One of the good and bad things about writing a growing running blog is that I get a lot of email. It’s good in that I love hearing from readers, bad in that I get so much that I have reached a point where I am simply unable to answer everything that comes in. Sometimes, however, I get a question that has broad relevance, and these emails can prompt blog posts. I received one such email yesterday from a runner, here is what he asked:

One of the good and bad things about writing a growing running blog is that I get a lot of email. It’s good in that I love hearing from readers, bad in that I get so much that I have reached a point where I am simply unable to answer everything that comes in. Sometimes, however, I get a question that has broad relevance, and these emails can prompt blog posts. I received one such email yesterday from a runner, here is what he asked:

I’m a serious runner who uses traditional running shoes such as Nike Air Pegasus and Vomeros for training and racing.

Recently I bought a pair of barefoot Nike Free 3.0 shoes which I am considering switching to but I’m a bit wary because I have a proprioceptive heel strike.

Would a minimalist shoe increase or decrease my injury rate if I’m slightly heel striking?

Questions like this one are challenging because the answer is not always simple. In most cases there is really no way to know because the shoes being asked about have not been put to the test in any form of trial, and every runner is a bit different. My advice is typically to ask why the runner is interested in changing. If their reason is valid (e.g., currently injured and want to try something different, curious and want to experiment), I generally point out that any change can potentially cause problems, and recommend that they approach any change carefully and gradually so as to let the body acclimate slowly to the new condition.

In this case though, there is actually some published data on how people fare when transitioning into the Nike Free 3.0. I thought I’d run through some of the evidence that is available in an attempt to answer this reader’s question.

Studies that Have Looked at Running in Nike Free Shoes

1. Ryan et al. found that 38% of runners who transitioned into the Nike Free 3.0 from a more traditional running shoe suffered an injury. It’s not clear what types of injuries they suffered or how serious they were, but the risk was significantly higher than for runners who transitioned into the Nike Pegasus (a shoe likely more similar to what they had been running in prior to the study).

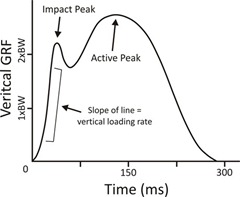

2. In another study, Willy et al. compared running biomechanics between heel striking runners without minimalist running experience in the Nike Pegasus and the Nike Free 3.0 (on a treadmill). They found that runners in the Nike Free 3.0 exhibited higher vertical impact peaks and higher vertical loading rates (and, surprisingly, more pronounced heel strikes with greater ankle dorsiflexion). Step length and step rate were not significantly different between the two groups. Differences did not change after 10 minutes of running in the shoes, so no short term adaptation to the more minimal footwear was observed. The researchers did not look at longer term adaptation to the shoes, and they did not provide advice on running form.

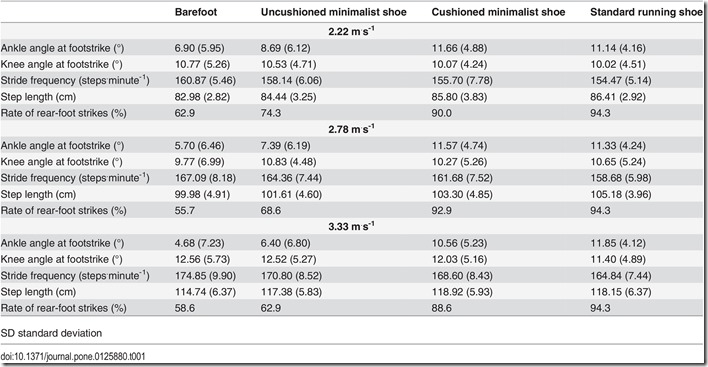

3. Bonacci et al. found that runners in the Nike Free 3.0 had reduced stride length and increased cadence compared to running in their standard conventionally cushioned running shoe. Reduction in stride length and an increase in cadence have been associated with reduced loading at the knee and the hip. However, the Free 3.0 did not alter their foot strike or most other parameters that were measured. When running barefoot, these same runners had a significantly less dorsiflexed ankle at contact (flatter foot strike) and significantly reduced midstance knee flexion compared to all shod conditions. A difference between this study and the Willy study mentioned above is that runners in the Bonnacci study were given 10 days to acclimate the the more minimal footwear and they ran overground versus on a treadmill. These factors could explain the contrasting findings for stride rate and stride length.

4. Potthast et al. found that individuals who exercised in Nike Free shoes experienced a 20% increase in toe flexor strength. In another abstract the same group reports that exercising in Nike Free shoes also increased ankle plantarflexor and dorsiflexor strength. It is important to point out that these studies were looking at general exercise effects, no specifically running.

What Does This Tell Us?

If you look at these results, we find that there may be some benefit to trying a shoe like the Nike Free from a foot strengthening standpoint (it’s likely that different shoes simply strengthen the body in different ways, maybe not that one is inherently better than another), and they may encourage a shorter, quicker stride with some amount of acclimation. The latter may lead to reduced loading of the knee/hip over the long term, but we don’t currently have data to support that.

However, we also see that impact loading can significantly increase initially for heel strikers in a moderately cushioned minimal shoe like the Nike Free 3.0. This is cause for concern, especially since Willy et al. report that “…the average vertical loading rates that we found during minimalist shoe running exceeded the values reported in runners with a history of tibial stress fractures by Milner et al. (78.97 bw/sec, ± 24.96).” Furthermore, there is some evidence that runners transitioning into a shoe like this are at higher risk of injury (over one-third of the runners that transitioned into the Free 3.0 in the Ryan study got hurt).

So at least for the Nike Free 3.0, there is probably an increased risk of injury, at least initially, when transitioning. Long term data are lacking. But, it’s also important to point out that 62% of runners who went into the Nike Free 3.0 in Ryan et al. did not get hurt, so it’s not the case that everyone who migrates into a shoe like this will suffer an injury. And, given that we don’t have a clear picture of the types of injuries suffered by the Free runners, it’s hard to know if continued heel striking and resulting increased impact loading might explain the increased injury risk.

One additional point is worth making. The Ryan study also looked at how migrating into an even more minimal shoe, the Vibram Fivefingers, affected injury rates. Though there were slightly more injuries in the Vibram group compared to those that stayed in conventional shoes, the difference was not significant. The only elevated risk was found for runners moving into the Nike Free. Interestingly, Willy et al. write the following in their discussion:

“Many runners use these transitional shoes as a way to adopt a barefoot-mimicking running technique, involving minimal plantarflexion and a mild forefoot strike pattern.(15) However, these results suggest that runners should be careful when transitioning to cushioned minimal shoes. While there may be a belief that one will automatically adopt a forefoot or midfoot strike pattern by wearing minimal shoes, both the Bonacci and the present study suggests otherwise. When using one of the vast array of minimal shoes with cushioning, additional gait retraining may be needed in order to train one to land with a midfoot or mild forefoot strike pattern.”

They also write:

When taking the Squadrone, Bonacci and current studies together, the following points can be made. In order to see a change in footstrike pattern that simulates barefoot running, the shoes may need to be as minimal as possible.

My own research suggests that more extreme minimal shoes do seem to result in foot strike patterns that differ from those of traditionally shod runners, but almost 50% do still heel strike and the patterns remain significantly different from those of truly barefoot runners.

What’s more, though Ryan et al. did not find a significantly elevated risk of injury in Vibram runners, there is evidence that transitioning into such shoes stresses the metatarsal bones of the foot. This could lead to bone strengthening if stress is applied in a gradual fashion and remodeling occurs, but it could also lead to stress fractures if bone damage exceeds the ability of the tissue to repair and strengthen itself. This risk must be taken into account and a gradual approach is warranted if we are to recommend a minimally cushioned shoe as a method to induce form change.

So getting back to my reader specifically, what do I suggest?

First, the phrase “proprioreceptive heel striker” suggests that he has a mild heel strike. There is some evidence that heel strikes come in different forms. Some heel “contacters” tend to load under the heel, others more under the midfoot, and this may influence impact and related variables. Risk for a mild heel striker may not be as high as in a more pronounced heel striker in a more minimally cushioned shoe. But I am only speculating here, and I cannot confirm the exact nature of a reader’s foot strike via email. So I default back to saying the following:

There is some risk in making any kind of change in your training. There is evidence suggesting increased risk of injuries when transitioning from a traditional to a moderately cushioned minimal shoe like the Nike Free 3.0, but that does not mean that everyone making this transition will get hurt. The best advice I can give is to be aware of your form, avoid hard heel striking in a minimal shoe, and introduce any shoe that differs significantly from what you currently wear gradually. Maybe wear it only once or twice a week for short, easy runs for the first few months. Since you are a serious runner who trains hard, I do not recommend going into a shoe like the Free 3.0 all at once. If all goes well initially, then slowly increase mileage, but recognize that there is really no reason why you must go fully over to a more minimal shoe. In fact there may be some benefit to rotating shoes of different construction. Whatever you decide, listen to your body, back off if you feel any pain, and be careful.

‘be aware of your form, avoid hard heel striking in a minimal shoe’. The trouble with this advice, Pete, is that nobody chooses to run with bad form, so they’re doing it out of ignorance/bad habbits etc, which usually means they’re unaware of what they’re doing wrong or how to change it.

I’m not a golfer, so it would be a bit like someone saying to me ‘be aware of your poor swing’.

I don’t disagree at all, and I don’t think most people have any idea how they contact the ground when they run unless they are very diligent about observing shoe wear patterns, and even those at times can be misleading. I’ve had a number of gait analysis clients tell me they have been working on midfoot striking only to have video reveal that they are still pounding their heels big time. I do think that a more minimal shoe will modify form over time in some ways, even if it doesn’t result in a change in foot strike from one category to another. For example, I have video of a lot of heel striking Vibram runners, but it’s typically a much less pronounced heel strike than I see in more conventionally shod runners. I have seen other runners who almost bottom out the heel cushioning of a conventional running shoe so there has to be a ton of impact going on. I think we need to be much more aware of variation in the category we call “heel strike.”

You’re a gait coach, so clearly you have a bias in thinking that coaching is warranted. Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t. I think it’s a reasonable suggestion, but as someone who does gait analysis I also share a bias. I try to be objective and not self-serving, and prefer that until we have strong evidence showing that form coaching in conjunction with a shoe transition reduces risk of injury I hesitate to make a blanket recommendation.

I have always been a mid foot strider, but after coming back from a snapped lateral meniscus two and a half years ago, I slowly transitioned to newtons first, then saucony’s and altras. I went thru some back pains, calf pains, ankle pains, and foot pains, but generally held up enough to fully convert. Once converted though, I have found that concentrating on form as much as possible and adding lots of single leg squats and calf raises on gym days has allowed me to finally run longer and stronger even after 39 years of running. In retrospect, I think it was clearly worth it and will hopefully give me a few more healthy years….

Hello,

The obvious question is: what does one need to do, to change the heel strike to a “better” mid foot or forefoot strike.

I have read somewhere that trying consciously to land on your forefoot, i.e. plantar flexing the foot, is one of the worst things that a runner can do.

Which leaves us with:

1) Running barefoot / with very minimalist shoes, in order to feel at least with what are of your foot you are striking.

2) The usual drills

What would you recommend?

Take care

Jurgen

I don’t necessarily think people need to stop heel striking. There is no strong evidence to suggest heel striking increases injury risk or reduces performance, or that midfoot or forefoot is better. In fact, most every study that has looked has found no significant difference in injury risk or efficiency between the various foot strike types. I am for the most part a mild heel striker myself depending on the shoes I’m wearing, and am fine with that. As I go more minimal I shift further forward.

Probably the best we can say is that different foot strikes stress the body in different ways and we can use modifications if our goal is to offload a particular tissue. For example, when new runners in my Couch to 5K group suffer from anterior shin splints, I may suggest moderating a heel strike to reduce stress to the tibialis anterior. I had another woman this Spring who was having calf/Achilles issue and was a very pronounced forefoot striker. I actually suggested she might want to run midfoot or even with a slight heel strike.

The big question to me is whether there is a distinction between the various types of heel strike that can be observed. I see people with extreme ankle dorsiflexion who smash the heck out of the heel cushion in their shoes and can’t help but think that it is inefficient and potentially injurious, but I also have no real data to support this belief. Science has not weighed in on whether some heel strikes are better or worse than others, though we do know that various kinds of heel strikes can be distinguished via force measurements.

If your goal is to modify foot strike, practicing barefoot running can be a great approach, but I think must be done gradually to minimize risk to the foot bones and ankle plantarflexors and perhaps the Achilles tendon. My worry with forcing a forefoot strike is that it results in an exaggerated forefoot strike that put excessive stress on the foot bones and ankle musculature. I prefer to use cues to relax the ankle/let the foot dangle and aim for a flat landing or very slightly to the forefoot or heel. Track speedwork or strides in racing flats is another good way to work on form. Also, simply shortening up stride and increasing cadence may lead to changes in ankle angle at contact even if it does not result in a change in foot strike pattern.

Ultimately, the biggest issue is to only attempt change if there is a good reason to do so. If you are running injury free and meeting your running goals/needs it is probably best to not mess with success.

Yeah, actually focussing on foot ‘strike’ is a bad idea. Many who try to land on their forefoot end up plantarflexing and still overstriding, which as Pete’s pointed out just gives you a different set of problems. Equally, many who try to forefoot strike, do so without letting the heel kiss the ground afterwards to release the calf/achilles and utilise ther body’s boimechanical spring. This ends up a bit like running on your toes.

If you work at dropping the foot down to land close to under your centre of mass you will land nice and softly and safely -it’s very very likely you will land on your forefoot in doing so. If you’re wearing wedged running shoes at the time it’s possible you will have a slight heel strike, but that’s OK.

Shorter strides, quicker cadence is a good self help cue.

I guess when you change shoe lowering the intensity of your workouts a bit and then build it up might be a good idea. Might be a bit of a ego hit but i guess that is much better than getting an injury. Being extra careful about form is always a good idea.

I think the k the ego is a big part of the problem for a lot of runners. Mentality is often that I’m a strong runner and can handle a change no problem, but sometimes that approach doesn’t work too well, especially if you do a lot of miles and a lot of speed. I learned this after my first few runs in Vibrams – had pain on the top of my feet from doing too much too soon and was wise enough to put them away for a few weeks and start back really gradually. Had no issues when I used the more gradual approach. The difficulty is knowing individual tolerance and adaptation speed – some people can probably transition very quickly, some may never be able to go fully minimal.

This article is really what i was looking for.

I allway runned with solid and supportive shoe, but i´m willing to try a slow adaptation to minimal shoe for small (and faster) runs to improve my heel strike.

Is there another brands/shoes besides Nike Free (that is way to expensive in my country) that you recomend for a tryout adaptation?

Thanks for another interesting article. A question though, “If their reason is valid”? Just wondering what would be a invalid reason? I changed to bare foot because I became tired of buying shoes every 4 months or so. I transitioned over several months with very small increments in distance and time and ran on hard surfaces only.

I think your question is worthy of an entire post! But in short, an invalid reason would be for someone who is running injury free and getting what they want from the sport to change because someone scared them into making the change or presented them with unrealistic potential outcomes from making a change. For example, they heard or read somewhere that forefoot striking or minimal shoes will prevent them from getting injured or will make them run faster, so they decide to change what has been working for them. A change when everything is going well could just as easily trigger an injury as prevent a future injury.

I just recently transitioned from The Nike Air to the Nike 3.0 so far so good I usually have knee no matter what as I have a pretty good stride.