too often), I also suspect that running form and shoe choices can play an important role. Whether this role is outright or by exacerbating the effects of training errors largely remains to be answered. Let me state openly at the outset of this post that I don’t think that there is currently any convincing evidence showing any consistent causal relationship between running shod or unshod, on the forefoot, midfoot, or heel, and the likelihood of getting injured (there are suggestive relationships which I will touch on in coming posts, but few direct links that can be universally applied). I have seen people who run shod get injured, and I have seen people who run unshod get injured. I have heard from people who regain an ability to run injury free when they go barefoot or to a more minimal shoe, and I have seen people who have run shod for years who have not suffered any form of serious injury (I am in the latter group myself). Given the degree of human variability, we might never find a consistent pattern, but then again maybe we will – it’s hard to say. I suspect that some people are simply more injury prone than others, some people are better at recovering from minor wear and tear, and we all handle training loads differently.

What I would like to do in this post is provide an overview of the causes of repetitive overuse injury in runners, and to talk a bit about my approach to injury prevention and how it relates to my training strategies and my choice(s) of running shoes. Much of what I will write is highly speculative and likely not supported by a wealth of hard data, but I’d like to report my anecdotal experience in the hope that it will generate discussion and additional thinking on the topic (by both you and I). If you have anything to add or share, please feel free to do so in the comments – I’m very interested to hear more about different approaches to injury prevention. Here goes…

A few weeks ago I was listening to an episode of a podcast called Geeks in Running Shoes. In the episode the hosts, Jason and Raymond, both of whom are beginning runners, asked my friend Lam, who is a physician and writer of the Running Laminator blog, what his approach was to choosing a running shoe. Lam’s response was that he believes in running in several shoes of varying structural properties so as to expose his feet and legs to different stresses and forces on each run. Lam talked about how the feet are remarkably adaptable to the forces they are exposed to, but that if we overload them in any one way we can run into trouble. Hence, by varying shoes, we constantly expose our feet and legs to varying force application, avoid repeatedly over-stressing them in a single way, and make them stronger overall.

What struck me when I listened to this is that Lam’s approach and thought process is remarkably similar to my own. One of the topics that I teach about each year in my Human Anatomy and Physiology course is a concept known as Wolff’s Law. Basically, Wolff’s Law states that our bones remodel to better withstand the forces that we habitually expose them to. Most people (including my students when I tell them this) don’t tend to think of bones as dynamic, changing structures. Our typical thought is that a bone is a bone, just a hard white thing inside our flesh that helps to hold our body together, protect us, and prevent us from collapsing into a pile of mush on the floor. The reality, however, is much more complex.

The Adaptable Human Body

Our bones are quite remarkable in that they are capable of going through a process known as remodeling. What this means essentially is that our bones can change shape. We have little cells called osteoclasts and osteoblasts that can break down old and build up new bone (respectively), and they do a very good job of it. When we stress a particular spot on a bone repeatedly, it can begin to develop micro damage – think of micro damage as tiny cracks that weaken a bone in that spot. The remodeling process repairs that damage, and ultimately will make the bone stronger and better able to withstand that stress. The catch is that it has to be allowed to happen. Remodeling takes time, and the damaged spot can actually get a bit weaker (as damaged bone is removed) before it is repaired and becomes stronger. If we repeatedly stress a bone in the same way over and over without giving it a chance to rest and repair, micro damage accumulates and can lead to a stress fracture. If we continue to stress a bone that has already developed a stress fracture, you can imagine what will happen next – snap!

This same type of process applies to many soft tissue injuries as well, and muscles are a good example. When you go lift weights for the first time in a long time you get incredibly sore for the next few days (this is called delayed onset muscle soreness or DOMS). What has happened is that you have damaged your muscles on a microscopic level, and as they repair themselves they become stronger and larger. This is the fundamental process by which we are able to increase strength through resistance training. However, if you decide to start working out and you do the same routine every day for a week or two, you’re asking for trouble. We could apply this same logic to an extent to ligaments and tendons as well. The body is amazingly good at adapting, we just need to allow it to do so.

What causes repetitive overuse injuries?

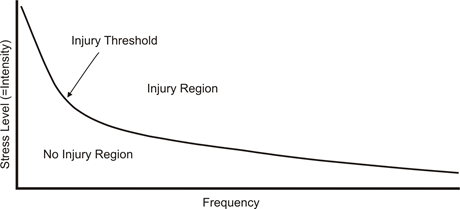

Repetitive overuse injuries are perhaps the most common type of injury experienced by distance runners (including things like plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, shin splints, stress fractures, etc.). Thus, in the context of what I have discussed above, it’s critical to address the question of why these overuse injuries happen. The answer to this is pretty much summed up by the quote I chose to open this post. Repetitive use injuries occur when repeated stresses are placed upon a structure, none of which individually causes acute damage, but the sum of which leads to a progressive degeneration of that structure. In simple terms, if you pound on a bone too frequently without rest, it’s eventually going to break. If you overstretch a ligament repeatedly, it’s eventually going to get sore and possibly tear. I think you get the picture. A helpful way to think of this is demonstrated by the graph below, adapted from Hreljac (2004).

The above graph looks at training and injury likelihood as a balance of intensity and frequency. High intensity workouts (e.g., hard speedwork, long runs) are more taxing on the body, thus if they are done frequently your training will exceed the injury threshold (the curved black line) and you’re asking for a problem. However, if your workout is low intensity (e.g., a short recovery run at a slow pace), you can do that workout frequently and not likely get hurt (i.e., you will remain in the “no injury” region).

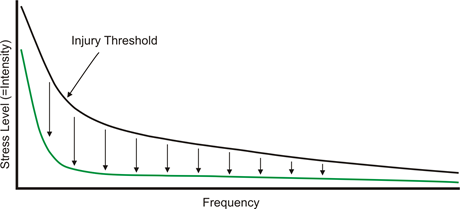

The thing to keep in mind in the above graph is that the exact shape and height of the curve will likely vary from person to person (some people are simply more injury prone than others, some can tolerate hard workouts better than others), from time to time within a single individual (e.g., with degree of overall fatigue), on different running surfaces (dirt vs. asphalt vs. concrete), and even in different pairs of shoes. As an example of the latter, when a person used to wearing cushioned, heel lifted shoes goes for their first run in a pair of Vibram Fivefingers (see picture above), which lack a heel lift and are minimally cushioned, the entire injury threshold curve probably shifts downward (see green line in graph below). Thus, in beginning Vibram runners, even low intensity runs should not be done frequently at the start, and high intensity runs can cause problems immediately (i.e., you don’t want your first Vibram run to be an all out 5K race).

The thing to keep in mind in the above graph is that the exact shape and height of the curve will likely vary from person to person (some people are simply more injury prone than others, some can tolerate hard workouts better than others), from time to time within a single individual (e.g., with degree of overall fatigue), on different running surfaces (dirt vs. asphalt vs. concrete), and even in different pairs of shoes. As an example of the latter, when a person used to wearing cushioned, heel lifted shoes goes for their first run in a pair of Vibram Fivefingers (see picture above), which lack a heel lift and are minimally cushioned, the entire injury threshold curve probably shifts downward (see green line in graph below). Thus, in beginning Vibram runners, even low intensity runs should not be done frequently at the start, and high intensity runs can cause problems immediately (i.e., you don’t want your first Vibram run to be an all out 5K race).

After the first Vibram run is complete, I suspect that muscular soreness in places like the calves will lower the injury threshold even further prior to the next run, and this is why running too much too soon (TMTS) is a deadly combination when adapting to a shoe like the Fivefingers. Adapting to Fivefingers requires a very low intensity initial approach with lots of rest – to do otherwise dramatically increases your likelihood of injury. The metatarsals and the muscles of the feet and legs need time to adapt to the new forces that they are experiencing when running in Vibrams, and metatarsal stress fractures are a seemingly common occurrence among new Vibram runners who do not heed advice about transitioning gradually. The positive is that as the adaptation process proceeds, the green line will ideally start to rise back upward, and along with it the risk of injury will decline.

I’ll finish off this section with a second quote from the paper that was the source of the opening quote – it sums up very well the points that I have tried to make so far:

“It is logical to assume that the musculoskeletal system of runners could recover and repair itself rapidly enough from relatively low levels of impact forces, but some threshold level of impact force, repeated for some threshold level of repetitions would result in injury. It is also likely that a runner who has maintained a training program in which these threshold levels have not been exceeded would have the various related structures remodeled in such a manner as to become more resistant to injury.” Hreljac et al. (2000) in Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise

How do we avoid repetitive overuse injuries?

Two things are critical to helping a runner minimize the risk of suffering a repetitive overuse injury, and the first is rest. If you begin exposing a bone in the body to a new form of stress, such as greater impact on the metatarsal heads or bending torques on the metatarsal shafts when you decide to start running barefoot or in a minimalist shoe (particularly if you adopt a forefoot strike, and even moreso if you try to run up on your toes and not let the heel come down after initial contact on the forefoot is made), you need to allow the bones time to remodel to better withstand those new stresses. My suspicion is that failure to do so is the major cause of metatarsal stress fractures in new barefoot and minimalist runners. Among newer minimalist runners, TMTS is the first thing I and other minimalist runners suspect as the causative agent among people who develop these types of injuries. People get overly exuberant about trying a new thing, buy a pair of Vibram Fivefingers or other minimalist shoe and run every day for a week in them, and rapidly start to break down. It’s a recipe for disaster. If, however, you start out slow, do short runs once a week or so in the new style, and allow plenty of rest, you provide a dose of the new stress that the body can manage. Then, following Wolff’s Law, the bones in the foot are able to remodel to better withstand those stresses on future runs. The muscles and ligaments also likely strengthen, helping in the support process, and further minimizing fracture risk. Rest is critical to this process, and following this approach I have thankfully been able to avoid any serious injury as I have extended the distance of my Vibram runs (I have now run as long as 15 miles in my Vibram Bikilas on a single run).

The above approach is also the one advocated by many barefoot runners. They will often recommend ditching shoes completely, and allowing the body time to work it’s way into the new style slowly. The idea is that by going barefoot, your feet and legs will tell you when they have had enough on a given run, and you need to listen to your body and provide yourself with the appropriate amount of rest needed for recovery. It’s a seemingly effective approach that several of my barefooting friends have used with good results, but full time barefooting is not an approach I have tried, so I’ll leave it at that for now.

I should add that the above approach doesn’t necessarily apply to just going minimalist or barefoot. Any time you change shoes you are likely exposing you body to a slightly different set of forces, and for this reason even this type of transition should be made slowly. Work a new shoe into your runs in moderation, and don’t use it for a 20 miler on your first time out (trust me, I’ve done it, and it wasn’t pretty).

Another potentially effective approach to avoiding repetitive overuse injury is the one Lam discussed in the podcast mentioned above, and the one that I currently practice myself – rotating shoes. I’m lucky in that in writing this blog, I have access to a lot of shoes, and I rotate my footwear on an almost daily basis. My thinking is that each shoe will stress my body in a slightly different way given it’s structural makeup (things like heel height, cushioning thickness, etc.), and thus rotating shoes might help me to avoid developing repetitive overuse issues. I have no real way of knowing for sure that this happens, but my hunch is that by moving stress points around as I vary footwear, my legs and feet become stronger and more injury resistant all around. It seems to have worked for me so far, and I’ll outline a personal example below that seem to support this logic.

Although I have not suffered a serious injury since I became a higher mileage runner, I have had my share of more minor aches and pains (I doubt there is any way to truly avoid these). Often, I find that these occur when I stick with one particular shoe for an extended time, or build mileage up too quickly on a shoe that my body has not adapted to. In almost every case, I have found that by consciously choosing a shoe on subsequent runs that has a slightly different structural makeup, I can continue running and the pain goes away. In essence, what I think is happening is that I am resting the strained spot by using a shoe that concentrates stresses in a different area.

As an example, this past summer I ran a lot more than I ever used to in the Vibram Fivefingers. As mentioned above, I had built my mileage up to a long run of 15 in the Vibram Bikilas with no major issues. However, the long run mileage increase was rather quick, which had me paying acute attention to any feelings of discomfort. About a month and a half ago I wore my Vibram KSO’s for a hard 5 miler – the next day I felt some discomfort under my second metatarsal head on my right foot, and an ache in my heel on the left side, which immediately had me fearing plantar fasciitis. Both of these worried me greatly. My response was to follow the above logic and take some time off – not from running, but from the Vibrams. I wound up running my best long run of the year in Nike Free Run+’s just two days later (they have a bit more of a heel buildup and a lot more cushion), and after a week of running in the Nike’s and Saucony Kinvara the pain was gone. I didn’t lose out on any mileage in prep for my Fall marathons. I managed my first BQ in my first Fall marathon, to which I give leg strength gained from the Vibram running a lot of credit, and am now back to running in Vibrams without much issue (except sore calves once again – amazing how quickly they revert).

Essentially, what I did in the above example was to listen to my body. Neither of the pains I felt were serious, but I wasn’t going to push it because I’m aware of what either of these pains could have become if I had continued to plow through with my Vibram runs (metatarsal stress fracture and plantar fasciitis). Not wanting to risk being sidelined for weeks or months, I made the choice to switch shoes, and it worked like a charm.

So what should you take from all of this? Basically, my feeling is that risk of repetitive use injuries can be minimized, though probably never fully eliminated, if you take a wise approach to your training. The following tips are the ones that I try to use myself – no guarantee that they will work for everyone, but it’s my best attempt at summarizing my current thinking on the issue:

1. Don’t do high intensity workouts frequently unless you know your body can handle it.

2. Don’t switch to a new shoe cold turkey and proceed with normal training loads. This is particularly true of the shoe you are transitioning to is structurally different than your previous shoe in a significant way (e.g., lower heel, different level of cushioning, etc.). It’s best to work a new shoe into your rotation gradually.

3. Rotate shoes if you can. Use a flat for speedwork (I like spikeless XC flats), a more cushioned shoe for long distance work (Most of my long runs for my previous marathon training cycle were in the Saucony Kinvara and Nike Free Run+), and a shoe like a Vibram for form work and strengthening. Mix it up a bit, break the cycle of repetitive stress from time to time, and hopefully you will avoid over-taxing any one spot on your body. If something feels wrong after several runs in a shoe, try something else and see if it gets better.

4. If you can’t afford to rotate shoes, do some running on trails. I find that trail running is a completely different type of workout than road running, and part of it is that you are running over uneven terrain. This helps to keep your legs working in different ways, breaks the repetitive cycle so typical of road running, and I suspect makes your legs overall stronger. Trails are also typically softer and more forgiving than asphalt and concrete, which helps to mix things up as well.

5. Try to avoid running the same route over the same distance at the same pace on every run. Again, mix things up, change speeds, run hills, etc. The more repetitive your workouts are, the more repetitive the stresses you experience are, the more likely you are to break down (unless, perhaps, your workouts are very low intensity).

6. Above all else, take time to rest when you feel you need it. Your body is good at telling you something is wrong, so don’t let a slight ache turn into a major problem. You’re far better off taking a few days off than risking a severe injury and being sidelined for a month or two.

Thanks for the great perspectives on running injuries Pete. A lot of your recommendations are what I currently practice and I credit to helping me stay relatively healthy for the last 1.5+ years. One thing I want to add is that by doing core and strength exercises, you can increase your body’s ability to handle higher volumes and intensities. But like everything, you need to introduce it gradually. Ultimately, you’ll be a better runner. Cheers!

Great point on strengthening exercise – thanks Fitz!

Agree with this 100%! So much so, that I have seen Fitz’s site and will be in tough with him soon. My ongoing ITBS is a direct result of not strength training. Just started running in Kinvaras and have looked at Vibrams, but fear they would be TMTS, especially with my ITBS. Will rotate the Kinvaras and my clunky Asics 2150s for now.

Great post, Peter! This leads me to wonder if part of the problem I had in the summer trying to adapt to full-time barefoot running was the fact that my footwear (i.e. my feet) never changed. (Not sure what to make of that. Just throwing it out there.)

One thing I have begun to do in recent months (for reasons that just seemed logical to me) is to vary my shoes based on how my feet/legs are feeling. For example, on days that one or both of my Achilles tendons feel a little tender, I will run in New Balance MT100s, which have more of a heel lift than my other current shoes (Mizuno Wave Uni and Newton Sir Isaac).

Excellent post, Peter! I fully agree with your conclusions and this is something I was thinking about. Now things are clearer in my mind. Another aspect that you can change if you feel discomfort, apart from the shoes, is to run on a treadmill. The muscles and tendons that you use are somehow different from the street experience. I did that this week. Last weekend I felt a discomfort at my knee and this week I ran on a treadmill and felt nothing.

Regards,

Sergio (Brazil)

corredorfeliz.blogspot.com

Excellent point about the treadmill – very different experience for sure.

great post! wish I read it before breaking in the new kicks =/

Great post… makes so much sense. I had read in the past that you switched shoes when something hurt so I did the same recently when my xc flats (and, yes, I admit it… a wee bit of unshod running) caused some foot pain. A week or so in my Mountain Masochists worked like a charm.

My only questions is this – Scientifically speaking, the frequency with which I can now purchase new running shoes guilt-free is directly correlated to… what? If I run 30mpw can I tell my hubby the new shoes are for medicinal purposes?! Insurance?!

Excellent question – perhaps we need to find a physician who can provide us

with a note. I could use one to explain this to my wife as well :)

Great read Pete,Was going to risk breaking in a new pair of Newton motions a couple of days before my upcoming marathon but had decided against it am glad now.

Great post! My only comments are:

1) While I fully agree with the logic of rotating amongst different shoes so-as to minimize the likelihood of a specific injury potentially triggered by a certain shoe’s stress-points, I’d urge caution to a runner unaccustomed to running in shoes with a minimal heel-to-toe drop following your example of doing speed-work in running flats. Such a runner doing high speed interval efforts in flats can quickly exacerbate problems for their Achilles tendon and calf (I’d recommend such a runner transition instead to flats through incorporating them into their recovery and easy runs);

2) Your suggestion that someone may not be able to afford to rotate amongst different types of running shoes is somewhat negated through rotated shoes lasting far longer (since it’s obviously miles versus time which ages them), and as there are substantial savings through not buying the latest hyped shoes.

Mark – your first point is basically what I was saying about running in

Vibrams, or adjusting to any new shoe. The second point is a good one, but I

get a lot of emails from people who can only afford to buy a single pair of

shoes on their budget – that’s where the comment was targeted.

Pete,

Great post. I’ve discussed rotating running shoes with fellow runners at my club. We reached a similar conclusion that rotating different models is beneficial as each model produces slightly different stresses. Of course, this is purely speculative as it is not based on any scientific evidence but it feels correct. The graphs are excellent (a picture paints a thousand words etc). Would you mind if I ‘borrowed’ them for an article in my club newsletter? I’ll give your blog a mention of course. Regards, John.

John,

Yes, feel free to use the images – I’m happy to help!

Another great post Pete. I’ve been chewing on this one for a while, will forward you a couple of journal citations to think on (just more to advance the argument). You’ve definitely done a good job of nailing down the arguments regarding repetitive tissue stress and how exceeding a given tissue’s (bone/tendon/muscle) tolerance to deformation creates injury.

Kent – I’d love to see any references you might have. This post has been in

my head for a long time, and the general topic of bone remodeling is

something I have been interested in since I took a skeletal tissue mechanics

class in grad school. I’m fascinated by this stuff.

Pete

If you are interested in the current theories on WHY injuries actually happen (impact forces do not seem to play a significant role!), check out some of Benno Nigg’s more recent studies–he’s done a lot since 2000 or so on “soft tissue vibrations” and how the lower extremities adjust to different conditions (shod, unshod, hard surface/midsole, soft surface/midsole). It’s a much more complicated picture that I ever imagined!

I have read some of Nigg’s stuff, although the vibration research is not

something I have looked into much as yet – thanks for the suggestion! I saw

his mention of the subject in the recent Runner’s World article on

minimalist shoes, but matching shoes to runners based on vibration

frequencies seems like a tough one to apply practically.

Regarding impact, Nigg seems to downplay impact forces, but others have

shown correlations between vertical impact loading rate and repetitive

stress injuries (e.g., Irene Davis and some others). It’s a very complicated

topic, and one that has many conflicting viewpoints that are supported by

some studies and not by others. Regardless, I doubt anyone would argue that

impact does not play a role in fractures that occur from switching to

quickly to highly minimalist shoes like the Vibram Fivefingers.

Pete

Great post, Pete. If any of your readers are interested in acupuncture for overuse injuries, you/they might enjoy this piece from AcuTake, on Achilles tendinitis in runners. link to acutakehealth.com…

I agree with switching shoes. I would also add that cross training/strength training is another way to even out the stresses caused by running. Mixing in some time on a bike or doing some leg extensions, etc. activates lesser used muscles thus balancing them with those heavily taxed by running.

Not sure if you posted on the topic, but what’s you opinion on stretching for the prevention of musculoskeletal injuries? I think they help me. Literature seems to say if they help do them, otherwise they’re not needed. And other literature hint at increased running economy with shorter tendon length (less flexibility), which I think I may have read somewhere where this also decreases injury risk…

I don’t know the literature on stretching very well, but from what I have

heard it sounds mixed. I think your take is about right – if you feel they

help, then do it, otherwise not necessary.

Pete

I’m debating getting some VFF Bikila’s as a new shoe (I’ve been using the NB MT10’s for the past three months or so), but I am coming off of an over-use injury (I pulled/strained something in my foot). Because of this I’m a bit hesitant to move toward any zero drop shoe, let alone Vibrams. Does anyone have any suggestions?

Thanks,

Bren

MT10 – are you referring to the Minimus Trail? I also have peroneal tendon

issues in some shoes, including the MT101. I actually find that shoes like

the Vibrams cause the fewest issues for my peroneals.

Pete

Sorry, should have been more clear, the Minimus Trail. I’ve put 130 miles (give or take) on them and had no problems until a short run the day after one of my longer workouts, so I’m pretty sure I just pushed a bit too hard. I’m just a bit worried about transitioning coming off of an overuse injury. Any thoughts on the best method for this aspect would be appreciated.

Bren

Slow and steady are the key things if you move into Vibrams.

Personally, I don’t use Vibrams as a full time shoe, but more as a

form work and strengthening shoe once or twice a week. I find rotating

among a few shoes to be of some benefit. If you go cold turkey into

Vibrams and don’t cut back to minimal mileage at first, it’s easy to

run into trouble.

Pete